A Track-by-Track Guide to Bob Dylan's 'Through the Open Window' Bootleg Series

Plus a playlist of highlights at the very end

Flagging Down the Double E’s is an email newsletter exploring Bob Dylan concerts throughout history. Some installments are free, some are for paid subscribers only. Sign up here:

Today, we finally get the long-rumored Bootleg Series surveying Bob Dylan’s earliest music. All the way back in 2018, a Rolling Stone headline read, “Bob Dylan Plotting Coffeehouse Years Collection for Future Bootleg Series.” It was tentatively titled The Villager then; turns out the actual name of Bootleg Series 18 is Through The Open Window, 1956–1963.

There’s a lot to dig into. Eight discs packed with studio outtakes, home recordings, concert performances, sideman gigs, and beyond. A lot of this stuff has never been officially released before. Some (though less than many hoped) has never circulated before at all, even via bootlegs. I’ve had this set for a few months and have written a detailed track-by-track guide to read while you listen. For the first six discs at least; the final two, containing the complete Carnegie Hall 1963 concert, I plan on writing something else about.

This is meant as a companion piece to the set itself, and to historian Sean Wilentz’s excellent liner notes, which take the form of a long historical essay telling the story of early Dylan. Wilentz does a wonderful job drawing out that narrative, and I tried not to duplicate his work. Mine is more digging into the individual tracks themselves—what they are, where they came from, what struck me listening to them, what some other good versions are.

I’ve also tried to ID which tracks have never circulated before in any capacity, the tracks where this is the first time any of us are hearing them. I’ve marked those with a * in the track title. (This was at times tricky to figure out, so if you spot an error, please let me know.)

Look, this piece is long as hell. Let’s not waste any more time on the introduction. Put on disc one, press play, and read along.

DISC 1

Never-circulated-before tracks marked with *

* 1. LET THE GOOD TIMES ROLL

December 24, 1956 – Terlinde Music Shop, St. Paul, MN

Possibly the single most historically significant track on this entire set comes right up top. “Let the Good Times Roll” comes from the first tape that Bob Dylan—excuse me, Bobby Zimmerman—ever recorded, on Christmas Eve in St. Paul with two of his buddies from summer camp. They visited a recording studio at the mall where, for five dollars, anyone could roll up and cut a live-to-lathe disc on the spot. Which is just what this trio, calling themselves The Jokers, did. Each side was only four minutes; they crammed bits of six songs onto the first side, bits of two more onto the flip. No originals, just covers of then-contemporary hits like Little Richard’s “Confidential” and Carl Perkins’ “Boppin’ The Blues.”

Lee Ranaldo listened to the full tape for the Dylan Center’s Mixing Up the Medicine book and wrote a fascinating article about it. One paragraph that I think is relevant for the one song snippet we hear here:

I wanted this disc to be something it’s not. I wanted it to be not just the first record Bob ever cut but the first appearance of Bob Dylan on record. But it’s not. It’s three teenagers with a shared musical bug having some fun. But everybody starts somewhere, right? Everyone learns the classics, gathering the forms, before heading off to twist, shout, and rip it up. This acetate documents the apprentice stage. It wasn’t yet exactly Bob Dylan, there in front of the microphone. It’s a kid and his buddies, out larkin’, not the ground-shaking reveal of our illustrious hero. That would come a few years later as the 1950s were turning over and Bob was preparing to head east, to find Woody, and the world, waiting for him.

I’ve seen complaints that they didn’t put the full tape on this box set. From a historical perspective, I understand the gripes. From a musical perspective, though, the decision makes sense. As Ranaldo notes, this is not the sound of “Bob Dylan.” It’s Bobby Zimmerman, a barely-teenager messing around with his friends. I’m sure they were trying their best—five bucks was nothing to sneeze at for 15-year-olds in 1956 (it’s about $60 today)—but this is far from polished. At one point, two of them start singing different lyrics. To me, the most enjoyable part is hearing Dylan Zimmerman on barrelhouse piano in the background.

Honestly, the fact that this kinda sucks makes what’s to come even more impressive. It puts the lie to the idea that Dylan was simply born a genius. He was born with something, clearly, but he just as clearly worked his ass off developing his craft. The difference between this and what we’ll start hearing in just a few tracks is colossal.

(For a better “Let the Good Times Roll” by Bob, check out him doing this song with Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers in 1986).

* 2. I GOT A NEW GIRL

May 1959 – Home of Ric Kangas, Hibbing, MN

We jump forward two and a half years. A lot has happened to Dylan in that time. He played a bunch of shows with The Golden Chords, honing his stage chops. He saw Buddy Holly three days before Holly’s death, a life-changing experience he writes about in Chronicles. When this tape was made, he was a few weeks away from graduating high school.

“I Got a New Girl” comes from the same tape he made at friend Ric Kangas’ house as the “When I Got Troubles” that opens the No Direction Home Bootleg Series. A fragment has circulated for years, but this is the first time anyone has heard the full thing. While the audio quality leaves a lot to be desired (prepare for hiss), the performance quality is already quite a bit beyond “Let the Good Times Roll.” Young Dylan has a country croon that sounds like he’s about to go record Self Portrait.

The song is an original Dylan composition, though one that is, to put it mildly, slight. It’s elsewhere subtitled “Teen Love Serenade,” which describes the vibe exactly. He’s come a long way since “Let the Good Times Roll,” but still has a long way to go. I assume the voice harmonizing at the end is Kangas.

At this point we unfortunately skip what many fans hoped would finally be revealed in this set: The Karen Wallace Tape, recorded in May 1960. It was bootlegged decades ago by a pair of fans who visited Wallace at her home. In his book The Dylanologists, David Kinney described how that happened:

Karen and her husband had been thinking about the windfall their tape might bring if they were to sell it, and Karen’s husband was suspicious of the two Dylan fans. He insisted they listen to the tape in the kitchen, where he noisily did the dishes. Karen turned the volume down low and played only snippets of the songs. Then the men went on their way. It would take many years before Karen realized that her husband’s suspicions were well founded: The Dylan nuts had a hidden recorder.

Collectors couldn’t believe how awful the resulting artifact sounded. The thing was notoriously bad. It came to be called the “armpit tape.” ([The taper] said his friend had actually hidden the recorder in a jacket pocket, but it was the more evocative nickname that stuck.) Anyway, the sound hardly mattered. This was a rarity, and it circulated for decades.

There were hopes the Archive would acquire the original tape to release a complete and better-sounding version—it was for sale at one point for $10,000—but that appears not to have happened. Yet.

* 3. SAN FRANCISCO BAY BLUES

4. JESUS CHRIST

September 1960 – Home of Bob Dylan, Minneapolis, MN

These two tracks come from what fans sometimes call the First Minnesota Party Tape, though “party” may be a generous word. Only five people were confirmed there: Dylan, girlfriend Bonnie Beecher, her sorority sister Cynthia Fisher, friend Bil Golfus, and a budding 15-year-old taper named Cleve Pettersen. Pettersen had found his way into the Minneapolis coffeehouse scene around the time Dylan arrived in town to go (or, more often, not go) to college. He’d purchased one of the first commercially available, portable reel-to-reel tape recorders at Radio Shack and would record anyone who would let him.

Pettersen’s son Leif wrote about his dad making this tape in Salon. The whole thing is a really interesting read. Here’s a relevant sample:

Dinkytown’s folk performers were mostly interchangeable, performing the same songs with roughly the same delivery, my dad recalls. Among this crowd, Dylan wasn’t considered to be one of the best, but the upside was he had a burning curiosity to hear what he sounded like while performing. Dylan wasn’t his top choice, he was simply grateful college kids had agreed to briefly let him into their circle.

So, one afternoon my dad and Golfus lugged that beast of a tape recorder to Dylan’s ground-floor apartment on Fifteenth Avenue SE (the asbestos-filled building was demolished in 2014), for a living room jam session. Also present at the “party” was girlfriend Bonnie Beecher (who would one day marry Grateful Dead/Woodstock character Wavy Gravy) and friend Cynthia Fisher.

Over the course of roughly two hours, as Bob, Bonnie, and Cynthia demolished a bottle of wine, they recorded twelve songs, about thirty-one minutes in total length. All the songs were covers by artists like Woody Guthrie and Jimmie Rodgers, including “Come See Jerusalem,” “I Thought I Heard That Casey When She Blowed” and “I’m Gonna Walk the Streets of Glory.” There’s also a one-minute original song Bob wrote commemorating the laziness of his roommate, Hugh Brown.

These are the first songs that to me sound less than “Bobby Zimmerman” and more like “Bob Dylan”—at least the early version. After all, one’s a Woody Guthrie cover, and another’s a Jesse Fuller song he was still covering into the 1980s (G.E. Smith told me about playing that song with Bob). Both songs have a tangential Rolling Thunder connection too: Ramblin’ Jack performed “San Francisco Bay Blues” during his set most nights, and Dylan sang the traditional folk song “Jesse James”—from which Guthrie lifted the tune for “Jesus Christ”—backstage, as heard on the box set.

Personally, I wish they’d included “Talkin’ Hugh Brown,” a song Dylan seemingly made up on the spot roasting his roommate. He calls him a “lazy bastard.”

* 5. EAST VIRGINIA BLUES

* 6. K.C. MOAN

* 7. HARD TRAVELIN’

Late 1960 – Madison, WI

“Time for some other stuff that isn’t Woody’s,” Dylan says by way of introduction in this previously-unheard Madison 1960 tape. Clearly he was already drawing heavily from the Guthrie songbook. This was recorded when he had left Minneapolis and was heading east in fits and starts—first to Chicago around Christmas, then backtracking to Wisconsin, when this tape was made, before finally finding a ride to New York City in late January. Archivist Parker Fishel teased this tape to me three years ago:

Bob’s on his way to New York City for the first time in late 1960, early 1961. He stops at Madison, Wisconsin. It’s a recording of him and Danny Kalb and a guy named Sam Chase. Before they acquired it, it was totally unknown.

Is this a live performance? A jam with friends?

It’s just a guitar pull. Three guys sitting around like, “Oh, have you heard this?” They’re like, “Who wrote that?” He’s like, “Woody Guthrie wrote that!” It’s great, and it’s this snapshot before the thing happens.

The first song, “East Virginia Blues,” we heard Dylan do a decade later with bluegrass great Earl Scruggs. This tape has the best vocals so far—and the first harmonica playing, which already sounds great, if not quite as virtuosic as it would get in the coming year. “I heard that down south from some old guy,” Dylan claims at the end. Here’s the later Scruggs version to compare:

Dylan likely knew Harry Smith’s iconic Anthology of American Folk Music set already, as both “East Virginia Blues” and “K.C. Moan” come from it. You can hear another version of this old work song on the earlier Minnesota Party Tape, but this one sounds much better. Whoever’s picking on the second guitar (Kalb, I’m guessing) adds a lot, teasing Bruce Langhorne’s accompaniments a few years down the line.

Finally, we get another Guthrie tune, “Hard Travelin’”—and, for a second time, Dylan’s harmonica. The only version of this song we previously had comes from Cynthia Gooding’s radio show in 1962, but he did this version with his friends who, in addition to adding more nifty guitar licks in the background, join in singing the “I thought you know’d.”

