A Legal Journalist Remembers Covering the Rolling Thunder Prison Show—And Helping Set 'Hurricane' Free

Plus never-seen photographs from the private event

Flagging Down the Double E’s is an email newsletter exploring Bob Dylan performances throughout history. Some installments are free, some are for paid subscribers only. Sign up here:

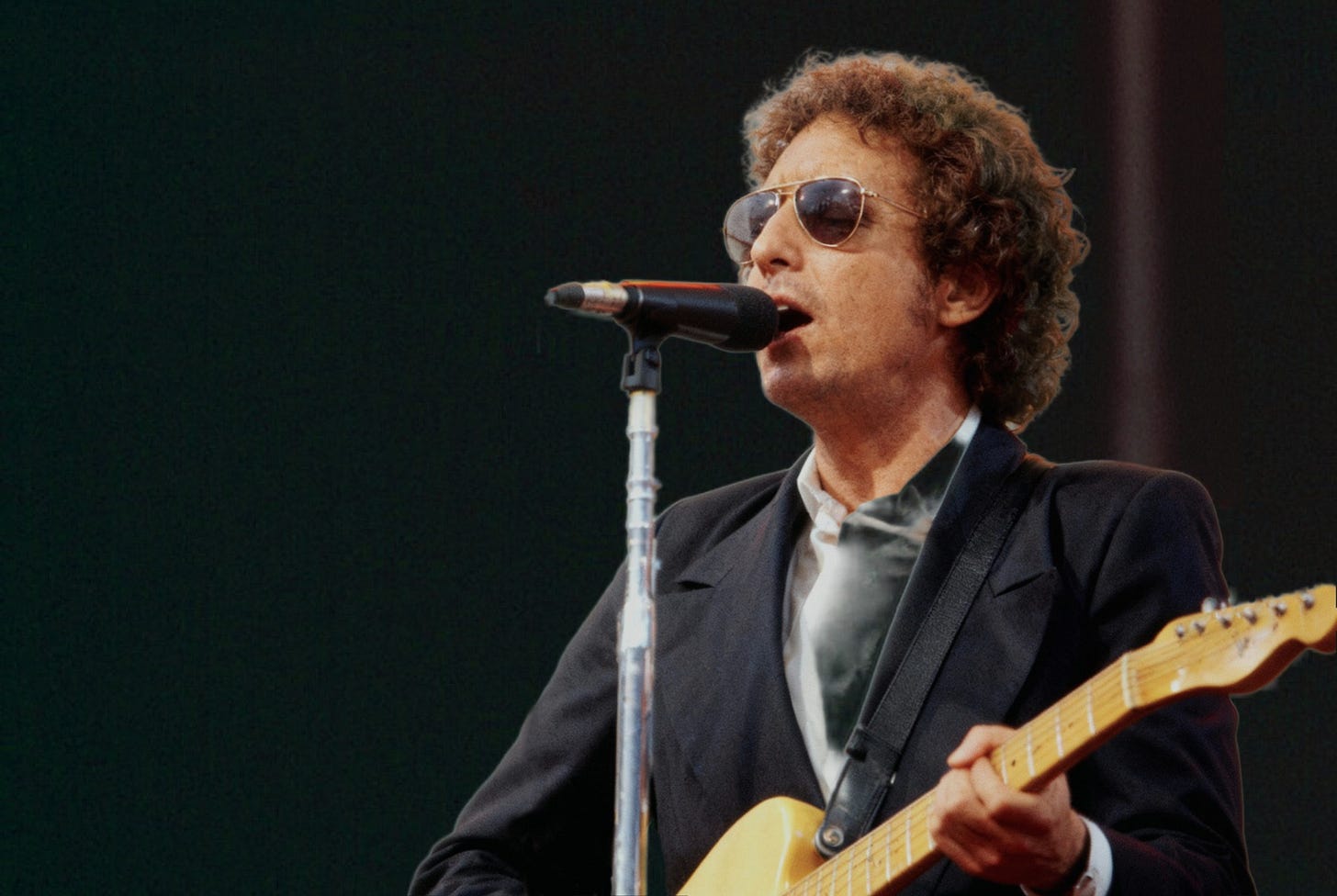

Fifty years ago today, Bob Dylan gave the most unusual performance of the Rolling Thunder Revue. The day before the first leg’s Madison Square Garden finale, Dylan and the full cast—Joan Baez, Joni Mitchell, Roger McGuinn, Allen Ginsberg, etc—performed at a New Jersey prison for Rubin “Hurricane” Carter and other inmates.

