Watching the Unreleased Supper Club Tapes

A rare viewing session one afternoon in Tulsa

Flagging Down the Double E’s is an email newsletter exploring Bob Dylan performances throughout history. Some installments are free, some are for paid subscribers only. Sign up here:

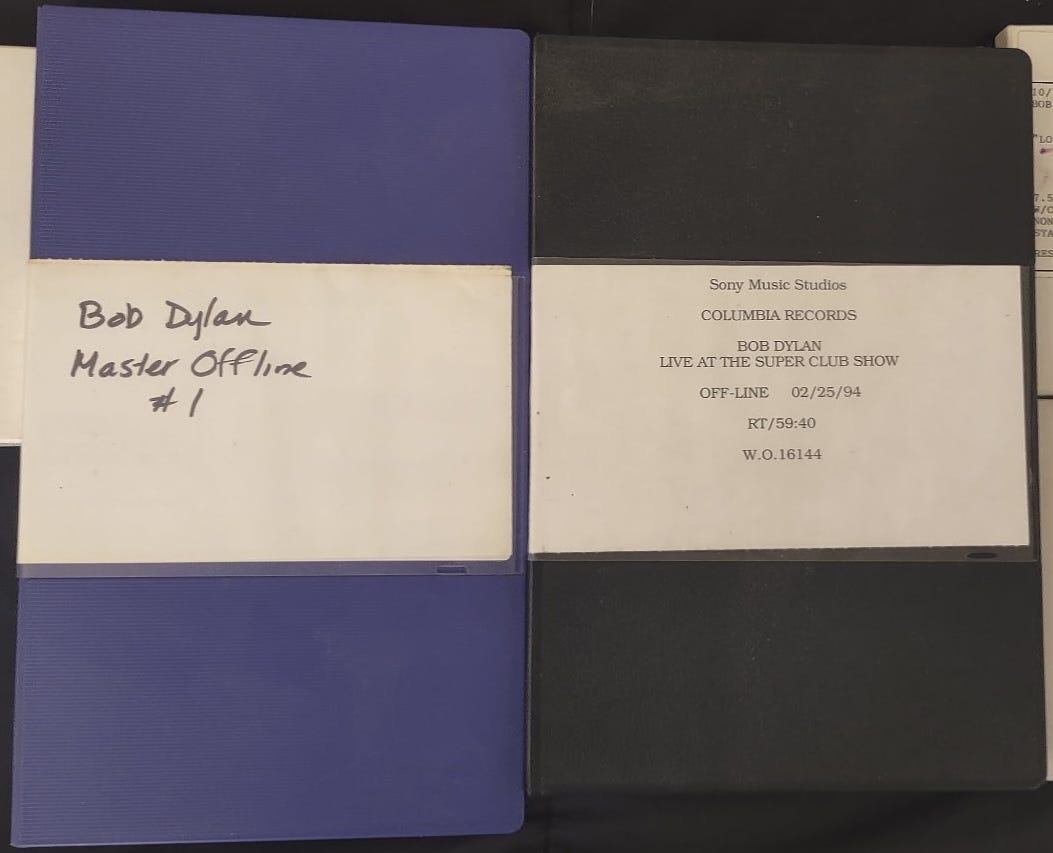

Back in July, I visited Tulsa to attend the World of Bob Dylan conference. While in town, I did a couple other things too. I visited the Archives and listened to some never-heard 1960s concert tapes. I interviewed a bunch of musicians at the Dylan Center’s “Going Electric” concert. And one thing I haven’t written about yet. I watched footage even the Archives won’t show you: The Supper Club tapes.

When I interviewed one of the archivists at the Bob Dylan Center’s opening in 2022, he told me the Supper Club footage was off-limits even to accredited researchers who can get access to almost everything else:

I was brainstorming what specific shows I was interested in. They’ve released a couple Supper Club videos over the years, on that CD-ROM they did back in the day. Do you have the full video from all of those shows?

Yes. There’s a body of material that’s been restricted though. Supper Club is part of that.

What does restricted mean?

It means that it won’t be accessible. You might see clips here and there in the Center, but as a whole, that material won’t be accessible until, I think that one is after Mr. Dylan’s passing.