8. PASTURES OF PLENTY

9. REMEMBER ME

February 1961 – Home of Bob and Sid Gleason, East Orange, NJ

Now a couple tapes that will be familiar to many, even if they count as officially unreleased. First is two tracks from the so-called “East Orange Tape,” recorded at the home of Bob and Sid Gleason. The Gleasons were friends of Woody’s who lived near his hospital, and every Sunday would host him at their house. The Gleasons’ living room—not the hospital, as depicted in A Complete Unknown—is where Bob first met Woody. It’s also where he recorded this tape.

Appropriately enough, the excerpt here begins with a Guthrie tune, “Pastures of Plenty.” Dylan’s singing is softer and more delicate than much of what we’ve heard so far, less forced and frenzied. You also get harmonica interludes between almost every verse, and his first fingerpicking in evidence. It’s a mesmerizing performance, my favorite so far. Though I expect I’ll say that a lot; that’s kind of the entire premise of this set, that he’ll get better and better as time passes. (It’d be weird if he peaked in 1956!)

“Remember Me (When the Candle Lights are Gleaming)” is a country weeper originally by Scott Wiseman, who wrote it, and his wife Lulu Belle, who were termed the “Sweethearts of Country Music” in the ’30s and ’40s. It’s a beautiful performance. You can see him sing the song again a few years later in a Don’t Look Back outtake, with Joan Baez harmonizing:

10. SONG TO WOODY

11. TALKIN’ BEAR MOUNTAIN PICNIC MASSACRE BLUES

September 6, 1961 – The Gaslight Cafe, NYC

Two songs from another iconic early tape—The First Gaslight Tape—follow. We’re skipping out of the chronology quite a bit here, jumping months ahead to September for these two tracks. Perhaps the compilers wanted signs of a budding genius to appear earlier in the set than they otherwise would.

I interviewed Terri Thal, who recorded the tape, earlier this year. She was Dylan’s manager at the time, before Albert Grossman swooped in. She told me why she made this tape:

Initially, all I’m going to do is try and get him some work because he has to earn a living. I needed something to play for potential employers and club owners, so I cut a tape at the Gaslight. I took it to Philadelphia and I took it to Boston and I took it to Saratoga Springs. Everybody said, “Go away.”

No offense to “I Got a New Girl (Teen Love Serenade),” but “Song to Woody” and “Talkin’ Bear Mountain Picnic Massacre Blues” are the first major original compositions on this set. “Bear Mountain Picnic” is the first sign on this box of something that struck me so much doing my early-tapes series: How funny he was. These early sets were as much comedy routine as musical performance. Sadly we only get a brief moment of BobTalk here, but the song itself is hilarious, and on this, the first proper concert tape, you can hear the audience laugh at the many punchlines.

For something like this, where we’ve had the full tape for ages, I was curious whether this official version offers better sound quality. It doesn’t. This sounds about the same to me as the one we’ve had. Which is fine (just a little hissy), but for some of the stuff we’ve had so long, I was hoping it would at least sound better; they did promise this set was “all from brand new tape sources.” (Good news: It does on some later tracks I’ll compare.)

* 12. AIN’T NO GRAVE

Summer 1961 – Home of Mell and Lillian Bailey, NYC

Now we jump back to the summer of 1961, before we will jump back even further to May. The chronology is all jumbled up here.

The Bailey Tapes were one of the major Dylan Archives acquisitions from the last few years. These comprise a half-dozen previously unknown reels of parties held in New York City by folk and calypso enthusiasts Milton and Lillian Bailey. It’s not clear how many Dylan performances are on them, but we get two on this set, this one from a 1961 tape, then one from a 1962 tape on disc 3.

Here we have a song we’ve never heard Bob Dylan perform before in any context, the oft-covered gospel tune “Ain’t No Grave” (I know it from the posthumous Johnny Cash album of the same name). This is an exciting one in that it is the first song on the set we have never heard Dylan sing before, in any context. The song feels right in line with Dylan’s debut album, this cherubic young man singing songs about dying. The vocals aren’t that convincing, but the tricky blues runs he plays on guitar are impressive.

* 13. I AIN’T GOT NO HOME

May 13, 1961 – Coffman Theater, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN

I don’t think anyone even knew this concert tape existed before this set was announced. In the liner notes, Wilentz reports that the occasion was a hootenanny at the university student union. The event immediately predated the Second Minnesota Party Tape, from which the next two tracks will come.

The song we hear is another Guthrie number, “I Ain’t Got No Home,” which Dylan would reprise as part of his three-song set at the 1968 Woody Guthrie tribute concert with The Band. As so many of these early performances are, it’s as much a showcase for flashy harmonica playing as anything. I noted when doing the aforementioned Earliest Concert Tapes series that, when you listen to them, you understand why Dylan’s first recording gigs were all harmonica bookings. It was an obvious early talent, even before he’d shown much aptitude for songwriting and he didn’t mind showing it off. As opposed to something like “Sally Gal,” which seemingly only exists to let him rip harp solos, “I Ain’t Got No Home” is a beautiful song that he sings tenderly.

Here’s the Bob and The Band ’68 version. It’s, spoiler alert, much louder.

14. DEATH DON’T HAVE NO MERCY

15. DEVILISH MARY

May 1961 – Minneapolis, MN

We heard the first “Minnesota Party Tape” on tracks three and four of this disc. Now here’s the second, from eight months later. The Second Minnesota Party Tape contains 25 songs, and it’s worth seeking out beyond the two fragments included here. Of those, he bails early on the Rev. Gary Davis’s “Death Don’t Have No Mercy,” muttering, “That gives you some sort of idea how it goes.” Given that at the start he was talking about the chord changes, I’m guessing he was showing someone else how to play it. That’s how he learned so many early songs himself of course, whether in the green pastures of Harvard University or elsewhere.

Then we get another harmonica showpiece. “Devilish Mary” is a traditional song from the 1920s that Dylan also ends quickly. Personally, I wish they’d included Dylan doing Guthrie’s children’s song “Car, Car” from this tape, which consists largely of Bob making silly motor sounds. There’s a good longer article about this tape at Dylan Revisited.

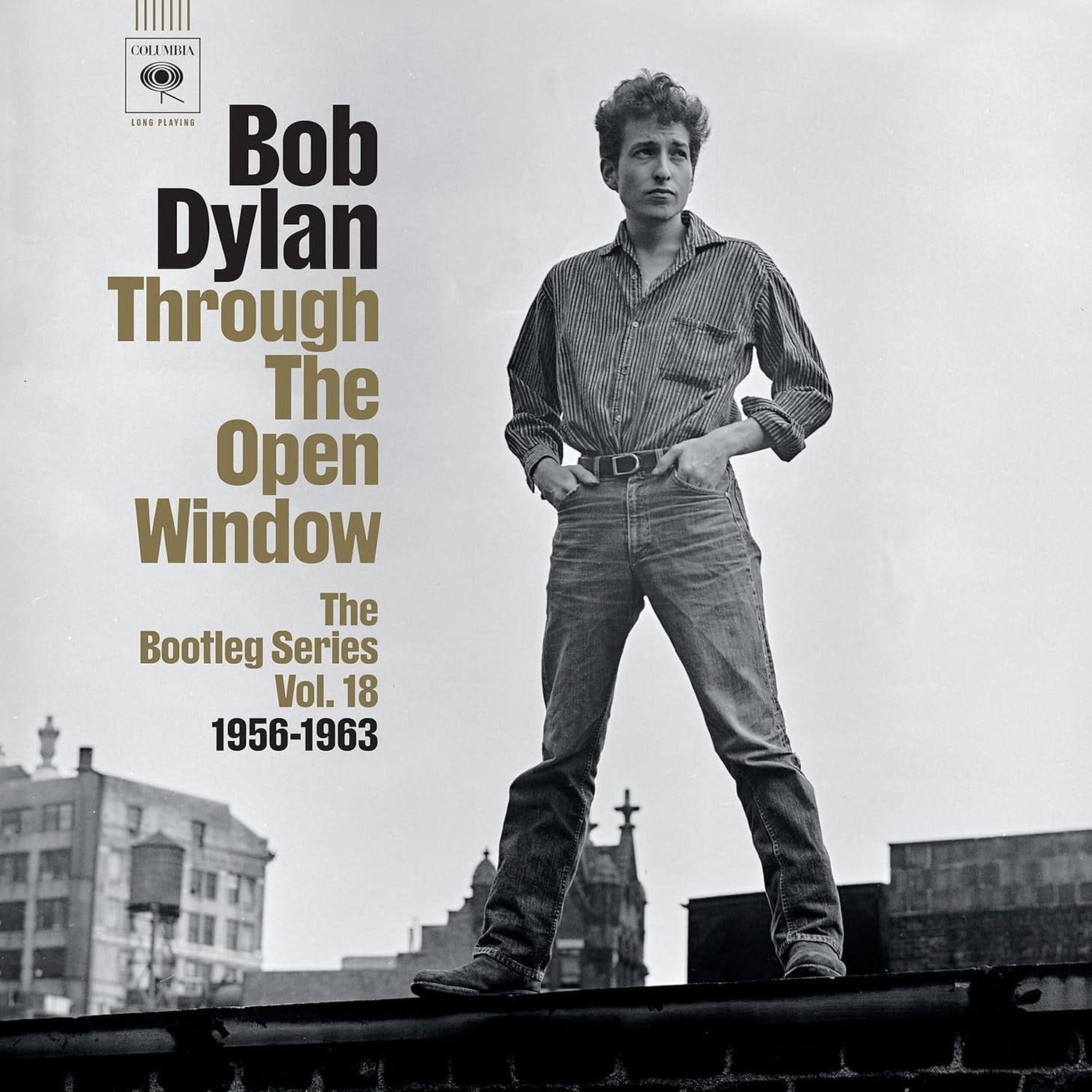

16. Introduction: RIVERSIDE CHURCH

17. HANDSOME MOLLY

July 29, 1961 – Saturday of Folk Music (WRVR-FM), Riverside Church, NYC

One song, plus the host’s intro, from the famous Riverside Church 12-hour folk concert I wrote about here. Dylan only did five songs, and they all circulate. “Handsome Molly” is an excellent choice to represent this performance. Here’s what I wrote in that piece:

This song must have been a staple of this era of Dylan, as he performs it on two later tapes too. This version takes a while to get off the ground, with a few false starts. The reason becomes clear at the end, when Bob starts complaining about his harmonica holder, which will become a running joke throughout (even the announcer eventually gets in on the action). It’s apparently just a coat hanger Bob bent into shape, and not very effectively.

When he finally does get going, he sells it. It’s a sad ballad of heartbreak, recalling many such songs he’d write himself in those early years (“Eternal Circle,” say). He sounds appropriately mournful, and adds some nice little guitar figures to the basic strumming. One thing that strikes me listening to this is how similar the musical approach is to how he has his bands back him now—they can play plenty loud when he’s not singing, but, when he is, retreat so far in the background they’re almost silent. He uses his guitar the same way here. Perhaps that concept dates back to the folk era, where the most important thing was to not bury the words.

