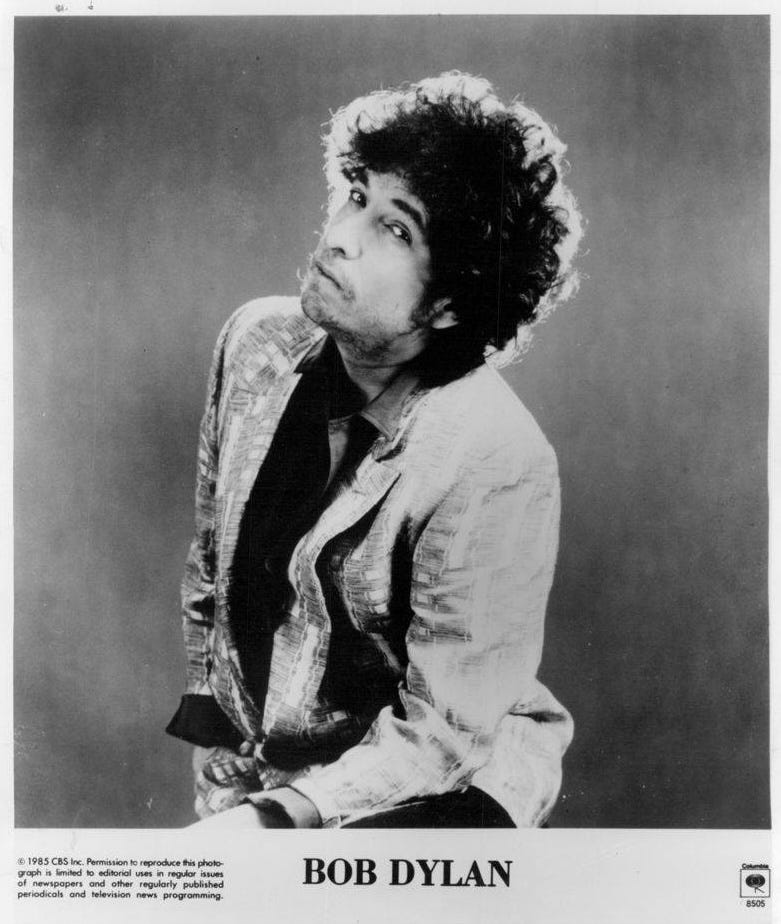

Guitarist Ira Ingber Recalls 1980s Rehearsals and Sessions with Bob Dylan

The Empire Burlesque Interviews #1

Flagging Down the Double E’s is an email newsletter exploring Bob Dylan concerts throughout history. Some installments are free, some are for paid subscribers only. Sign up here:

For the first part of our weeklong look at Empire Burlesque on its 40th anniversary, I spoke to Ira Ingber, a veteran L.A. guitarist who worked with Lowell George, Van Dyke Parks, and J.D. Souther, among many others. Bob Dylan enlisted Ingber not just to play on Empire Burlesque, but to put together the entire backing band for the early sessions.

They first spent several weeks rehearsing at Dylan’s house with no specified goal—just like the Plugz had the year before—then entered the studio. Ingber ended up on “Something’s Burning, Baby” on Empire Burlesque, but the more acclaimed song got reworked for the next album: “Brownsville Girl” on Knocked Out Loaded. You can hear him on several Springtime in New York outtakes as well. Decades later, he returned to the Dylan world to play on Shadow Kingdom.

Here’s my conversation with Ira Ingber.

How did you get connected with Bob initially?

His manager at the time, a fellow named Gary Shafner, is an old friend of mine. Gary had been working with Bob for at that point almost 10 years. Gary asked me if I would want to put a band together to go and rehearse with Bob. It wasn’t to record.

So I went up to Bob’s place first, up at his house in Malibu. We got along fine, and he asked if I had some other people I could bring by. At that point, he already had Charlie Quintana playing drums. He wanted to know if I knew of a keyboard player and a bass player.

So I brought two friends, Vince [Melamed, keyboard player] being one of them, and Carl Sealove, a bass player friend of mine, joining up with Charlie to just play. There was no talk of recording at all.

Then pretty early on, Charlie had to leave. He was going on a tour or something. So then Don Heffington showed up, who I knew a little bit. Don was the drummer in Lone Justice. Bob was really very fond of that band. And that was the group—Don, Vince, Carl, and myself—that were the core band for those Cherokee [Studio] sessions.

