Roger McGuinn Talks 50 Years of Rolling Thunder

Plus The Byrds, Tom Petty, Bobfest, and the rest of his time with Bob Dylan

Flagging Down the Double E’s is an email newsletter exploring Bob Dylan performances throughout history. Some installments are free, some are for paid subscribers only. Sign up here:

Fifty years ago today, Bob Dylan launched the Rolling Thunder Revue. Along for the ride every step of the way was Roger McGuinn.

Dylan and McGuinn already had a long history by then, of course. Way back in 1965, The Byrds made “Mr. Tambourine Man” a number-one hit. Dylan praised them in interviews, telling the Los Angeles Free Press, “They’re doing something really new now. It’s like a danceable Bach sound. Like Bells of Rhymney. They’re cutting across all kinds of barriers which most people who sing aren’t even hip to. They know it all.”

Earlier this year, I spoke with McGuinn for a career-spanning conversation about his work with Dylan. We started in the ’60s, of course, then continued into Rolling Thunder, McGuinn’s ’80s stint as the opening act for the second Dylan-Petty tour, and beyond. Here’s my chat with Roger McGuinn:

I was just watching Dylan at the Newport Folk Festival when he did “Mr. Tambourine Man.” As you know, I’d done it like— [plays the famous opening guitar riff] I’m going from the D to a G. I was watching his fingers, and he’s doing an E minor 6 instead of a G. He’s like [playing and singing] “Hey, Mr. Tambourine Man, play a song for me.” That’s an E minor 6, but not a G. I got it wrong.

All these years later, you just realized that?

Yeah, like 50-some years later. I did that with “My Back Pages,” because I learned it off a record. I just got it phonetically; I never saw it in print or anything. He says some things that I didn’t say, like “Crimson flames tied through my ears, rolling high and mighty traps.” I thought it was “flowing high and mighty traps.” Then he says “pounced with fire,” and I said something else [“countless fire”]. Then I thought it was “romantic flanks of musketeers,” and he sings “romantic facts.” I’ve been singing it wrong all my life.

Well in some cases, including “Tambourine Man,” you’re recording them before there’s even a record out. It’s not like you can study the Dylan album 100 times.

I didn’t know it until I looked at the YouTube video, and I watched his fingers.

Since we’re already talking that era anyway, let’s go back to the beginning. Do you remember the first time you heard Dylan’s music or became aware of him?

It was at the hootenanny at Gerde’s Folk City. In ’61, I guess, somewhere around there. I knew him when he got to the Village. He was around.

Were you already in New York by the time he got there?

Yeah. I’d been working with the Chad Mitchell Trio prior to that night. I got an apartment in the Village with Mike Settle. I never spent any time there; I was traveling a lot. I had another house in Laurel Canyon, up in Wonderland Drive. Art Podell and I were roommates up there. Art was in The New Christy Minstrels.

What, if anything, do you remember about that Gerde’s experience?

Cisco Houston and the other folk singers would get up there and play a couple of folk songs, and everybody clapped, and that was it. But when Bob got up there, the girls tittered and squealed. Like he was a rock star, back then.

Even before anyone knew who he was.

Yeah. He had a certain charismatic appeal to the females.

When they cast Chalamet in the movie, I remember there was some debate about, “Oh, he’s too conventionally movie-star attractive.” Other people were saying he captures that charisma and the thing you’re saying with the girls.

I think he was really good. You know what? He fingerpicked, and Bob didn’t do that.

I saw a recent tweet where you were, I don’t know if miffed is the word, but you were at least commenting on The Byrds not being included in that movie.

Yeah, but I think that’s irrelevant because it ended up at Newport, and The Byrds didn’t really play a part [there].

Did you overlap a lot in the Village scene during your couple of years there?

I hung out at Gerde’s Folk City. I used to watch the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem. Bob Gibson was around. Bill Cosby and Woody Allen. I think Peter Yarrow was solo at that point. It was a cool scene. Only by a couple of years, I missed the Kerouac scene. I’d love to have been part of that. Bob, when he got to be friends with [plays guitar] the Beat people, it was really cool. Allen Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky and those guys.

Figures who will return in the Rolling Thunder era as the baggage handlers. [Ronee Blakley: “Allen and Peter Orlovsky, his partner, acted as baggage handlers. We’d put our bags outside our hotel door and they would come and pick them up. It was wonderfully strange.”]

Yeah. Bob was trying to recreate the Village on purpose.

Do you actually meet him back then?

I said hi to him. I didn’t know him.

Is the first time you really meet properly out in LA?

Yeah. He came to our rehearsals at World Pacific. We played him some of his songs with my arrangements that were rock and roll as opposed to the 2/ or 3/4-time arrangements that he’d been doing. One of the songs, he said, “What was that?” I said, “That’s one of your songs, man.” He said, “I didn’t recognize it.”