This version cuts the false starts and all his bitching about the malfunctioning harmonica holder. Understandable, but they’re fun to hear to put this into context. Again, the full tape is worth seeking out.

* 18. Introduction: SEE THAT MY GRAVE IS KEPT CLEAN

* 19. SEE THAT MY GRAVE IS KEPT CLEAN

* 20. THE GIRL I LEFT BEHIND

* 21. Introduction: PRETTY BOY FLOYD

* 22. PRETTY BOY FLOYD

23. RAILROADING ON THE GREAT DIVIDE

October 1, 1961 – Gerdes Folk City, NYC

The next six tracks (four songs and two spoken intros) come from the Gerde’s Folk City concert I wrote about earlier this year. Credit where it’s due to the compilers for mostly choosing tracks that did not previously circulate. Only the Carter Family tune “Railroading on the Great Divide” was out there before this. (Interestingly, Clinton Heylin reports in his latest Dylan biography that Dylan’s debut album was at one point going to be titled The Great Divide. Was this song going to be on there?).

We get three never-heard songs, one from his debut: “See That My Grave Is Kept Clean,” performed here with extra grit (listen to him reach low to growl certain syllables). He also sings a few verses not on the album, drawn from other versions of this song or even other blues songs (the “bloody spade” bit is usually associated with “Motherless Children” or “Gospel Plow”):

Today has been a lonesome day (x3)

And it looks like tomorrow’ll be the same way

It’s a long old road that’s got no end

It’s a long old trail that never turns

It’s a long old road that’s got no end

It’s a bad wind that never change

You can dig my grave with a bloody spade (x3)

You can see that my digger gets well paid

“Thank ya, all six of ya,” he says with a laugh at the end. I guess Robert Shelton’s famous New York Times concert review a few days earlier hadn’t drawn the big crowds. Then he continues: “This is a Brazos River song. Brazos River is in the eastern part of Texas.” The song is the traditional song “The Girl I Left Behind,” also sometimes called “The False-Hearted Lover.” In radio performance of it a few months later, he claimed, “I learned it from a farmer in South Dakota, and he played the autoharp. His name is Wilbur. Met him outside of Sioux Falls when I was there visiting people and him, and I heard him do it. I was looking through a book one time, I saw the same song and I remembered the way he did it.”

Even at this age, Dylan can sell the hell out of a slow, tragic ballad like this. It’s maybe his best vocal performance so far. It sounds like a song he might have revisited on Good As I Been to You. In fact, though, he actually attempted it again during the Empire Burlesque sessions, which seems like an odd choice. Not sure it would benefit from synths and drum machines.

His jug band buddy Jim Kweskin joins for “Pretty Boy Floyd” and all that subtlety goes out the window. Bob strums hard and sings harder, distorting the mic of radio host and folksinger Cynthia Gooding, who recorded this concert for her radio show. It’s a pretty weak track, but I’m glad they were having fun.

24. Introduction: FIXIN’ TO DIE

25. FIXIN’ TO DIE

1961 – Folklore Center, NYC

I’ve been waiting to hear this one again ever since archivist Parker Fishel, who helped put this set together, hipped me to it back in 2022. It blew me away hearing it at the Dylan Center, and it blows me away again here. It’s Bob Dylan and Dave Van Ronk belting at top volume. Before they begin though, you hear the pair joking with Gooding, who’s again taping. “You got time for another song?” she asks. “Sure,” Dylan responds. “We already forced everybody outta here.” There’s a fun thread running through this set of young Dylan performing for nearly empty rooms (just wait until we get to the Finjan Club).

It’s Dave who suggests “Fixin’ to Die.” Bob comes back with “Pretty Peggy-O.” “That’s a Scottish song. I recorded that to prove there’s no such thing as a Scottish song. It’s all a farce. There’s no Scotland at all.” Huh? Van Ronk laughs uproariously at this non sequitur. It sounds like everyone is feeling…loose. At any rate, they do Van Ronk’s pick.

The “Fixin’ to Die” is as good as I remember, quite a bit better than the album version, with Van Ronk belting, and picking, along with Bob. It’s got a funky flair now, uptempo and, despite the downer lyrics, a whole lot of fun.

(Also while writing this I discovered this has actually circulated for a while—I could have been listening to it this whole time. Doh!)

26. I’LL FLY AWAY – Take 1 (Alternate Take)

September 29, 1961 – Carolyn Hester sessions, Studio A, Columbia Recording Studios, NYC

The final track of the first disc comes from Dylan’s first recording session, playing harmonica for Carolyn Hester, who John Hammond signed to Columbia just before Dylan. It’s the gospel tune “I’ll Fly Away,” an alternative version first released as a bonus track on a 1994 CD re-release of Hester’s debut. It’s the first song here where we don’t hear Dylan’s voice. Just his harmonica, wailing away whip-fast. I’d say it’s of more historical import than anything, partly because I don’t particularly like Hester’s too-clean singing here. Bob’s harmonica is fine, but better elsewhere.

This Hester session is historical for a big reason though: It’s where Dylan met Hammond, who would sign him to Columbia and basically give him his career. In No Direction Home, Shelton (who wrote the famous Times review around the same time) recalls Dylan telling him the story the very same day. He reports Dylan told him:

I don’t want you to tell anybody about this, but I saw John Hammond, Sr. this afternoon and he offered me a five-year contract with Columbia! But, please, man, keep it quiet because it won’t be definite until Monday. I met him at Carolyn’s session today. I shook his hand with my right hand and I gave him your review with my left hand. He offered to sign me without even hearing me sing! But don’t tell anyone, not one single soul! It could get messed up by someone at the top of Columbia, but I think it is really going to happen. Five years on Columbia! How do you like that?

This is a slight exaggeration—apparently they actually first met at a Hester studio rehearsal a couple weeks earlier, before Shelton’s review ran—but the fact is this Hester session occasioned Dylan meeting Hammond is true.

DISC 2

Never-circulated-before tracks marked with *

1. Introduction: IN THE PINES

2. IN THE PINES

3. GOSPEL PLOW

4. Introduction: YOUNG BUT DAILY GROWING

5. YOUNG BUT DAILY GROWING

6. MAN ON THE STREET

7. THIS LAND IS YOUR LAND

*8. PRETTY POLLY

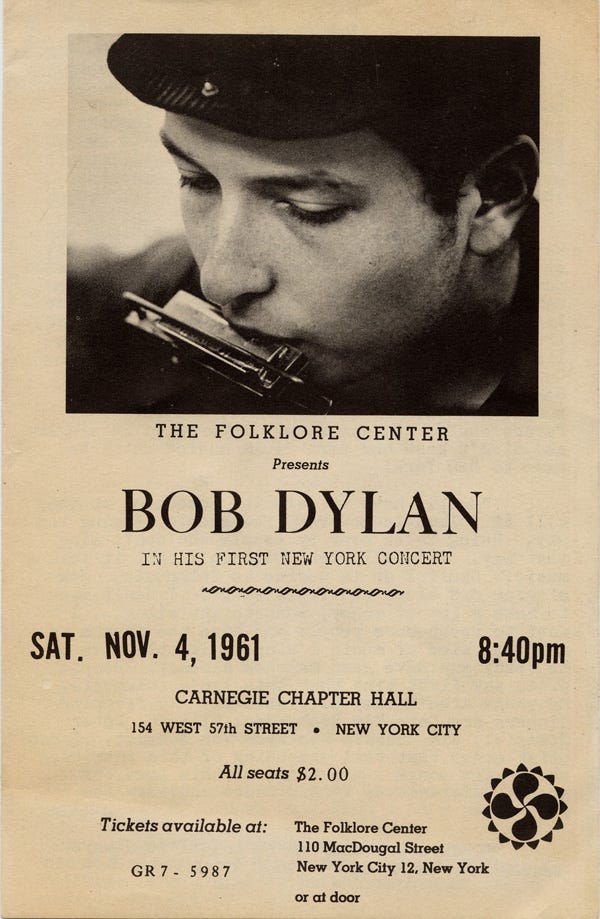

November 4, 1961 – Carnegie Chapter Hall, NYC

Disc two kicks off with six songs (plus two intros) from Dylan’s poorly-attended Carnegie Chapter Hall concert in 1961. It was billed as his big coming-out, his first proper concert with tickets and everything. It flopped, hard. I wrote quite a bit about it here.

One of these six songs has never circulated before: the murder ballad “Pretty Polly.” It’s a shame they didn’t include more uncirculating songs in the mix; I know there is tape of five more. That includes Dylan making more motor-vehicle noises and horn-blowing “a-woo-ga”s on another version of Woody’s children’s song “Car, Car.” Maybe Bootleg Series 19 will just be a dozen different versions of “Car, Car.”

If the melody of “Pretty Polly” sounds familiar, it’s because Dylan would soon borrow it for “The Ballad of Hollis Brown.” He played it a lot in those early days (including on the First Gaslight Tape, where unlike here he added harmonica), but dropped it, understandably, when he had his own song with the same tune. It’s a terrific performance, with him holding syllables to their breaking point and playing with volume dynamics, belting and strumming loud only to cut both down to a whisper in an instant.

The high points to me from this chunk are not the six songs though. It’s the two intros! 1961 Bob was chatty as hell onstage. When I wrote about this show, I transcribed all the BobTalk. It was so long, and so funny. Here are the bits from the songs on this set:

Before “In the Pines”:

Kinda got lost coming up here tonight. Took the subway. Got off somewhere on 156th Street. Started walking back. I got hung up in a Cadillac store. So I’m not here so on time. Almost run over by a bus. I took another subway. Down to 34th street and I walked up here.

Come pretty prepared tonight. I got a list on my guitar. This is a new list. I used to have one on my guitar about a month ago; that was no good. Figured I’d get a good list. So I went around and put the list on first. Then I went around to other guitar players and I sort of looked at their list and I copied down songs on mine. Some of these I don’t know so good…

This is a story about a little girl running all over, finding out about life. She’s going out at night, coming home, keeping late hours. Finding out just what makes up life. 11 years old.

Before “Young But Daily Growing”:

I must admit before I came I learned funny folk songs in New York. I learned about, … well since I been here now since …, February, last February. I’ve learned about, oh, 4 or 5 new songs I never heard about before. And one I never heard about was this one. There’s this Irishman. Liam Clancy, sings this one. This is a straight copy. Straight imitation. I don’t imitate the voice so much, I can’t get that accent down quite good enough. It’s an Irish one though.

Very sad song. Maybe this is the American version of the Irish version of Liam Clancy’s version. Heard Liam sing this in the White Horse Bar. Irish bar.

Before “Man on the Street”:

I’ll sing you a song I wrote— (In response to something in the audience I’m guessing:) Maybe it was time to go out or something and have a cigarette. Got no name really to this one.

Before “This Land Is Your Land”:

Another Woody Guthrie song here. This is... I haven’t done too many Woody Guthrie songs, since a long time ago, so I’m gonna do a few of them tonight. This is one by a special request for this.