Is that a legal thing?

It’s just what we inherited. There are things that they really wanted sealed off.

As a result, almost no one has seen this footage since Bob Dylan rejected it back in 1993. It’s one of the holy grails of Dylan collecting, some of the most sought-after film of his entire career.

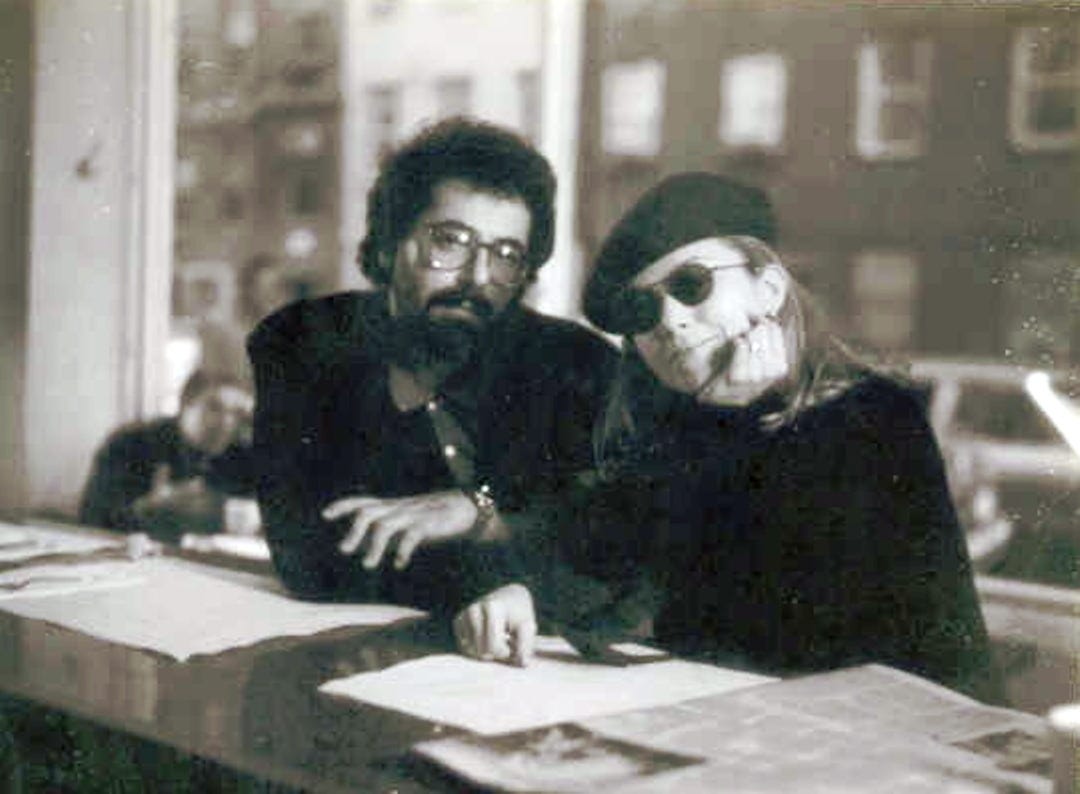

By happy coincidence, the director Michael B Borofsky lives in the area. Regular readers may remember, I interviewed Borofsky last year. He directed the Supper Club footage, along with a bunch of other Dylan stuff in the ’90s and many other artists. And he just happened to have some old VHS tapes gathering dust in a storage unit that he was willing to dig out for me…

The idea behind the four Supper Club shows was to, as Borofsky put it, “relaunch Bob.” At the end of 1993, Dylan’s career was coming out of a low ebb. He was being honored as if his best years were behind him: A Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award here, an all-star tribute concert there. His last two albums had been all covers—great albums, certainly, but albums that made people wonder if Dylan’s songwriting days were behind him. The Time Out of Mind comeback was still four years away. The Supper Club shows were intended to reposition Dylan as a still-vital artist, not some “remember the ’60s” relic.

To reboot Dylan, his team envisioned an intimate television program of Dylan performing acoustically for an adoring, jam-packed crowd. They booked New York’s tiny Supper Club for four unique shows, on November 16 and 17, two performances a night. They filmed all four, and there were plans to air the final product somewhere like HBO. But, after months of work, Dylan killed the project.