The concert was not open to the public, but select media were invited to come cover the event. One young journalist who did just that was Bruce S. Rosen. Rosen brought two different areas of expertise, both as a Dylan fan and as a professional legal reporter. In fact, a decade later, Rosen helped draft the judicial opinion that set Hurricane free.

Rosen shares his story below, along with some never-seen photographs he took at the event.

Remembering Dylan’s Prison Stop Dec. 7 1975

By Bruce S. Rosen

In a way it’s too bad that my greatest rock ‘n’ roll thrill came at age 22, 50 years ago today. While some moments came close, none topped that cold night in a New Jersey prison. During my time as a rock writer, I interviewed dozens of big names and in the past 50-plus years have seen a lot of unbelievable shows, but having the chance to talk to Joni Mitchell, Joan Baez, Robbie Robertson, Allen Ginsberg, Roger McGuinn and others in one room was mind-blowing. Even if seeing Bob Dylan yell at his son for talking to me that night was at least temporarily soul-crushing.

I was a Dylan fan since I first heard “Blowin’ in the Wind” at about 10 years old. I went electric with him in 1965, went country with him in 1969, and was devouring Blood on the Tracks in 1974-75. I had been desperate to see him live but in my high school years he was mostly on his long Woodstock hiatus. That didn’t mean I didn’t regularly scour Greenwich Village looking for any sign of his presence (long after he left) or visit numerous record stores desperate for the latest bootleg. I once responded to a tiny ad in the Village Voice for Dylan’s show at the “Isle of Wight Festival,” and the phone number in the ad turned out to be the Fillmore East concert line where the voice on the recording laughed at callers inquiring about tickets because the concert was off the coast of England. Finally, I was lucky enough to have seen Bob at the Concert for Bangladesh at Madison Square Garden in August 1971 and was floored, then saw him on his tour with the Band in 1974 in the New York area, a bit shouted but fantastic.

Just days after I had graduated Georgetown University in 1975, I returned to central New Jersey, where I grew up, to be a reporter with a daily newspaper then known as the Woodbridge News Tribune. I worked the overnight 7 pm to 3 am shift preparing the paper for its afternoon edition. On about December 5th, I read a blurb in the Newark Star Ledger that Dylan and his Rolling Thunder Revue were going to hold a concert at the Clinton Correctional Facility for Women in Clinton, N.J. It was scheduled one night before a benefit show to be headlined by Muhammad Ali at Madison Square Garden to raise funds for the legal defense of former boxer Rubin “Hurricane” Carter, who was then seeking a new trial for his conviction, along with John Artis, of a triple murder in a bar in Paterson, New Jersey in 1966.

Carter had been transferred to the mostly women’s prison while awaiting word on an appeal seeking a new trial. I had read in the rock press about the many shows created at the last minute by the Rolling Thunder entourage in New England and could not believe it would actually be coming to New Jersey. I read closer. It was not open to the public; only accredited press would be allowed entrance.

Well, by complete happenstance, I had received my New Jersey State Police press card only a week earlier. The concert was to be two days later on Sunday December 7. I plotted with another reporter to attend. The only problem was that I, unlike my buddy, was scheduled to work that night, a Sunday. I was a really dedicated reporter, but a work schedule just wasn’t going to stop me. I didn’t have any editors’ home telephones, so I called the answering machine at work, said this concert was happening and because it involved Carter, whose appeals were a cause célèbre, that I would cover it and come in immediately afterwards. Thus, I literally risked my job to attend (I hadn’t been there long enough to have union protection), but I knew it would be something I would always remember.