For “Gospel Plow,” it’s just him messing around with his capo at the start, to the audience’s audible amusement. It’s another one where, like “See That My Grave Is Kept Clean,” you hear him digging low for those growly accent notes.

* 9. MAN OF CONSTANT SORROW – Rehearsal (Alternate Take, Nov 20, 1961)

10. HOUSE CARPENTER – Take 1 (Outtake, Nov 22, 1961)

* 11. YOU’RE NO GOOD – Take 2 with Take 6 Insert (Alternate Take, Nov 20, 1961)

12. HE WAS A FRIEND OF MINE – Take 2 (Outtake, Nov 20, 1961)

13. RAMBLIN’ ROUND – Take 2 (Outtake, Nov 22, 1961)

Bob Dylan sessions Studio A, Columbia Recording Studios, NYC

Everything else up until this point has been live, in concert or in somebody’s home (or in one case as a sideman for someone else’s studio session). This is the first taste of Dylan in the studio recording for himself. It’s a treat to hear. Thankfully, they include some studio chatter too. After a rehearsal of “Man of Constant Sorrow,” you hear this dialogue between himself and, I assume, producer Hammond.

John: “What was the name of that Bob?”

Bob: “‘Man of Constant Sorrow’”

John: “Man of con–”

Bob: “Did you get that?”

John: “I did.”

Bob: “Did you like that one?”

John: “Sure, it’s alright. Who wrote that?”

Bob: “I don’t know. I don’t know who wrote that.”

John: “Has it been recorded?”

Bob: “Not that way.”

John: “How has it been recorded?”

Bob: “A different way I guess.”

John: “Who did it?”

Bob: “Judy Collins did it, but not a version like that. That’s a different one. Judy Collins on Elektra.”

John: “Elektra. We’ll find out from Elektra who wrote the damn thing then.”

Bob: “Okay.”

Not the most profound conversation maybe, but a fun window into how these sessions actually went. The most telling moment is Bob sincerely asking, “Did you like that one?” He’s looking for approval in a direct, vulnerable way he wouldn’t for much longer.

The other fun spoken-word bit here is Dylan’s intro to “You’re No Good,” which he claims he learned from a cowboy who just got back from California. “He was born on a 200-acre ranch in the dusty plains of Connecticut,” he jokes. Unlike the studio chatter, this dialogue was seemingly under consideration to be included on the album, just like the “green pastures of Harvard University” for “Baby Let Me Follow You Down.” Maybe they decided including two jokey spoken-word intros about where he learned his songs was redundant, but I like it. It livens up one of the less memorable songs of the debut. He even stops the song to ask Hammond, “Can I just leave that little introduction in there?”

A few months ago, someone was briefly selling downloads of the full session tapes for Dylan’s 1961 debut album online. So while some of these songs have technically circulated, it wasn’t widely. This version of the Woody cover “Ramblin’ Round” is a nice performance, but a little tentative. I can see why they dropped it. “Song to Woody” is a much more effective Guthrie tribute for the first album. This doesn’t have the power of the harmonica flourishes on “Man of Constant Sorrow,” the tricky guitar of “House Carpenter,” or the emotive vocals on “He Was a Friend of Mine.”

14. Story: EAST ORANGE, NEW JERSEY

15. STEALIN’

16. PO’ LAZARUS

17. DINK’S SONG

18. I WAS YOUNG WHEN I LEFT HOME

19. IN THE EVENING

20. BABY, LET ME FOLLOW YOU DOWN

21. COCAINE

December 22, 1961 – Home of Bonnie Beecher, Minneapolis, MN

The next seven songs—the longest single block so far—come from what is usually called the “Minnesota Hotel Tape.” Despite the name, it was not recorded in a hotel, but in former girlfriend Bonnie Beecher’s Dinkytown apartment (a regular crashpad for touring musicians, hence its nickname, “The Minnesota Hotel”). It’s one of the first unofficial Dylan recordings to ever circulate, with ten tracks appearing on what some call the first-ever bootleg, 1969’s Great White Wonder.

The selection here kicks off with a funny bit of semi-scripted BobTalk. Bob impersonates a Catskills comic, spinning a yarn about a show in New Jersey where he was paid in chess pieces. Noel Stookey of Peter, Paul and Mary remembered this routine when we spoke. Here’s what he told me:

He came back about a month later, after working a chess club in New Jersey, and asked if he could go on. I recognized him and said sure. Knowing ostensibly what kind of music he was going to do, I segued him in between a flamenco guitar player and my own comedy routine.

He got on stage and began to do a folk song called “Buffalo Skinners.” It tells the story of a man who’s out west. He gets a job working for a group of people skinning buffalo hides. At the end of the season, he wants to move on. He goes to payroll, and they pay him in buffalo skins. He says, “What am I supposed to do with these?” The guy says, “Oh, just take them to the general store and trade them off.” So he goes to the general store, and he gets supplies for his trip further west.

Well, Dylan starts singing this song that has those same chords. Only this is the story about a folk singer who works at a chess club in New Jersey. At the end of the gig, the proprietor pays him in chess pieces. Dylan says, “What am I supposed to do with these?” “Just take them to the bartender. They’re like currency.” So Dylan goes, sits at the bar, orders a beer, pays with the king, and gets two rooks in change. [laughs]

That blew my mind. In retrospect, it is obvious to me that Dylan had a sense of what folk music was. That its reach was much broader than the specific story. That it could communicate concepts borrowing on tried and true traditional forms. Shortly after that, I recommended him to Albert Grossman, who was Peter, Paul & Mary’s manager. It wasn’t too long after that Dylan became part of his stable.

Bob’s retelling here though is not a song; it’s just the spoken-word version of the story. It leads into “Stealin’,” a traditional song that was a staple of his repertoire at the time (he also did it at the Finjan show I wrote about recently). That Finjan version has a zip this one lacks. Interestingly, he rehearsed “Stealin’” with the Grateful Dead 25 years later. You can hear that Dylan-and-the-Dead version below, which sounds a whole lot different than this.

Two more traditional covers follow, “Po’ Lazarus” and “Dink’s Song” (previously released on Bootleg Series 7). Both he would also revisit later: “Po’ Lazarus” during the Basement Tapes sessions, and “Dink’s Song” once on Rolling Thunder (accompanied by Joan Baez!). “Dink’s” is one of his great traditional covers around this time, but I’d say “Po’ Lazarus” is a bit lifeless. Having recently listened to a bunch of early live concerts, it’s fun to hear Bob “performing” in a way that, in this more casual environment at a friend’s home, he isn’t. Sometimes that relaxed vibe is a plus; other times, like on “Lazarus” he just sounds lethargic.

“I Was Young When I Left Home” is the only sorta-original song of the set here, though it borrows so heavily from the traditional “900 Miles” (itself adapted around this time to “500 Miles,” a hit for both Peter, Paul, and Mary and Bobby Bare) that in more recent releases it’s been credited as Traditional-Arranged-By. “I sorta made it up on a train,” he claims in the full Hotel Tape, but they cut that bit out here. It showcases some nice picking, and more emotive vocals than we’ve seen in a few tracks. It’s a high point. This is Dylan’s only known performance of it, but it’s become a go-to selection for indie artists who want to cover a deep Dylan cut; there are great versions by Marissa Nadler and Anohni and The National’s Bryce Dessner.

Three more covers follow: the 1930s blues number “In the Evening;” the traditional song that would be wildly reinvented in 1966, “Baby Let Me Follow You Down;” and the blues tune “Cocaine,” which would find a second life in the Never Ending Tour. I’m not sure why they give over so much of this disc to a tape that’s been bootlegged longer than any other. It’s a historical tape though, and “In the Evening” especially is fun, with Dylan tapping his foot along with the playing, and throwing in some passionate harmonica solos.

Meanwhile “Baby” sounds about like the version on the album, and “Cocaine” feels fairly unconvincing at first, until he starts goofing around. The funniest moment is him saying “Guitar!” leading into the instrumental verse, then muttering, “Bad guitar” when he muffs it. The second is the improvised lines that follow: “Here come my baby all dressed in purple / Hey baby, I wanna see your nipples.” Needless to say, that’s not part of the song’s traditional lyrics.

DISC 3

Never-circulated-before tracks marked with *

1. THE DEATH OF EMMETT TILL

2. Conversation: FOLKSINGER’S CHOICE, 1

3. ROLL ON, JOHN

4. Conversation: FOLKSINGER’S CHOICE, 2

5. HARD TIMES IN NEW YORK TOWN

Broadcast March 11, 1962 – Folksinger’s Choice, WBAI-FM Studios, NYC

Cynthia Gooding is the stealth hero of this box set. She’s already recorded a number of the tapes we’ve heard, and now we visit her radio show Folksinger’s Choice, where she conducted one of the best early interviews with Dylan. Honestly, it’s probably worth just listening to the whole thing if you haven’t; it’s a delight. But the sampler platter here will whet your appetite.

We start with “The Death of Emmett Till.” It’s been less than three months since he was singing about nipples in Bonnie Beecher’s apartment, but he sounds a decade older. In the conversation that follows, Gooding calls it “one of the greatest contemporary ballads I’ve ever heard” and praises “some lines in it that make you stop breathing.” Dylan does his aw-shucks routine in response, then mutters some lies about spending six years with the carnival.

Then he debuts a song from Tempest: “Roll On John.” Wait, no, this is a different song with the same name. Not only is John Lennon still very much alive as of this interview, Pete Best is still his drummer! How’s that for situating just how early this all is taking place?

Dylan tells Gooding he learned this song from Ralph Rinzler. Rinzler played mandolin with the Greenbriar Boys, for whom Dylan opened at Gerde’s Folk City. It’s a beautiful fingerpicked ballad, with high held words that he adds vocal grace notes to. This is his only recording of it. It’s another high point of the box set.

Gooding gently prods him to play another new original, and he reluctantly obliges with “Hard Times in New York Town,” while adding the caveat it wasn’t really new anymore. Sure enough, it kind of pales in comparison after he’s just played the much more sophisticated “The Death of Emmett Till.” He was making such quick strides at this point that even a song that’s six months old sounds dusty and stale.

* 6. TALKIN’ JOHN BIRCH PARANOID BLUES

March 1962 – Home of Mell and Lillian Bailey, NYC

We now get a song from the second Bailey Tape, from March 1962, the same month Dylan’s debut album came out. As mentioned earlier (disc 1 track 12), these party tapes were one of the big Dylan Archives acquisitions from the last few years. On paper at least, this is one of the headlines of this set.

“Pete Seeger’s gonna publish this one,” Dylan informs his audience before playing a slowed version of “Talkin’ John Birch Paranoid Blues.” There are a few lyric changes, though nothing major (I do like the small aside “Couldn’t find ‘em…They were too fast for me.”) The listeners bust up so hard at the “red stripes in the American flag” line he has to wait to continue.

Note: A second song from this tape was made available as an MP3 download by the Dylan Center in May 2021, when they announced the Bailey Tapes acquisition. Unfortunately the audio link seems to be gone, but you can read about it here.