Why did Dylan kill the Supper Club video? You can find the full story in my interview with Borofsky, but a quick excerpt by way of summary:

At the end of the day, the reason why we’ve never seen it is because Bob never thought that the shows themselves were, to quote him, “in the pocket.” It wasn’t my fault. Bob told me this: “It’s not your fault. The band just wasn’t in the pocket.” I’m not a musician, so I always understood that to mean that, no matter how great those songs would’ve been to the fans, they just did not hold up. But they actually do hold up.

A short clip was released a couple years later—portions of “One Too Many Mornings” and “Queen Jane Approximately”—but with a rather large caveat: It was released using the extremely dated technology of a 1990s CD-ROM. Here’s how the footage was originally presented (credit @deadsoundapp):

Various fans have valiantly attempted to upscale and remaster these two clips, but that’s still the basic building block they’re working with: low-res CD-ROM video. In 2008, another song dropped, “Ring Them Bells,” on USA Today’s website promoting Tell Tale Signs. Better quality, but still a far cry from 4K, or even 720p. And, again, only one complete song and two partials rather than the full video.

Back to Tulsa. Borofsky still has videotapes of the Supper Club project, tapes that haven’t been played in over 30 years. He found a friend who still had a working VCR—not easy to do these days. On my final day in town, I headed over. We fretted about the machine eating these ancient VHS tapes (it didn’t) and had a brief scare when it turned out our host’s TV didn’t have the right port to connect an ancient VCR to. Luckily, the TV in his bedroom did. We all sat down for a viewing.

Borofsky himself hadn’t seen the Supper Club footage in three decades. We watched the finished product together—two versions of it, actually, with some different songs swapped in and out between the two tapes. While we watched, he added color commentary.

Sure enough, Borofsky was right. The Supper Club shows do hold up. Even on 30-year-old VHS tapes, it looks much, much better than the two circulating clips. Imagine how good it would look on the masters themselves.

So without further ado, let me tell you what I saw. And I do mean saw, rather than heard. Thankfully, we at least have excellent audio tapes of all four shows; what these shows sound like is no secret. So I’m going to focus on the holy grail part, which is what I saw in just under two hours of film footage I viewed. I realize seeing the videos yourselves would be a whole lot more exciting than just reading me describe them, but this is the best we can do for now.

Tape One

The first tape turns out to be, essentially, a cut of the final program (or what could have been the final program had it aired). It opens on a street scene outside the Supper Club. The line of people waiting to get in stretches down the block. They’re dressed in all the latest grunge fashions. This opening montage, Borofsky explains, was basically his sales pitch for HBO to buy the thing. Show the excitement, the long line, the fact that not everyone in that long line is a white-haired boomer. From the very first moments the goal is to present Dylan as fresh and exciting again.

The camera cuts to the club’s interior. The crew is setting up the stage, bringing in guitars. You see Dylan and his band backstage preparing to walk on. Instrumental music plays in the background. Borofsky says this is sound his cameras captured at rehearsals.

Most intriguing of all, this is all interspersed with footage from those same rehearsals. We see Dylan and the band at Sony Music Studios a few blocks away, dressed down, working out what they’re going to play. There’s no audio of this, alas—it’s still the instrumental music over top—and the shots fly by quickly, but it’s a tantalizing glimpse at what additional footage must exist. Borofsky teases a “Jack-A-Roe” rehearsal film clip that’s even better than the concert version. (Note: This is different from the rehearsal footage filmed at the Supper Club itself.)

Back to the Supper Club. We see fans entering, milling about, finding their seats. Waiters are serving drinks. You immediately get a sense of just how tiny this place is. The show’s about to start. We hear Al Santos recite the standard intro: “Ladies and gentlemen…Columbia recording artist…Bob Dylan.”