Tell me more about that first meeting, before you brought the band.

It was the first time we’d ever met. He handed me this song list, all of his songs, that were typed on onion skin paper. I’ll never forget it. He probably typed it himself. He said, “Do you know any of these?” I said, “Yeah, I do.” So we started playing his songs.

You mean old songs, songs that had already been released?

Yeah, his song list at that point. I was and still am a huge fan, so I knew just about everything. We started playing and he seemed happy.

This is just the two of you?

Just the two of us. The intimidation factor, of course, is built into something like that. I realized, much to my great fortune, that the only way to relate to this guy was to relate to him as a musician, not as this legend. And it served me well over the years.

Fortunately, I’d been around other well-known musicians at that point. I had done sessions with Frank Sinatra, which was chillingly frightening. I was 24 at the time. So by the time I got to Bob, it wasn’t that I wasn’t initially intimidated by him. I was. But within a few minutes, the survival instinct kicked in, and I realized that the way to successfully work with this guy was to work as a musician and not as an adoring fanboy. Because I’ve seen other people fall into the latter, and he eats them alive.

I’m from Minnesota also. As a matter of fact, we’re distantly related through marriage. So there’s a familiarity that I think came with my coming into his sphere. “Oh, he’s another guy from Minnesota.” It got off to a good start for the two of us. That repeated itself later on during the Shadow Kingdom stuff.

Too bad a tape wasn’t running. I’d love to hear that rehearsal, doing the old songs with just two guitars.

It was absolutely great. The great moments with Bob, and I’m sure every other musician of the thousands who played with him would probably say the same thing—when you’re alone playing with him, or in a very small ensemble, it really is magic. Because, besides the fact that he’s so good, there’s the intensity of the situation. There’s a gravity to this thing, and it inspires you to be your best. And it’s not just because it’s Bob. It’s that his focus is so intense, and his intention is a thousand percent in the moment.

He’s the most in-the-moment person I’ve ever met in my life. There’s only right now with him. And in those moments of making music, things don’t get better than that. You have the present moment, being very focused, and it’s contagious.

A perfect example of what I’m saying was the recording of “Brownsville Girl.” It was four of us plus Bob. For those 12 minutes, we held the attention. We were all really on the same wavelength in a really beautiful ballet.

Again, when we rehearsed at his house, we didn’t know we would be recording. It was about two or three weeks of rehearsing going up there a few times a week. Then I got the call, I think from Gary, saying, “Can you come to Cherokee tomorrow at 2 o’clock?” “What’s going on?” “Bob wants to record some stuff.”

With all these rehearsals, are you starting to work out the songs you’ll end up recording?

Yes. “Brownsville Girl” being a good example. We started playing that song in rehearsal. He didn’t tell us what it was.

We rehearsed in one of the houses on the property. He had a PA set up, and we were playing really loud, but he wouldn’t sing into the PA. He sang into our ears. He would walk over to me and sing to me or walk over to Vince.

Literally into your ear?

Yeah. He would just stand next to me and sing. Not into the microphone that was set up for him. Which we found kind of odd—but great. You know, we’re playing “Highway 61,” and he’s singing it to me. What’s better than that?

So you all are playing a mix of new and old things? “Brownsville Girl” and “Highway 61.”

He had a bunch of cassettes, as I recall. People were sending him other people’s songs to check out. So we’d learn this one or that one. He’d go, “I like this,” “I don’t like that.” You know, he was in a very fallow period at that point, and I think really seeking to find some relevance. This is the '80s, and he’s in his early 40s at that point. The era had really passed him by in many respects. Music was changing.

He was looking at ways of somehow putting his toes in the water for what was obviously this quickly changing musical landscape. He was very aware of it. This was early MIDI and synths coming in.

I had been recording at a studio called Skyline, which I later brought him to [for Knocked Out Loaded]. A dear friend of mine owned the studio, and he and I were recording as a duo. We were getting very modern and progressive and '80s—drum machines and all kinds of stuff. I remember I gave Bob a tape. He listened to it, and he said, “Oh, that stuff’s pretty wild” or something like that. It may have planted a seed in his mind about, that’s this new stuff that these guys are doing, which was completely foreign to him.