7. BALLAD OF DONALD WHITE

September 20, 1962 – Home of Mac and Eve McKenzie, NYC

2012 was the year Sony first released a copyright-extension CD, to combat a recent European law that would make music public domain (that is, available for any random person to release and make money off of) if it hadn’t been officially released after 60 years. The 1962 copyright set was incredibly limited—the cheapest copy on Discogs costs over two thousand dollars, for what’s basically a burned CD!—but naturally was quickly ripped and circulated digitally. Sony has released some version of these sets every year since, so from here on out a lot of this is “rare” but not technically unreleased.

That includes “The Ballad of Donald White,” from the so-called McKenzie Tapes. This lesser-known early song adapts the melody of the 19th-century ballad “The Ballad of Peter Amberley.” Dylan had apparently seen a TV program about Donald White, a Black Death Row inmate. Dylan’s friend Sue Zuckerman told Clinton Heylin, “Bobby just got up at some point and he went off in the corner and started to write. He just started to write, while the show was still on, and the next thing I knew he had this song written.” This is another performance in an apartment; a telephone rings halfway through, but Dylan doesn’t break stride.

This song is presented here out of chronology, likely because the song was first written shortly after “Emmett Till” and “John Birch,” even though this specific recording comes from September. We’ll jump back to Spring 1962 for the next chunk of the disc.

* 8. MIDNIGHT SPECIAL – Rehearsals

9. MIDNIGHT SPECIAL – Take 17 (Alternate Take)

February 2, 1962 – The Midnight Special sessions, Webster Hall, NYC

In fact, we’re all the way back in February 1962, even before the Folksinger’s Choice selection, for two unreleased tracks from Dylan’s “Midnight Special” harmonica sessions accompanying Harry Belafonte. The first is a brief rehearsal clip, a charming one where you hear a bit of chat between Belafonte and Dylan. “Take your time baby,” Belafonte mutters when Dylan complains he can’t get a sound. “Take off your boots.” “Oh, sorry,” Dylan mutters. He sounds nervous. Producer Hugo Montenegro chimes in with some advice.

Then there’s a proper take, a different one than Belafonte put on the album. It sounds pretty similar to the released version. It’s Take 17 though—they must have been really drilling this thing. How many Bootleg Series will we get before a couple discs on “The Midnight Special Sessions”? As on the released version, Dylan plays a short harmonica intro, then a longer solo halfway through.

It’s a moment that clearly stuck with him. He wrote about the session in Chronicles, erroneously calling it his “professional recording debut.” He went on: “Strangely enough, this was the only one memorable recording date that would stand out in my mind for years to come. Even my own sessions would become lost in abstractions. With Belafonte I felt like I’d become anointed in some kind of way.”

10. WICHITA (Album Version)

11. IT’S DANGEROUS (Album Version)

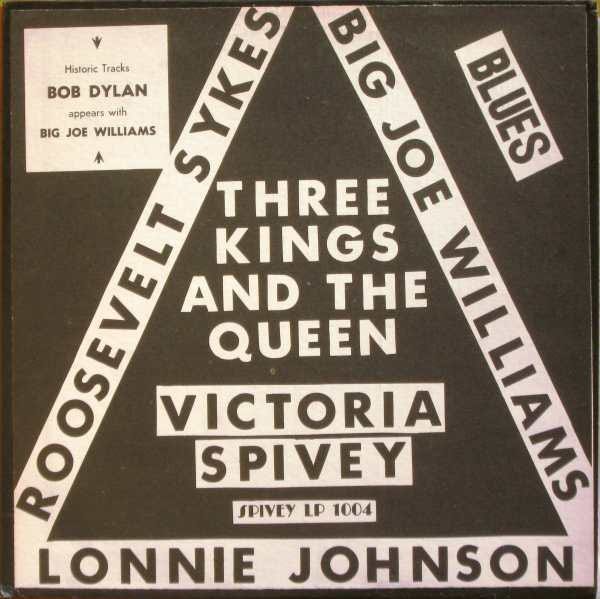

March 2, 1962 – Three Kings and the Queen and Kings and the Queen, Volume Two sessions, Cue Recording Studios, NYC

More harmonica-accompaniment sessions follow. One session, actually, but backing two different singers.

The first is Big Joe Williams, the blues singer and, as seen in a recent entry, nine-string(!) guitarist. Big Joe sings the traditional blues song “Wichita Blues,” which Dylan himself attempted in the Freewheelin’ sessions (albeit with entirely different lyrics). Here, though, Dylan sticks to harmonica, blowing wild solos. Williams enjoys it so much that he gives Bob the endearing, if cumbersome, nickname “Big Joe Little Junior.” It seems like half the song is given over to harmonica solos. It’s Dylan’s most virtuosic harp performance yet.

Then singer Victoria Spivey takes the mic, to sing her own song “It’s Dangerous.” This is a slow blues ballad in the Bessie Smith vein, more of a proper song than “Wichita Blues.” Dylan gets some harp licks in, accompanying Spivey’s own piano playing, letting loose a bit more (though too low in the mix) during the instrumental break.

12. HONEY, JUST ALLOW ME ONE MORE CHANCE

13. TALKIN’ NEW YORK

14. CORRINA, CORRINA

15. DEEP ELLUM BLUES

16. Introduction: BLOWIN’ IN THE WIND

17. BLOWIN’ IN THE WIND

April 16, 1962 – Gerdes Folk City, NYC

After four tracks where we haven’t heard Dylan sing, we dive back with the Gerde’s 1962 tape. I wrote at length about this tape earlier this year. The track I focused on most was the last one here. I wrote:

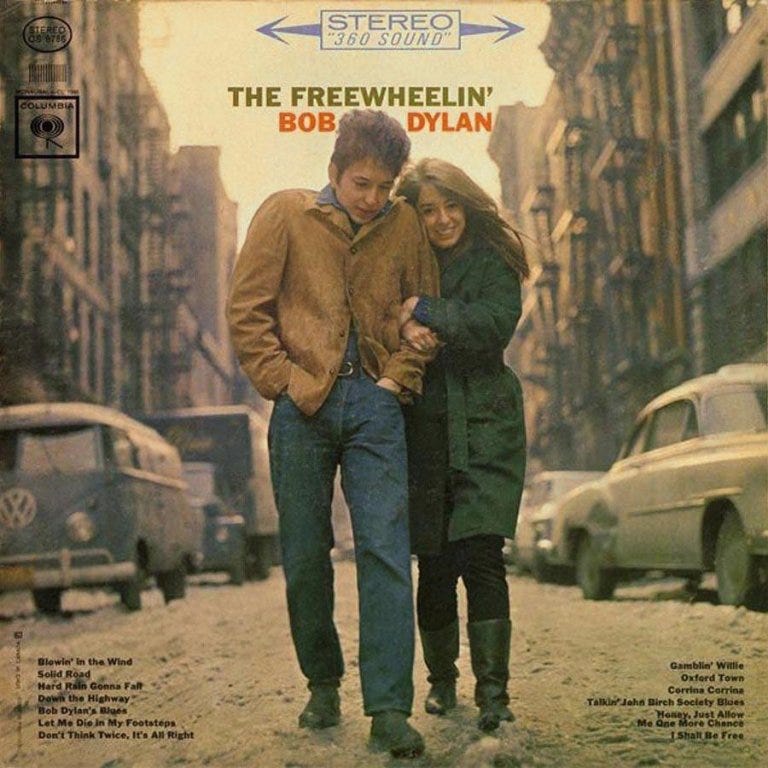

“This here, it ain’t a protest song or anything like that,” Bob Dylan says before his final song on today’s tape, “because I don’t write protest songs.” He then proceeds to debut his new not-a-protest song: “Blowin’ in the Wind.”

Yes, as early as April 1962, when “Blowin’ in the Wind” was a brand-new song he’d written just days before, he was already feeling hemmed in by people calling him a protest singer. It didn’t take until Another Side of Bob Dylan or going electric at Newport. He was pushing against the “protest song” stigma practically since he began writing, well, protest songs.

This may well be the first time anyone heard “Blowin’ in the Wind,” though, as often happens with these very early shows, the details are too vague to state that definitively. “Blowin’ in the Wind” is the obvious headline here, but he debuts two more Freewheelin’ songs at this same show. They’re the album’s two covers though, which makes them more of a footnote: “Corinna, Corinna” and “Honey, Just Allow Me One More Chance” (officially labeled a co-write with the song’s originator, 1920s bluesman Henry Thomas). He hadn’t written any of the other original Freewheelin’ songs yet as far as we know.

He also gives his only recorded concert performance of another cover, the blues traditional “Deep Ellum Blues.” He introduces it by shouting out Big Joe Williams in a way that sounds like Big Joe was also on the bill, saying he learned the song from him. In fact, Bob may be borrowing Big Joe’s guitar. He says, while tuning, “Big Joe plays a nine-string guitar. John Henry couldn’t swing this guitar.” It sounds like he’s struggling with Big Joe’s giant guitar. Then again, Big Joe really did play a nine-string guitar, and I can’t imagine Bob would have known what to do with that.

Of the other two songs on this set, “Talkin’ New York” gets a new verse that earns big laughs from the crowd:

Well I got on the subway, I took a seat

And got off on 42nd Street

I met this fella named Dolores there

He started rubbing his hands through my hair

I went to ten hot dog stands, four movie houses, and a couple of dancing studios

Back on the subway

He also uses a slight variation of the spoken intro he would later give “Bob Dylan’s Blues” on the Freewheelin’ album, saying, “This isn’t like the usual New York songs. Lotta songs you hear nowadays about New York, they’re all the glamor kind. On the 42nd Street Broadway theaters, you hear ‘em all the time. ‘New York, New York, the wonderful town, let’s go to New York for our vacation and see what a great town it is.’ This wasn’t written up there where all those songs were written. This was written down in the United States.”

He then goes into “Corinna, Corinna,” which sounds like a slower, more lethargic version of what would end up on Freewheelin’.

Speaking of Freewheelin’…

18. RAMBLING, GAMBLING WILLIE – Take 3 (Outtake)

19. (I HEARD THAT) LONESOME WHISTLE – Take 2 (Outtake)

April 24, 1962 – Freewheelin’ sessions, Studio A, Columbia Recording Studios, NYC

20. ROCKS AND GRAVEL – Take 3 (Outtake)

April 25, 1962 – Freewheelin’ sessions, Studio A, Columbia Recording Studios, NYC

We get our first three songs from the Freewheelin’ sessions. Again, this would be huge news had they not all been quietly released on the 1962 copyright set back in 2012. But it’s worth giving them a bigger spotlight now. The first is an original number: “Rambling, Gambling Willie.” I actually forgot it’s an original; it sounds so much like an older tune he’s covering (Heylin compares it thematically to “Pretty Boy Floyd” or “Jesse James”). Which probably means it was smart to cut it from the album; as a song, it would pale in the company of “Blowin’ in the Wind” and “Hard Rain.” But, though slight, it’s charming, particularly with how hard Dylan tries to sell it here. This comes from the same session as the version heard on the very first Bootleg Series, but is a different take with an extended harmonica intro.