This tape begins with “Ragged and Dirty,” which opened three of the four concerts. The tape had timecodes at the bottom indicating what footage came from what show, but they moved too fast for me to track. Occasionally a song would feature footage from multiple shows combined, but generally it seemed true-to-life. The crowd is standing, bopping around. The camera moves a lot, from slow zooms in or out or pans from one band member to the next. There are a wonderful number of closeups—of Dylan of course, letting you see the subtle movements in his face as he sings, but also of the other musicians: Bucky Baxter’s resonator guitar with a glass slide, JJ Jackson fingerpicking his acoustic, Tony Garnier’s upright bass, Winston Watson going hard on the drums even with brushes. It’s intimate but fast-paced. Acoustic or not, this band is racing through the song, and the footage matches that vibe.

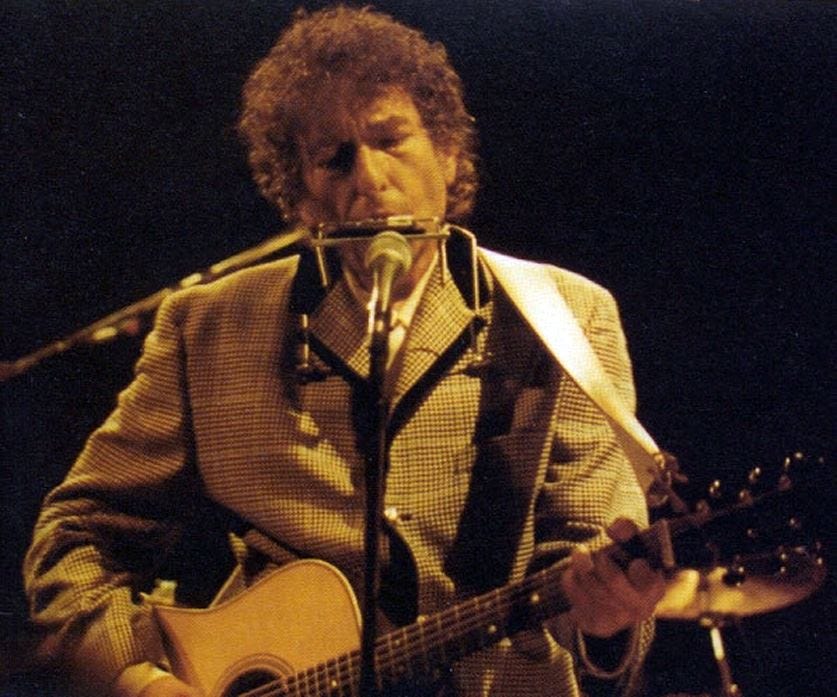

The folk covers continue with “Blood in My Eyes.” This never actually followed “Ragged and Dirty” at the shows; we see the first instance of songs being shuffled around for the film, which will happen often. I notice Dylan is wearing a harmonica rack. He doesn’t play it. This will become a trend: He wears the harmonica for many songs where he doesn’t touch it. There’s a wonderful shot of Bob and Tony making eye contact to close the song. This will be another trend: A lot of wonderful shots of Bob and Tony.

“Lay Lady Lay” follows. There’s a closeup shot of the band members’ cups onstage. “You see everything,” Borofsky explains. “That was the whole idea.” Some more distant shots show just how cramped and cluttered this tiny stage was. As Dylan solos, we watch him do his little leg wiggles. The camera slowly pans across the stage, hitting every band member in turn, landing on another closeup of Bob’s face. A closing crowd shot shows people applauding. There are a lot of baggy t-shirts and flannel.

It strikes me while watching “I Want You” how much better this looks than MTV Unplugged. I like that too, but it’s a brightly lit (hence Bob’s giant sunglasses) television studio. There’s so much less vibe than the Supper Club. The band here looks like Prohibition-era mobsters, and the young crowd is rowdy, with tons of heads and silhouettes popping into the frame. It’s a far cry from a sterile studio. Borofsky says they were aiming for a coffeehouse vibe, like watching Dylan in the years before Carnegie Hall, Royal Albert Hall, etc. Finally Dylan pulls up the ever-present harmonica, and the camera stays tight as we watch him play it. It’s one of the closest shots I’ve ever seen of him playing harmonica. I notice a blue chair placed onstage for somebody. I don’t think it ever gets used.