But to answer your question, the songs that we did in those rehearsals covered a range of things. “Brownsville Girl” at that point was called “Danville Girl.” By the time we got to Cherokee to record, we were saying, “Oh, yeah, I remember we played this one…”

So I would be willing to guess, during those rehearsals, his desire was to ultimately record that song among others, but he never told us, “Remember that song we rehearsed? Now we’re going to do that.” He just started playing it, and we were supposed to remember it.

I want to jump on one thing you said earlier, you connecting over your Minnesota roots.

I still have a large family in Minneapolis. My aunt, who married into the family, was distantly related to Bob’s mother. My aunt wanted to know what I was doing. I said, “I’m working with Bob Dylan.” She says, “Oh, Bobby!” She called him Bobby because she knew him as this young guy who came down from Hibbing to Minneapolis and befriended my aunt’s nephew on the other side.

I mentioned the actual person who kind of connected our families to Bob. He started. He said, “He saved my life!” I could tell he was like 15 years old again. He said, “I came down from up north and I didn’t know a soul. This guy took me in. Do you know him?” I said, “No, but Bob, there’s only 30 or 40,000 Jews in Minnesota. Of course we’re going to be related somehow.”

His line was, “And I didn’t know a single one.” Which of course is not true.

He went to Jewish summer camp!

He lies big. He lies almost for effect. I would occasionally catch him in it, and he would give me that sly grin.

But the Minnesota thing was also reinforced. My older brother recently passed. They were the same age, Bob and my brother. And they both had many similarities. Among others, they were both produced by Tom Wilson. My brother was in the Mothers of Invention, Frank Zappa’s first band, then later he had a band called the Fraternity of Man. He wrote the song “Don’t Bogart That Joint.” Tom Wilson produced that album. During the recording of the second Fraternity of Man album, I got to play on that record. And I mentioned that to Bob also that I worked with Tom. He was very impressed by that fact. Bob held Tom in the highest regard.

So the Minnesota part of it was, I think, a familiarity, for Bob especially. He doesn’t dwell on all the old-business stuff, but I think there was a level of comfort with me. I was okay. I was kind of on the inside.

We always got along really well, during the recordings of the '80s and then this later stuff. We just had a pretty clear sense of communication.

I’m repeating myself, but I think it bears repeating, the way to work with this guy was to relate as a musician. We had some kind of a misunderstanding, I don’t want to go into what it was, and I was on a phone call with him. I said something like, “Well, Bob, we do great work together, and it’s about the work.” And whatever the misunderstanding was completely cleared up when he said, “Yes, we do.” When I reminded Bob about the stuff that we did and do, he chilled out completely. Because, for him, everything’s about the work.

When we were rehearsing at his place prior to recording, he never took breaks. I would have to say, “Hey, Bob, can we take a break for some water?”—which he never offered. Nothing. Zero. No snacks. But it was in his house, so I was able to ask, “Can I make a cup of tea?” “Oh yeah, go ahead.”

He was absolutely driven. Then at 4 or 5 o’clock, whenever we ended, he would say, “Okay, can you guys come back tomorrow?” That’s the line he uses for everybody.

So let’s get to the sessions. Can you take me into Cherokee?

There was one session that was a defining moment for my relationship with Bob. We started recording, and, you know, we were all fairly well versed in studio etiquette at that point. You’re out there in the room, you come into the booth to listen and you make your notes and adjustments. There was no producer. Bob was doing it—it could have used a producer.

We had recorded a track, and Bob was putting a vocal on as an overdub. Bob’s one of the greatest singers in the world, I think. Unfortunately, especially in those days, he often picked the wrong take, from my perspective. Being his own producer didn’t help.

Anyway, he’s recording a vocal, and he really messed up the end of a line. The song finishes, and he says, “How was that?” I didn’t know who he was addressing. George Tutko was engineering the vocals. I said to George, “Are you going to tell him?” He said, “Nope, nope, nope.”

So I thought for a second. I thought, if I tell him, “Well, that was not very good,” that’s it for me. I could be out of here in a second. But I also realized that unless I was really honest with him, I wasn’t going to be much use to him. So my instincts prevailed. They pushed the talkback and I said, “I think you probably have a better ending.”

Silence. He doesn’t say anything. He gives me the long Dylan stare.

Uh oh.

Mostly because of his eyes. He has terrible vision. So a lot of that squinty stuff was not because he was giving you the look. He just couldn’t see you.