“Rambling Gambling Willie” was originally slated to be on Freewheelin’—they even pressed up promo copies—then got cut at the eleventh hour alongside three other songs. One of the other three last-minute cuts is also here: “Rocks and Gravel.” This was the single they released when they first announced the box set. It’s another original that sounds like a cover. That’s because it’s based pretty heavily on a song Alan Lomax taped Parchman Farm prisoners singing in the ’40s. Dylan’s friend Harry Belafonte had just covered it two years before this session.

In between the two comes an actual cover, of Hank Williams’ “(I Heard That) Lonesome Whistle.” Alas, they didn’t include the Toad’s Pace version. Now that would have been a change of pace. No, this is, of course, the Freewheelin’ outtake. I really like this performance. There’s a pretty strong argument that he needn’t have bothered including any covers on Freewheelin’—he had enough originals this time—but if he had to, I might have swapped this out for “Honey, Just Allow Me One More Chance.” He sings the hell out of it, adding Jimmie Rodgers vocal yodels on the title line.

21. PATHS OF VICTORY

22. TRAIN A-TRAVELIN’ (Album Version)

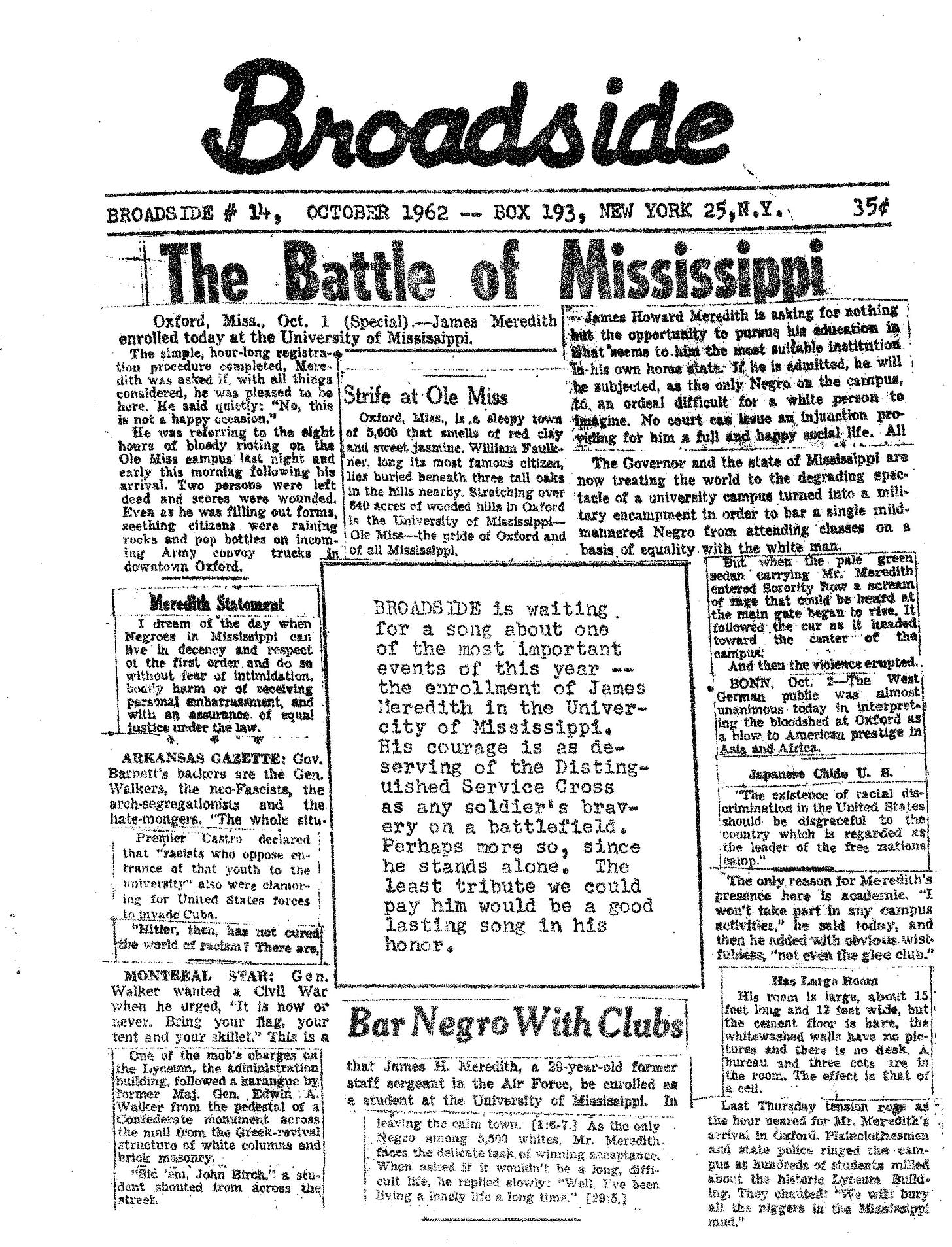

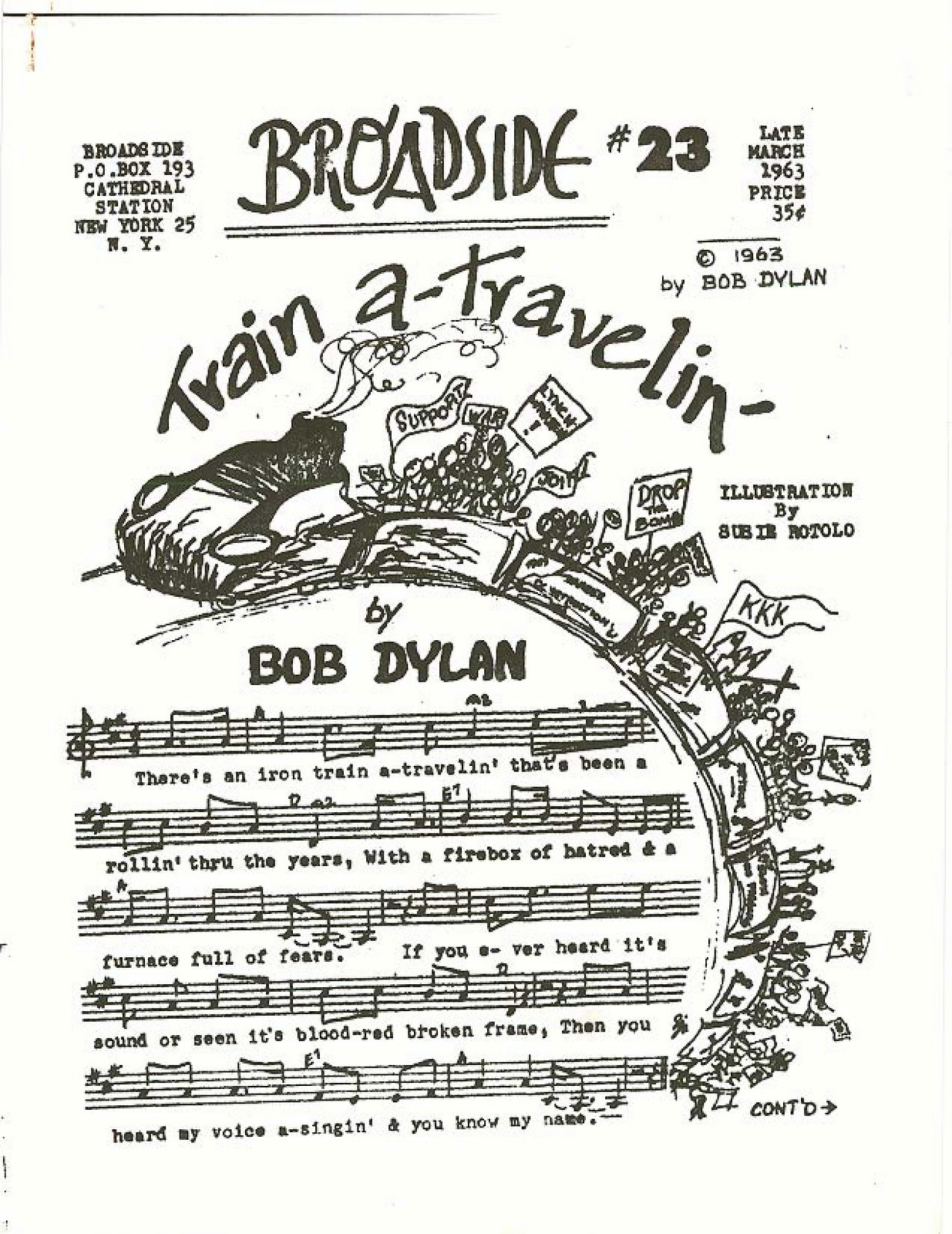

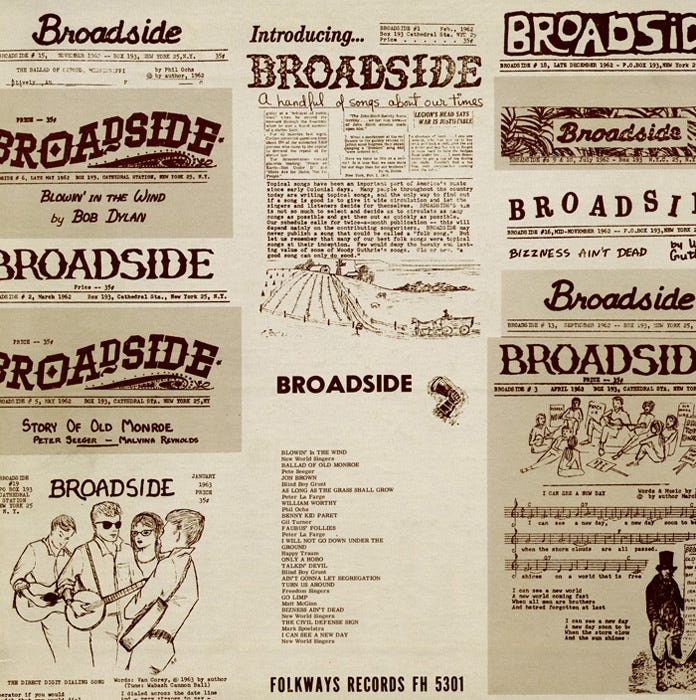

October-December 1962 – Broadside Office, NYC

“Paths of Victory” was a high point of the very first Bootleg Series. That version though was played on piano, and was an outtake from the next album, The Times They Are a-Changin’. This earlier version finds Dylan on guitar and comes from the Freewheelin’ era. Personally, I prefer the other one. Being performed at the Broadside magazine offices, this was likely put down for the purpose of copyright, like the Witmark demos, and so feels underperformed.

The second song is much more interesting. “Train a-Travelin’” is an extremely obscure original from this period, only ever performed on this tape. Fan site Untold Dylan calls it “a forgotten masterpiece,” which feels like a slight exaggeration, but it is good. He only sings three verses, but there are three more (better ones too) he published in writing in Broadside magazine. It’s another very Guthrie-esque song, filled with images of mayhem and evil all aboard this demonic iron train.