Which song was that?

“All I Really Want To Do.” I put a 4/4 beat to it.

How did he end up at that rehearsal?

He knew Jim Dickson, who is the guy who let us record for free at World Pacific Studio.

Had Jim brought him there with the explicit purpose of playing you some demos, getting The Byrds to record them?

Bob had recorded “Mr. Tambourine Man,” but he didn’t release it because Ramblin’ Jack Elliott was on the session. He’d had a little too much to drink and was singing out of tune. Bob is not one to go back and redo stuff in the studio, so he just left it as a demo. Witmark & Sons, his publishing company at the time, was trying to sell his songs. They sent the demo of “Mr. Tambourine Man” out to California. That’s where we first heard it.

Did you hear it as a Byrds song immediately, or did you take any convincing?

Jim Dickson was in love with the song. He just thought it was the greatest song. David Crosby hated it.

We played this demo. It was 2/4 time, four-and-a-half-minutes long, and radio wouldn’t touch anything over two and a half minutes. They weren’t playing a lot of 2/4 stuff anymore. They were playing rock and roll like The Beatles and The Stones, 4/4 time.

That famous “Tambourine Man” guitar lick, is it something you struggled over, or did it come in an instant?

It came right away. It’s part of the melody of the song, but it’s also in— [plays Bach’s “Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring” on guitar]. I’d been playing that. I learned that from Pete Seeger on his Goofing-Off Suite. He did it on banjo.

McGuinn demonstrates how “Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring” becomes “Mr. Tambourine Man”:

See? It’s in there.

The Byrds in those days covered a ton of Dylan songs, too many to go through one by one, but what were you looking for in a Dylan song to put your stamp on? What made a Dylan song a good candidate for the Byrds?

Well, we appreciated Dylan’s sense of lyrics, that his lyrics were deeper than “Be my baby.” It was poetry, and it elevated rock and roll to another level.

I remember I met The Beatles, and George told me, “We just had this big fight with Bob Dylan.” I said, “What was that?” “[Bob] said, ‘Well, you guys are just writing these songs that don’t make any sense. They’re just bubblegum. Why don’t you put some meaning into your songs?’” And they started doing that after he told them that.

You mentioned Crosby disliking “Tambourine Man.” Were you generally the person championing these songs to the band?

Yeah. I became the official Bob Dylan interpreter for The Byrds.

I had to audition for it. Jim Dickson made us read Stanislavski’s An Actor Prepares about method acting, and he made us audition for various parts. To get to sing the Dylan songs, I purposely put a little Bob Dylan and John Lennon vocal together in my head.

What does that mean exactly?

Just the way Bob sang and the way John Lennon sang, which is edgier. I saw a gap between the two of them, so that attitude I was singing “Mr. Tambourine Man” with was consciously trying to channel Bob and John.

Of all the Dylan songs you all did, did you have any personal favorites?

“Positively 4th Street.” I think that’s a great song, but that came later.

When I was listening some of the ones I hadn’t heard in a while, one I loved was “Lay Down Your Weary Tune.”

Bob complimented me on that. I went to visit him at a hotel in LA, and he told me, “I thought you were just an imitator, but when I heard you sing ‘Lay Down Your Weary Tune,’ that was really good.”

What’s the story behind that photo on the back of the first Byrds album, of Dylan sitting in for a set?

I think Dickson invited him. He just got up on stage at Ciro’s and played, I think, “You Got Me Running,” the Jimmy Reed song, with us.

Now 60 years later, he’s doing a song about Jimmy Reed every night.

We all liked Jimmy Reed. He was great.

Moving forward a little bit, there’s a few overlaps in between that “Tambourine Man” era and Rolling Thunder, the first of which is the “Ballad of Easy Rider.” How did Dylan end up writing the bridge to that song?

He wrote the first verse and the bridge. Peter Fonda was putting the soundtrack together. I think it was his engineer that put some rock and roll records on there, just as a placekeeper. Then after they listened to it a few times, they got to liking it. It had “Born to Be Wild” and some Byrds songs. But Peter wanted a song custom-written for the movie, so he flew to New York and screened it for Bob. Bob sat in the screening room, wrote down some notes on a cocktail napkin, and gave it to Peter. He said, “Here, give this McGuinn. He’ll know what to do with it.”

So Peter got back on a plane. He flew out to California. He came over to my house, and presented this napkin to me like the Holy Grail. “Bob wants you to have this.”