Next problem was my camera. I had a single lens reflex, but I was unskilled and I only had one roll of black and white and one of color slide film. Stores were closed. Go with what you got.

I got there in plenty of time for the show. The prison was then 60 years old (it was renamed and had been refurbished over the years before being shut down after a sex abuse scandal a few years ago) and had a large gymnasium with bleachers and a stage, much like a high school gym. It seemed like there were at least 50-75 reporters and plenty of TV cameras. But the press card was all I needed. Once through security, we were met by Lou Kemp, Bob’s boyhood friend who seemed to be in charge of the tour. “Talk to anyone,” he told the gaggle. “Take whatever pictures you want, but don’t go within 10 feet of Bob and don’t take any pictures of him before he goes on stage.” Ok, I wondered, how did Bob get to set the rules at a state prison? Nevertheless, they sounded like reasonable conditions under the circumstances. I didn’t make or hear any objection; the excitement was palpable among the younger reporters even before we walked into the gym. There was the entire Rolling Thunder Revue cast. The interviews began.

If I could talk to anybody, I would talk with everybody. I spent about 15 minutes listening to Joni talk about the The Hissing of Summer Lawns, her jazz-inspired album which had just been released, and Tom Wolfe. I have to admit I was having trouble making sense of some of what she was saying, although I just loved her music. I spent a few minutes listening to Joan Baez hold court talking politics and music. A few words with Allen Ginsberg, a fellow Jerseyan and legend, and a hi to most other band members, including McGuinn and Ramblin’ Jack Elliott and then a few words with Robertson, all of whom couldn’t have been nicer.

At one point I was walking through the gym when a young boy, maybe 8-10 years old, came up to me and didn’t say much more than hello. I said hi back and asked if he’s having fun. Then out of a crowd I see Bob, wearing the trademark Desire hat and scarf, walking toward us. He grabbed the boy by the shoulder and said something along the lines of “I told you not to talk to any of these people, they’re bad people, now go sit with your mother.” He walked away without even looking at me and my gaping jaw. Crushed, soul-shattered. The man himself came over because of something I had done and called me a bad person! I didn’t realize until just then that the kid was his son Jesse, who then walked toward Sara Dylan who was sitting on a folding chair chatting with actress Candice Bergen.

A few minutes later the performers moved toward the stage and the press was told to mount the bleachers to the left of the stage. The 150 or so inmates who decided to attend, mostly women, some dressed in formal wear, sat in rows of folding chairs in front of the stage. The guest of honor, Rubin Carter, was sitting in the front row.

I can’t say I remember the show in detail. It was abbreviated compared to the four-hour Revue shows elsewhere - maybe an hour or so. The problem was the audience. Instead of the usual white middle-class audience, the audience was primarily Black and unfamiliar with Dylan or Rolling Thunder. I do remember Joan and Bob singing “Blowin’,” and later Joan doing the bump with a prisoner onstage to some applause, and then thanking authorities for “making it so easy for us to get in,” and then, appealing to the crowd, said “I just wish they’d make it a bit easier for you to get out.” Joni Mitchell, on the other hand, was actually booed and hooted at when she sang “Coyote,” then started berating the audience for not appreciating the love the group brought to the show. Although the audience seemed unfamiliar with Dylan, the rousing version of “Hurricane” finally created a real reaction. Allen Ginsberg also drew enthusiastic applause for his poem “Kissass,” but truthfully Roberta Flack, who had joined the tour for these Hurricane shows, stole the show and got the standing ovation from the mostly Black audience for the three songs she sang.

Then the performers disappeared. Carter held a brief press conference in front of the stage, and, right before we left, I saw a white young inmate by the stage. Bob came out to sign an autograph for him. No more rules; I had camera in hand and began shooting. Unfortunately, I had slide film in my camera and didn’t adjust my exposure. At least 10 pictures of the white hat from 3-4 feet away were the result; you can barely make out Bob’s face. Ugh.