When Broadside published it, it came accompanied by a great Suze Rotolo illustration of the titular train and all the “crazy mixed-up souls” carrying pro-war protest signs.

23. HIRAM HUBBARD

24. QUIT YOUR LOW DOWN WAYS

25. LET ME DIE IN MY FOOTSTEPS

26. RAMBLIN’ ON MY MIND

27. BLUE YODEL NO. 8 (MULE SKINNER BLUES)

July 2, 1962 – The Finjan, Montreal, Canada

I wrote a long piece about this Finjan Club show in Montreal—a personal favorite of mine—back in July. This is another one where I have no beef with the five songs they selected to include here, but really you should go get the full tape. Two of this show’s covers were never performed before or since: the traditional “Hiram Hubbard” and Robert Johnson’s “Ramblin’ On My Mind.” Both are on the box set. As is the show’s one original live debut: “Quit Your Lowdown Ways.”

As I noted in that piece, the audience was tiny, and he’s clearly aware he’s being taped. To some degree he is performing for the recording device as much as he is the handful of people in the room. “You better cut all that part off,” he tells the taper after aborting Jimmie Rodgers’ “Blue Yodel No. 8” (sadly they just fade it out in the box set, but the abrupt ending and chatter audible in the full concert). “Or else just put the tuning in. The tuning’s better than that.”

Another great bit of BobTalk, also cut from the version on this set: At one point, he announces, “I’m gonna sing a couple dirty songs now. They’re gonna run out of there and say, ‘Jesus Christ, he don’t sing folk songs. Let’s go listen to the Cumberland Three.’” He then proceeds to sing…“Let Me Die in My Footsteps.” That’s the dirty song?

Point being, if these tracks whet your appetite, go find the full tape. It’s a gem.

DISC 4

Never-circulated-before tracks marked with *

1. BABY, PLEASE DON’T GO – Take 3 (Outtake)

April 25, 1962 – Freewheelin’ sessions, Studio A, Columbia Recording Studios, NYC

Disc four kicks off with another staple of Bob’s early blues repertoire, the oft-covered “Baby Please Don’t Go” by Big Joe Williams, who Dylan was backing just a month before (see disc 3 track 10). Dylan had performed it on the aforementioned Minnesota Hotel Tape and Cynthia Gooding’s Folksinger’s Choice radio show. So it was a natural choice for Freewheelin’, at least when he was considering including more covers on the album. To me, this is one of the best. Dylan’s funky, weird picking backs sprightly vocals and rhythmic harmonica interludes. Listen to how he reaches deep to put a little stank on the first “Turn your lamp down low.” Maybe my favorite of the Freewheelin’ covers.

2. WORRIED BLUES – Take 1 (Outtake)

3. BABY, I’M IN THE MOOD FOR YOU – Take 4 (Outtake)

4. BOB DYLAN’S BLUES – Take 2 (Outtake)

July 9, 1962 – Freewheelin’ sessions, Studio A, Columbia Recording Studios, NYC

The Freewheelin’ sessions jump ahead two and a half months for the next three tracks. The first is a cover, the fingerpicked traditional “Worried Blues,” which will be familiar from the very first Bootleg Series. This is a different take, but sounds pretty similar. Interestingly, Dylan is playing a 12-string guitar on this, not an instrument he played all that often. In a concert years later, Dylan told the audience the first time he heard a 12-string was played by Leadbelly. He then proceeded to play a song of his own on 12-string: “Caribbean Wind,” the only ever performance of it. You can hear the 12-string chime in the intro.

Another song familiar from earlier box sets is “Baby I’m in the Mood for You,” first heard on Biograph and then again on The Witmark Demos. Again, this is a different take, but, also again, it’s not that different. Hearing all these in a row, it really strikes you just how reliant Dylan still is on his harmonica prowess. At this point he’s starting to write great songs (I mean, maybe not this one, but others), but he’s been treated as a harmonica hotshot more than anything thus far, and perhaps he took that image to heart. Any chance he gets to blast a flashy harmonica interlude, he takes. (Incidentally, there’s a good cover of this by—of all people—Miley Cyrus and The Roots.)

Finally we reach the first outtake of a song that actually did make it onto Freewheelin’: “Bob Dylan’s Blues.” He gives it the same “written in the United States” intro heard on the album, indicating that was a planned part of the song, not some off-the-cuff riff. The lyrics, though, are different. This version begins:

I feel like runnin’ down to Shenandoah

I got a home on the highway, I feel I’m bound to go

Bound to go, bound to go, bound to go

Then, later on, another different lyric:

I got a clock in my stomach and a watch in my head

I’m a tickin’ so loud, lord, I’m gonna wind up dead

Yes I will, no I won’t, maybe I will

5. Introduction: TOMORROW IS A LONG TIME

6. TOMORROW IS A LONG TIME

* 7. THIS LAND IS YOUR LAND – The Last Verses

* 8. LONG TIME GONE

August 11, 1962 – Home of Dave Whitaker, Minneapolis, MN

Here’s another of the most exciting reveals from this set: The 1962 Dave Whitaker tape. Dylan’s buddy Tony Glover recorded it at the home of mutual friend Whitaker on a visit home to Minnesota. Tony Glover described the visit in a mid-’80s video interview quoted in Heylin’s Double Life of Bob Dylan:

“He came here again in August … He stopped a couple of days … The trip before, it was real quiet, just Whitaker and a few people. This was [more] like, Dylan Returns! The star returning to his home town; there was a bit of that. Whitaker was having this big open-house party. Bob was pretty drunk, [playing this] real shitty guitar. A dizzy blonde [called] Echo showed up … She was coming on pretty heavy, and he was going, ‘Wait a minute, I got a girlfriend back in New York.’ Dave [Whitaker] and his wife Gretel were having a fight. At one point, [when] there were only three or four people left, Bob started doing ‘Corrina Corrina’; Dave and Gretel were wailing at each other.”

Sounds dramatic! You wouldn’t know it from this tape. Well, maybe the part about him being sloshed; the intros are unusually rambling (and, in one case we’ll hear, unusually vulnerable). Dylan played seven songs, four of them originals, including something called “Talkin’ Hypocrite,” never played elsewhere and unfortunately not included here. Early biographer Robert Shelton quoted one lyric as “What kind of hippo is a hypocrite?” I wish they’d included it! Seems like a missed opportunity.

We do however get three other songs. The first gets the aforementioned vulnerable, if rambling, intro from Bob:

I’m gonna make up some verses to this, the first two verses, but the last verse is the one I wrote the whole song about. I wrote it because it just came into my mind. This here thing came into my mind. My girlfriend, she’s in Europe right now. She sailed on a boat over there. She’ll be back September 1st, but until she’s back, I never go home. It gets kinda bad sometimes. Sometimes it gets bad, most times it doesn’t. I wrote this one especially thinking about that. I just wanted to get it on the tape recording machine. [strums for a while] This is way outta my style. I never write songs in this sort of style. This is the Pete Seeger style. You know, ‘Bells of Rhymney.’ Pete Seeger is Mike Seeger’s older brother.

You might think from that intro that he’s about to drop “Boots of Spanish Leather,” but no, we have to wait until disc six for that. It’s “Tomorrow Is a Long Time.” This is the one song that has circulated from the Whitaker tape, but in awful sound quality. This is a big upgrade. As promised, he does seem to make up the opening verses. Or, at least, they’re not the ones on the recorded version and seem fairly unpolished.

Only if the sky would fall tomorrow

Only if the river ran dry

Only if the rainbow lost its colors

Then I might go home againOnly if the highway stops ramblin’

Only if the ocean turn to sand

Only if the blind could see me singin’

Then I might fall down on my knees and cry

Then the third verse is, again as promised, the one we know (“Only if my own true love…”). Though maybe “verse” is a confusing word to use. He so far only has what will become the song’s chorus melody, but treats it like a verse, changing lyrics each time. There is nothing in place of the song’s eventual actual verses (“If today was not an endless highway” etc). Plenty of these songs have alternate lyrics, but this is in more raw shape than most, missing a huge chunk of the song’s basic framework. A fact Dylan seems aware of, hence the self-deprecating intro.

The next track is even more fascinating. “This Land Is Your Land”—what’s so special about that? Well, as Dylan explains, he’s specifically singing the last verses Guthrie ever wrote. He claims Woody sang them to him personally, which is maybe an exaggeration? My understanding was Woody was not in singing shape by the time Bob met him, hence all his admirers singing to him. Neither of the verses Dylan sings here are brand-new; a quick Google confirms other people have sung them. So they’re not unknown verses, but they’re certainly lesser-known, and probably weren’t familiar to the friends he was singing to.

“Nobody’s ever heard this one,” he mutters before the last song here. “First time I’ve sung it.” The song is “Long Time Gone.” It’s not that different than the versions we already have, though I do like Dylan claiming he just made up half the words when he finishes (doubtful; they’re basically the same as subsequent versions). “I wrote that for myself,” he continues. “I figured I been writing too many songs for other people.”

This entire stretch is a high point of the set and only makes me wish they’d released the entire Dave Whitaker tape. I want to hear more inebriated-Bob banter!

9. A HARD RAIN’S A-GONNA FALL

10. DON’T THINK TWICE, IT’S ALL RIGHT

11. BARBARA ALLEN

12. THE CUCKOO

October 1962 – The Gaslight Cafe, NYC

When Sony announced this box, they made a point of noting that these recordings were taken “all from brand new tape sources.” What exactly that means is a little vague, but I assume it means new transfers of the existing tapes.

I was reminded of my conversation a few years back with Richard Alderson, who recorded the second Gaslight tape. He complained that the official release a few years ago had mishandled his audio:

[When Columbia eventually released Live at the Gaslight 1962 43 years later], they said they searched everywhere for the best possible recordings, but they never came to me. I had the originals all along. They just downloaded a bunch of stuff. It sounds pretty good, but my copies were one-offs directly from the master tapes.

Bob Dylan’s office [subsequently] bought the original Gaslight tapes from me. They own them, but because they released them once with false album notes and claimed a lot of bullshit, unintentionally, about the recordings, they don’t want to issue them again.

Wait, so the official album was your recording, just several generations later, or a totally different recording?

They were my recordings but they were mishandled. I gave the recordings to Dylan’s manager, Albert Grossman at the time. I suppose that the copies that were on the internet were copies of copies. But they were really bad versions. Not at all like my tapes.

Which made me wonder, here we have four of the Second Gaslight Tape tracks again. Are these new transfers? And, if so, is the audio quality better than that Starbucks release 20 years ago?

I’m pleased to report: In this case, yes! Markedly so. I compared all four tracks back-to-back. The quality was not bad back then by any means, but there was a noticeable background hiss. The hiss here is much quieter. Dylan’s vocals come through clearer and crisper. I’m not enough of an audiophile to have noticed if I didn’t make the comparison myself, but when you do you hear a distinct improvement.

They picked four songs from the 17-song set to include, two originals and two covers, which is about the same ratio as the show itself. Alderson said he thought “A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall” is performed at the Gaslight better than anywhere else. Appropriately enough, as according to Wavy Gravy, Dylan wrote the song just upstairs: “Dylan wrote the words to ‘A Hard Rain’s A Gonna Fall’ on my typewriter. A lot of Bob’s early stuff would start with him singing and strumming upstairs [in my room] at the Gaslight, then running downstairs and doing it on stage.”