So silence, waiting. I’m thinking, “I’ll just pack up my guitars and leave.” Then he said, “Okay, let’s do it again.”

Dodged a bullet. From that moment, he almost invariably would ask me, “What do you think?”

More than dodged a bullet. It’s like you proved your worth.

Exactly. He realized I was someone he could trust. I wasn’t going to bullshit him, because there was nothing in it for me. Ultimately, he’d find me out. So it became a very healthy environment where I got to speak my mind pretty clearly with him.

You know, when we were recording the Shadow Kingdom stuff and we listened back, I said something he disagreed with. He said, “Why are you saying that?” I said, “Because that’s what I think.” He said, “Well, I think you’re probably wrong, but let’s try it again.” So he gave me a lot of latitude. Mostly, I think, because he had a sense that I was listening carefully and that I cared.

At those first Cherokee sessions, we’ve talked about “Danville”-slash-”Brownsville Girl.” Do you remember what other songs you recorded there?

“Something’s Burning” we did with live singers, Madelyn [Quebec] and Queen Esther [Marrow]. They had a horrible time because he never worked out any harmonies. They’re just trying to follow him in real time. That’s why the vocals are delayed. They’re trying to come up with parts in the moment, singing live with him, which is almost impossible to do. They did an amazing job.

They kind of run together with the next group of sessions, which happened in '86 at Skyline, the studio my friend owned. What happened was I got him to Skyline because he was really complaining that the drive from his house to Cherokee was really long. I said, “A really good friend of mine has a studio in Topanga,” which cut the time in half for him. He came up and loved it. And that’s where we ended up doing what turned out to be the bulk of Knocked Out Loaded.

Essentially, those two albums are the same album. You probably figured that out.

There’s much more mixing and crossover than you often get.

Yeah, they were all of a kind. Some things were started at Cherokee that were finished at Skyline, like “Brownsville Girl.”

So something like “Brownsville Girl,” when you’re recording it at Skyline the year after it doesn’t get used on Empire Burlesque, are you starting from scratch?

No, no, no. It was all overdubs. The basic tracks were Cherokee. They never changed.

So even though the title and the chorus changes, the music doesn’t need to.

He came up to us one day and said, “I have to call it ‘Brownsville Girl’ because there’s too many Danvilles. Too many states have a Danville in it.” Somebody said, “There’s too many Brownsvilles, Bob!” Come on.

Is Skyline all overdubs or changes to existing tracks, or are you doing live-in-the-room recording there as well?

There were live-in-the-room things, too. The live recordings at Skyline, in terms of what eventually made it to the albums, were probably little less than at Cherokee. There was a different band at Skyline. A bunch of people started showing up. Al Kooper showed up. Steve Madaio. Steve Douglas.

T Bone Burnett, who’d you also be on Shadow Kingdom with.

T Bone was a fixture there. He didn’t play a lot. He sat on the couch in the control room. He was mostly just there hanging out.

A sounding board for Dylan?

Not even. He was just sitting there absorbing.

I was looking through what has been notated from session tapes. There are all these unreleased covers you recorded. “Unchain My Heart.” “Without Love,” the Drifters song. “Lonely Avenue,” Doc Pomus. You mentioned him playing cassettes in your rehearsals. Was that the same sort of idea? He’s just playing other people’s songs?

That’s right.

I think the context of mid-’80s Bob, he was really fighting for relevance. Despite all the accolades, at that point of his recording career and live career, he was a little untethered. Everything was changing. That era that had given him the prominence that he achieved was gone, and I’m sure it wasn’t lost on him. So he was looking for anything to hold on to. If he’s going to record “Lonely Avenue”—“Well, I like the song, let’s record it.”

When we did Shadow Kingdom, of course, that was a different mandate. The idea was to reinterpret what I call the motherlode of his stuff. And we didn’t do any [covers]—well, I shouldn’t say that. We played about three-quarters of the way through Chuck Berry’s “School Days,” and then he said, “Oh, we’re not going to beat that thing, let’s not try.”

But the range of things that were brought up for possible recording during the '80s stuff was pretty vast. What’s going to stick to the wall is what ended up sticking to the wall.

You talk about him being sort of adrift, and you mentioned earlier him listening to some of the drum machine stuff you were doing. I’m sure it won’t be news to you that Empire Burlesque gets dinged in some quarters for, basically, the '80s-ness of the sound.