I did write a short story about the concert for The News Tribune. They didn’t want my pictures so I ended up developing the black and white film myself. What an idiot I am. Got a few good ones, but why did I do that?

Postscript: Almost exactly 10 years later, I had moved on to the Bergen Record and was attending night law school. I covered the federal courts in Newark and was also a stringer for the National Law Journal. I had written a profile of U.S. District Judge H. Lee Sarokin, who invited me to clerk for him and help him write what was to become one of the major decisions of his career as a federal judge: the habeas corpus petition filed by Rubin Carter in 1985. (Carter had earlier won a second trial from the New Jersey Supreme Court and been convicted a second time in 1976. The New Jersey Supreme Court had upheld the conviction by a 4-3 vote in 1982.)

I took a leave from The Record and spent several months drafting the Carter Opinion, which Judge Sarokin then interspersed with some brilliant quotable statements, which made the front page of the New York Times. Judge Sarokin’s decision in November 1985 aligned with the New Jersey Supreme Court dissenters, and he ruled that the prosecution had made an unconstitutional appeal based on racism and had withheld certain evidence. A quote from the decision was the quote of the day in the New York Times, where the decision was front page news. Carter was soon freed after serving 17 years (Artis had been released earlier). The decision was upheld by the Third Circuit Court of Appeals. Carter lived out the rest of his life near Toronto (he died in 2014), advocating for the unjustly accused and on a few occasions speaking about habeas corpus at legal conferences with Judge Sarokin, who died in 2023.

I saw the film Hurricane and frankly what happened in real life was more dramatic than the condensed film version starring Rod Steiger as the judge (the real judge was screen tested for the role). I personally released the decision after I let the media and parties know it was coming. Only Carter’s lawyer showed up for a copy. The prosecution was so confident they would win that they sent a detective to pick it up that afternoon only after dozens of media inquiries.

A bail hearing was held the next day and the courtroom was packed. The prosecutors claimed Carter was a danger to society based on statements he had made in a book years before. They begged for more time to present that case. Judge Sarokin said he’d think on it for a few minutes and asked me to come back to his chambers and discuss it. He said, “OK, pretend you are the judge, what would you do?” I said I’d give prosecutors 48 hours to find real evidence and then hold another hearing and probably let him go. The judge said no. He put his neck on the line with a decision he believed in: He was going to let him go. When he announced his decision a few minutes later, the huge WPA-built courtroom exploded into pandemonium. Carter, dressed in his sheepskin coat, held a brief press conference on the courthouse steps. Carter never went back to jail.

I later wrote and edited legal publications and became a full-time lawyer some years after, focusing on First Amendment issues. My home office is a Dylan museum with signed photos, lithograph, books and a huge signed Daniel Kramer photograph of Bob and Joan posing along next to a gin ad on the walls of the old Newark Airport that read “Don’t Be a Conformist,” alongside photographs I took years ago of Bruce Springsteen, Pete Townshend and signed Jerry Garcia artwork. Since becoming a parent and grandparent, it has become clear to me over the years that while the younger press in attendance were far more reverential than being “bad people,” Bob may have been right in protecting his child, despite crushing my 22-year-old heart that night. Amazingly, that did not ruin the memory for me.

Thanks to Bruce S. Rosen for taking the time to tell his story and share his photos! Rosen is currently a Partner at Pashman Stein Walder Hayden, P.C. in New Jersey.

I cannot get enough of these posts/entires. I stumbled on to bits of magic. Thank you!

HI, After Rubin got out and moved to Canada in fear of the US gov. doing yet another nasty deal and him ending back in prison, i got to know him somewhat and photographed him numerous times, had some great life changing conversations and feel honoured to have known him. A photo with Vern Harper who was also a boxer in his early years called Hurricane Harper after his hero Rubin at the time. Vern a cree medicine man and Rubin became close friends, both gone now....rubin and vern (i have many other photos of Rubin)

https://patrickwey.com/p452074209/ea4d1149e