He’d performed it a couple times already, but the song is only a month or so old. Depending on when in October this Gaslight show took place—the exact date is unclear; many sources say October 15, but this box set, which gives precise dates for most songs, notably just says “October 1962” for this—the Cuban Missile Crisis was either still in full swing, or hadn’t happened yet.

Following that is the first known live performance of another brand-new composition, and another classic, “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right.” It’s so new that he either goofs one line as “Look out your window and I’ll be traveling on / You’re the reason I’ll be gone.” Or maybe he decided later the closing words worked better switched around. Strangely, he didn’t record this at the next Freewheelin’ session a week or two later. He waited another month, then knocked it out in one take.

Following that we get the two covers. First, a song that would later become one of the great covers of the early Never Ending Tour, “Barbara Allen.” This is another where we’re hearing the first recording of Dylan ever performing it, and in fact the only recording of him doing it in the ’60s period. I find it striking how far he’s come as a performer. The first two discs were all him pushing, fighting to show what he can do, particularly in constantly demonstrating his flashy harmonica tricks. This is him pulling—no tricks, not shouting or yelping or harmonica-blasting. Just an intimate, quiet, utterly mesmerizing performance. It’s eight minutes long—the longest song here so far—but he earns every second.

After that “The Cuckoo” comes like a palate-cleanser. Not at the level of the previous three songs, but not really trying to be either. Short, fast, light on its feet. He only performed it one more time, for the BBC play Madhouse on Castle Street a few months later (it doesn’t circulate), though of course would reuse “The cuckoo is a pretty bird / She warbles as she flies” decades later in his own “High Water (For Charlie Patton).”

13. THAT’S ALL RIGHT – Take 5 (Outtake)

October 26, 1962 – Freewheelin’ sessions, Studio A, Columbia Recording Studios, NYC

14. MIXED-UP CONFUSION – Take 10 (Single Alternate Take)

November 1, 1962 – Freewheelin’ sessions, Studio A, Columbia Recording Studios, NYC

15. BALLAD OF HOLLIS BROWN – Take 2 (Outtake)

16. KINGSPORT TOWN – Take 2 (Outtake)

November 14, 1962 – Freewheelin’ sessions, Studio A, Columbia Recording Studios, NYC

17. WHATCHA GONNA DO? – Remake, Take 1 (Outtake)

18. HERO BLUES – Take 4 (Outtake)

19. I SHALL BE FREE – Take 3 (Alternate Take)

December 6, 1962 – Freewheelin’ sessions, Studio A, Columbia Recording Studios, NYC

The fourth disc concludes with a hodgepodge of Freewheelin’ sessions over the next two months. Seeing all the Freewheelin’ sessions spread over the course of a full year on this set—April 1962 to April 1963—makes you understand why two albums from now (Another Side) he’d want to just knock the whole thing out in a single night. Doing it this piecemeal way seems arduous. This chunk all comes from October, November, and December 1962. Notably, the first two are the only sessions that have a backing band. One album in and he’s already going electric. Judas!

The first song here is already establishing his rock-and-roll bona fides. He probably knew the Arthur Crudup original of “That’s All Right,” but he definitely knew the Elvis Presley version. He channels the King ably, albeit with a lot more harmonica. It’s almost a jarring transition after “Barbara Allen” and “Hard Rain” and the rest. One wonders if he’d put this on Freewheelin’ if the later controversy could have been avoided entirely. It’s not just that it has a rockabilly backing band, but also that lyrically this is as far from a topical protest song as you can get.

That old-time-rock-and-roll vibe continues on “Mixed Up Confusion,” an original song that was actually released at the time, fully electric, but as a non-album single where it could be easily ignored and didn’t trouble his “acoustic protest singer” narrative. It sounds like something recorded at Sun Records. This is an outtake version, but it’s pretty similar to the single familiar from Biograph. The biggest differences I noticed are that this version doesn’t have that bit of harmonica at the intro, and that there’s an alternate verse: “Well, I’m too old to lose, babe, I’m too young to win / Now I feel like a stranger in a world I’m living in.” The point of this song is more performance than lyrics though. To me it doesn’t have the kick of “That’s All Right,” even as he tries to channel the same energy. It might be just that “That’s All Right” is ultimately a more memorable song.

Next up, “The Ballad of Hollis Brown.” Eagle-eyed listeners might be thinking, “Wait, that’s not a Freewheelin’ song…” Yep, it wasn’t released until he redid it for The Times. Imagine writing a song this powerful and not putting it on your next album. Which made me wonder listening to this, does it sound unfinished? Nope, but it does include an alternate verse:

There’s bedbugs on your baby’s bed, there’s chinches on your wife

There’s bedbugs on your baby’s bed, there’s chinches on your wife

Gangrene stuck in your side, it’s cutting you like a knife

Good verse! Though maybe two “your baby” verses in a row seemed a little much. Also “chinches” is apparently Spanish for, most commonly, “bedbugs,” which also seems redundant. The other big difference here from the Times version is that the distinctive acoustic picking pattern with the alternating bass notes is not there yet. It’s just a simple strum. This version also has a couple brief harmonica interludes. The Times version is better. He was wise to wait.

“Kingsport Town” will be familiar from the very first Bootleg Series. This is the same take too. Some sources call it a Dylan original, others “Trad. Arr. Dylan,” since he based it pretty heavily on Woody Guthrie’s “Who’s Gonna Shoe Your Pretty Little Feet?” (itself based on an old ballad). In the original Bootleg Series liner notes, the late great Dylan expert John Bauldie wrote:

There are two notable things about this performance: one is the curious Okie accent that Dylan affects as he sings. The other is Dylan’s own distinctive turn of phrase can be heard amid otherwise formulaic lyrics. Just about anybody could have written the lines about the “curly-headed, dark-eyed girl,” but surely only Bob Dylan (and we can hear him come up with the alliteration even as he’s performing the song) could have come up with “Who’s gonna kiss your Memphis mouth when I’m out in the wind?”

Three more Freewheelin’ outtakes, all from the final session of 1962 (there will be one more the following April, from which we’ll hear a couple never-circulated tracks on the next disc). “Whatcha Gonna Do?” is another in the category I’m calling original-but-sounds-like-a-cover. Dylan ably imitates an old gospel-blues song, in the Robert Johnson vein of death and the devil, without bringing anything wildly original to it. It reminds me of a cover he might have played in one of those early Gaslight or Gerde’s tapes. Not a major loss leaving it off the album, but a fun, if slight, listen.

We stay in the blues genre with “Hero Blues.” Those who read my 1974 series last year will remember this song kicked off Dylan’s comeback tour with The Band. That was a wild electric arrangement, only played twice. This is, needless to say, a lot quieter—and less memorable. It’s got some funny lines (“You need a different kind of man, babe / You need Napoleon Bonaparte”) but is musically a bit generic. What’s wild is, after leaving it off Freewheelin’, he apparently seriously considered putting this on The Times instead of (the infinitely superior) “One Too Many Mornings.” Here’s the ’74 version:

Disc four, and our 1962 selection, concludes with “I Shall Be Free.” Finally, another song that actually was included on Freewheelin’! This is a different take from the same day. Notable, this version is almost two minutes shorter than the Freewheelin’ one, fading out before the final verses (don’t worry, it still has the boner joke).

I’m not sure why they fade it out early here. My guess is maybe it fell apart; he slips up on a few words of the last verse we hear, though recovers. He’s supposed to sing “Oh, there ain’t no use in me working all the time” but instead sings “working so hard.” Which screws up the intended rhyme (“I got a woman who works herself blind”), as you can hear him realize in the moment. So he wings it, stumbling about a bit and landing on “I got a woman…in a…coffeehouse yard” to keep the rhyme. Which doesn’t make any sense (in a what?), but is fun to hear him try to salvage the slipup.

DISC 5

Never-circulated-before tracks marked with *

1. THE BALLAD OF THE GLIDING SWAN

Broadcast January 13, 1963 – “Madhouse on Castle Street,” BBC-TV Studios, London, England

When I interviewed British folk great Martin Carthy, he remembered visiting Dylan in late 1962 when he was filming the BBC teleplay Madhouse on Castle Street. Here’s a bit from my conversation with Carthy:

What do you remember about that play? The recording that aired on TV with Dylan in it seems to have been lost.

The BBC deleted it. Stupid bastards. They had a big clear-out at one point, and one of the plays that was cleared out was this.

I read you were there for the filming of some of that play.

I was, oh yes. I’d go in regularly. I found the songs that he was singing hilarious. One song he had to sing [“Ballad of the Gliding Swan”], he changed the words: “Lady Margaret’s belly is wet with tears / Nobody’s been on it for 27 years.”

He’s right. The BBC did delete it. Madhouse on Castle Street is one of the great pieces of lost Dylan media.

I was hoping Sony might have magically unearthed the complete “Ballad of the Gliding Swan,” but alas, it’s the same minute-long fragment that’s already circulated. Though perhaps it faded out in the actual TV broadcast as well. It certainly sounds like Dylan intends to keep going. Dylan supposedly wrote this song specifically for the play. The play’s director, Philip Saville, recalled to Radio Times in 2005:

He turned up to our first read-through. His first lines were half a page of his character’s beliefs about what’s wrong with the world. But Bob went silent, and said ‘I can’t say this stuff. I’m not an actor, and you’re all great actors.’ So we got David Warner to play the main role, while we retained Bob to read a poem [sic], ‘Ballad of the Gliding Swan,’ and to sing ‘Blowin’ in the Wind.’ Tragically the tape was destroyed in 1968, as was footage I took of Bob shopping in Carnaby Street. I remember him saying, ‘Why don’t you give up this life’ - meaning I was a family man - ‘and come on the road with me, that’s what life’s about.’ I half wish I had at the time!

It would be huge news if anyone turned up a video, but, given that the BBC deleted it and this was a long time before home-recording VCRs, that seems unlikely to ever happen.

2. ONLY A HOBO (Album Version)

3. JOHN BROWN (Album Version)

February 1963 – Broadside Ballads, Vol. 1 sessions, Folkways Studio, NYC

Two songs he gave to the Broadside magazine follow: “Only a Hobo” and “John Brown.” Presumably he’d already decided at this point they wouldn’t be on his own album, so the folk magazine was free to have these topical discards. He was billed as “Blind Boy Grunt,” since he was already under contract with Columbia. I’m surprised the set didn’t include “Talkin’ Devil,” the third song he gave Broadside, on this box set. True, it’s only a minute long (barely even a song, really), but it’s less well-known than these two.

This “Only a Hobo” comes from a six months before the version on the first Bootleg Series, recorded for The Times They Are a-Changin’ (maybe he wasn’t so done with it after all—then he’d revisit it again years later with Happy Traum at the Greatest Hits II sessions). This early version has more spring in its step than the earlier Bootleg Series one. I probably like it better not being so slow, though I miss the harmonica.