I really hated a lot of the sound of that record. I thought that Arthur [Baker] was chasing the au courant sound a little too closely. It has such a dated timestamp to me. For example, I listened to “Danville Girl” on the Springtime box set. That’s a great-sounding recording, because it’s unadorned, relatively. It doesn’t have all the extraneous and unnecessary reverb and horns and other stuff. It’s a lot more honest to me.

Again, I think it all comes back to the fact that Bob really didn’t have a clear vision of what he was going for when he made the initial recordings. So he turned it over to Arthur, because Arthur had some hits. Well, the result is that I don’t think that those records stand up.

I know a lot of people really like them. I think they like the songs. I think “Dark Eyes” is like one of the best songs he ever wrote, period, and it got buried in those records. To even be on an album with a song that great, I was thrilled. I figured, “Well, this is going to bring him back.” And of course, it had no effect whatsoever.

Did it kill you when Empire Burlesque comes out and “Brownsville Girl” is not on it?

Oh, absolutely. It seemed insane.

The mantra is, “You never know with Bob.” It’s always unpredictable. It’s always the unexpected. The notion somehow that there’s a straight line between A and B, you have to dispel very quickly when you’re around him. But yes I was disappointed. I was glad that it finally did come out on Knocked Out Loaded.

Again, those two albums to me are in this blender. I guess he figured he had enough material to put out two separate records. I think that they don’t hold up for many reasons, but one of which is the lack of overall vision. But that’s me. A lot of people seem to think they’re really good records.

I do like Empire Burlesque quite a bit. Knocked Out Loaded is more hit and miss. You got “Brownsville Girl” on one hand, but then you have “They Killed Him” with the children’s choir.

Look, Bob’s a reacher, you know? He experiments, and he doesn’t always succeed. And to his credit, when he succeeds, they’re grand.

I found some song titles that are things you supposedly recorded that have never come out. “Queen of Rock and Roll.” “Look Yonder.” “Gravity Song.” And then these are two from a one-off session you did in April '85. “Too Hot to Drive By”—love that title—and “As Time Passes By.” Any of those ring a bell?

Nothing. I want to give you a glimpse into Bob Dylan’s song title process. So we would record a song, and the engineer says, “What are we going to call it, Bob?” And he invariably would sit for a second and rub his chin or something. “Let’s call it ‘Everything I’ve Got Is Yours.’” “Okay.” He writes it down.

Then you look at the song, and there’s no reference to “Everything I’ve Got Is Yours” anywhere in the song. And you know this from all of the hundreds and hundreds of Bob’s songs that have titles that have no relationship to the rest. “It Takes a Train to Laugh”—I mean, really?

So those things you mentioned could have just been those one-off moments where he throws a title out that may or may not have any relationship to what eventually the song became. I do know that we recorded a lot of stuff. In the old days, the tape machine never stopped. There was always tape running. And I’m talking about we’re having lunch, and the tape machine is running.

Really?

Yes. Gary gave the order that the tape machines are always to be running. There were reels and reels and reels. Because Bob could very easily walk into the room, “Oh, I got this idea, I want to put it down right now,” And he didn’t want to ever have anything get missed.

Every night at the Cherokee sessions, Gary had to take the tapes out, put ‘em in his car, only to bring them back the next day, because of the piracy situation. He was the most-pirated guy in the world. The car was so loaded down, it was tilting back. Two inch tape weighs a lot. Every night the tapes went out; every morning they came back in.

So don’t leave the tapes in the studio overnight for God knows what to happen.

Tapes were never left. How those bootlegs of “Danville Girl” and a bunch of other ones got out before the albums came out, I will never know.

Did “Danville Girl” leak before Knocked Out Loaded?

Oh yeah. A bunch of stuff got leaked. It had to be someone who was staff at Cherokee who saw there was some gold there and somehow ran off dupes when we weren’t looking.

Thanks Ira! Stay tuned for the second half of our conversation, focused on the ‘Shadow Kingdom’ sessions, coming soon. In the meantime…

Fascinating read. You ask informed and thoughtful questions. Thanks for making this available to read for free!

Thanks so much Ray Pagget🌺

Enjoyed it a lot. Looking out to next part re.: Shadow Kingdom… Shared this💥🎶💥