“Queen Jane Approximately” and “One Too Many Mornings” follow, both songs that were excerpted on that CD-ROM. I wasn’t in a position to A/B compare them to see if the edits are the same. These are the full songs though; not the shorter versions that circulate. There’s another shot of the cups, with gaffer tape around them. Borofsky recalls there was a person whose job was to wrap gaffer tape around the cups, to prevent the iris on the camera from overexposing on the cups’ bright white surface. “I’m remembering all this now as I’m watching these tapes!” he exclaims. “Ring Them Bells,” the other song we already have from the CD-ROM (albeit way lower-res), follows.

We’re a little over 33 minutes in as “Disease of Conceit” begins. The spooky atmosphere and dim lighting reminds me of Shadow Kingdom. This is filmed in color, of course, and with nary a mannequin in sight, but the vibe is similar. Hazy, like a dream. Borofsky says it was shot on Super 16mm film “with the subtle and delicate care that was meant to convey the point of view of every person at every table in the room.” There’s another harp-solo closeup, Bob grinning as he finishes, and a shot of Tony grabbing his bow for the big finish. The crowd goes crazy, yelling song requests. “Bobby!”

Another closeup on Dylan’s fingers playing a wonderful guitar intro to “Jim Jones.” This feels like being a fly on the wall at the Good As I Been to You sessions. I notice at this point I can’t even tell how many cameras are in play, because all the cameramen keep moving around. It feels like you get dozens of different angles across the various songs, even though Borofsky said there were only six or seven cameras total. There’s a long four-shot of Dylan, Garnier, Watson, and Jackson playing together that eventually zooms out to include Baxter too. Dylan makes a great bug-eyed face when he sings the words “Botany Bay” once near the end. It’s a shame he’s so video-averse, because he’s such a physically expressive singer. Dylan cues Watson, who grins, to finish. “Grinning” is a word I wrote down a lot. Bob and the band do a group-huddle to consult on something. Tony wipes his face with a towel.

Finally, the last song on tape one: “Forever Young.” I’m struck seeing this just how much less hits-centric this video is overall than MTV Unplugged, which was practically “I Love the ’60s” by comparison. This and “Lay Lady Lay” are really the only two giant everyone-will-know-them songs here. The timestamp indicates it’s after midnight now, but Dylan seems in no hurry. I notice a big sweat drop dangling from his nose. I remember noticing this elsewhere; was Dylan self-conscious about it? Surely if they can remove a coke booger from Neil Young’s nose in The Last Waltz, they can edit out an errant sweat droplet.

As the vocals end, Bob turns to Winston and the two groove together, Bob soloing on and on. It’s a great moment, just the two of them on screen, facing each other. Finally Dylan takes off his harp rack and fiddles with his collar and hair. He bows center stage, by himself. Suddenly it appears someone jumps up from the front row to kiss him on the lips! Did I see that right? Quite a way to end the program.

Tape Two

We eject the first tape and dig out the second. This turns out to be a “selects reel.” Meaning that, unlike the first tape which presented a full television program that could have aired as-is, this tape is just individual songs pulled from the four concerts. No opening montage, and long stretches of black between each song. It was likely done first. The lengthy black stretches—at one point we thought it was over until fast-forwarding eventually revealed the next song—are because the tape operator would let the tape roll while they were working.

Four of the eight songs here are the same as were on the first tape, and four are different. Between the two tapes I saw video of 14 different songs, of the 19 total performed across the four shows. But even of the four songs that were the same, Borofsky says these were different performances, from different shows.

At certain moments the cutting in this felt a little jumpier, like Borofsky described to me in our interview: “In those days, we thought that people’s attention span was short. I think the mistake I made was I cut it more like it was a rock and roll show, as opposed to it being sort of an auteur thing, which is the way I shot it.” Perhaps this tape shows some version of his own initial attempts, and the first tape we watched is the subsequent version he worked on side-by-side with Dylan, who wanted the cuts to slow down. The difference in editing style didn’t feel that dramatic though.

This tape again starts with “Ragged and Dirty.” I notice someone in the crowd holding flowers aloft. From there it segues to another folk cover, “Weeping Willow,” the only time he ever performed it and the first new song on tape two. Dylan’s expressive facial expressions are again a joy to behold, grinning as he solos, bopping his head. Jackson moves right next to him while they jam together.

“Ring Them Bells” follows. I noted down that this was apparently a different take than the first tape, as evidenced by the time codes on the bottom (this was the early show, first night). More closeups on Dylan as he solos, and then as he sings. “Closeups” really is the watchword on these tapes. So many times his face fills the entire frame. A far cry from how he treats any sort of camera today!

We see the crowd losing it when “Tight Connection to My Heart” begins, another song not on tape one. These are clearly not casual fans unfamiliar with rarely-played Empire Burlesque cuts. Bob feeds off the energy, dancing around the stage while he’s soloing. He’s going into what the Jokermen podcasters call “Wiggle Mode.” His eyebrows fly up, he’s grinning like a loon. I wrote down “This is nuts.” Tony’s smiling too.

Another “Disease of Conceit” follows. Between this and “Ring Them Bells,” I wish he’d done all of Oh Mercy live at the Supper Club. We see another great two-shot of Bob and Tony. I’m focused on Bob of course, but there are some great shots of Tony in these. You can hear his bass so well, and watch what he’s doing more closely than you ever could in an actual concert.

When “Delia” begins, it strikes me how much better the setlist represents this era in Dylan’s career than MTV Unplugged. Unplugged didn’t include any of the old-folk covers he’d just released two entire albums of, but the Supper Club films are chock full of them (there’s another up next). Despite him doing these incredibly old songs, though, he looks and feels more vital, more current, than he does donning the ’60s polka dots and shades rehashing “Like a Rolling Stone” for Unplugged. “Delia” may be acoustic, and a very old song, but it’s not slow or soft; there’s an energy and power in this club vibe. The camera swirls around Dylan. These are long, slow shots, which Borofsky says were considered boring at the time, but it’s riveting to follow the camera as it gently moves from player to player.

“Jack-A-Roe” begins with a closeup of Jackson picking the banjo, then shifts to Dylan playing guitar high up on the neck. The Supper Club shows are the only time Dylan ever played “Jack-A-Roe” live, which is a shame. It is so powerful. It begins slow and quiet, but then there’s an amazing build, led by Watson’s crashing cymbal. More closeups on his singing; he looks intently focused. You can see Jackson behind him grinning, loving it. The band looks so cool throughout.

Finally, “Queen Jane Approximately” ends this tape. There’s another great shot of the tiny stage, taken from the balcony, showing just how crammed-in they all are together. “See that shot?” Borofsky says. “You don’t get that in a concert hall. You only get that in a bar.” It ends with a standing ovation, the camera zooming out to view the audience one last time. Cut to black.

And that was it. We ejected the second videotape and packed up.

The footage is wonderful. It does exactly what Borofsky said they set out to: Present Dylan in a cool club environment, looking like an artist still creating vital music for excited fans, not some oldies act “fumbling in garbage cans outside the theater of past triumphs,” to quote Dylan in Chronicles. Despite whatever residual bad feelings Dylan may have from laboring over it so long back then, they should reconsider releasing it. It’s an important chapter in Dylan’s revitalization and the transition to the second half of his career that kicked into full gear with Time Out of Mind. Plus…I want to watch it again.

Completely agree re Supper Club being vastly more valuable and real than Bob's Unplugged. As I wrote about the latter in the Bob Dylan Encyclopedia: "MTV Unplugged™ [album, 1995]

The dreariest, most contemptible, phony, tawdry piece of product ever issued by a great artist, which manages to omit the TV concert’s one fresh and fine performance, ‘I Want You’, but is otherwise an accurate record of the awfulness of the concert itself, in which the performer who had been so numinously ‘unplugged’ in the first place ducked the opportunity to use television to perform, solo, some of the ballad and country-blues material from his most recent studio albums, Good As I Been To You and World Gone Wrong. That could have been magical. Instead - instead of seizing this moment and really stepping into the arena - we got the usual greatest hits, wretchedly performed in a phoney construct of a ‘live’ concert. This is what happens when Bob Dylan capitulates and lets overpaid coke-head executives, lawyers and PRseholes from the Entertainment Industry tell him what to do.

Thanks for viewing it for all of us, Ray.