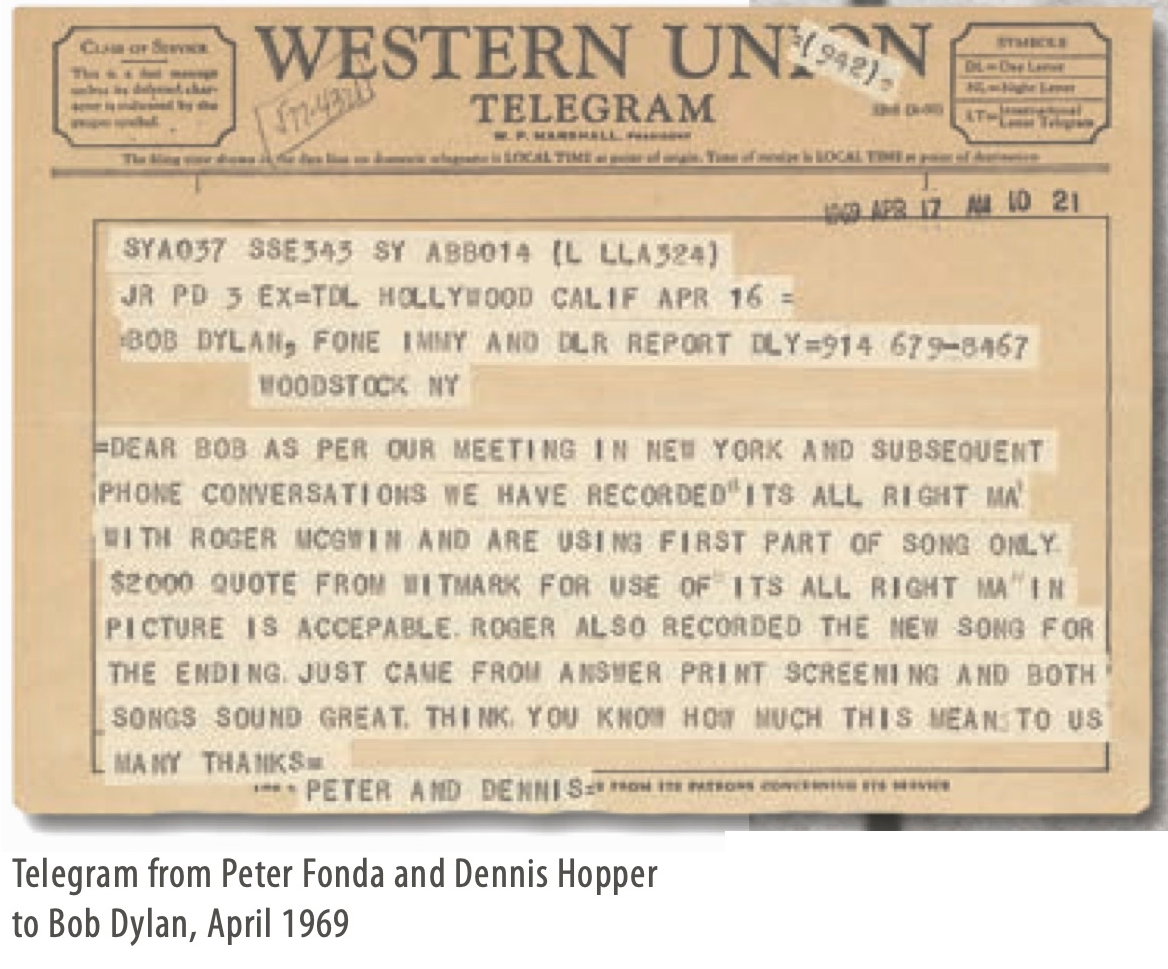

The Dylan Center in Tulsa put out a book a year or two ago, and there’s this great Western Union telegram from Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda to Bob, talking about how they got you to cover “It’s Alright Ma” for the movie.

I saw that. I’ve been to the museum, at least before it was open. It was interesting to look at the paper where he’s handwriting lyrics, and he’d make a little daisy. He’d have a word, and then he’d make like a circular daisy out of synonyms. Like a thesaurus. It was really interesting, because he had all these words to pick from visually. Like, it’d be a line, and then there’d be this daisy of synonyms.

When you say daisy, like petals almost, with some different options?

It was a circle of words that all rhymed with the word that he was trying to think of. So he had a lot of choices. He could look at it and pick and choose what he was going to end up with.

Another thing that precedes Rolling Thunder, there was some plan for The Byrds to back Dylan on a Self Portrait session. It didn’t happen. What went wrong?

Basically, Clive Davis failed to communicate with us about when the session was. My band was sitting in the hotel room going, “What’s going on? Are we going to do this record or what?” Nothing happened for a few days, and then they all flew home. That was the end of that.

You guys are twiddling your thumbs in New York, waiting for a call to do a session, the call doesn’t come. Then by the time the call does come, the guys have already skipped town.

Yeah. I was looking forward to it. I was ready to do it. Wasn’t like we were trying to diss Bob and not do it because we didn’t like it.

Did any part of you feel like you dodged a bullet when that record came out and was universally derided?

No. I was sorry it didn’t work out.

I interviewed Happy Traum before he passed. He was talking about the stuff he did for the Greatest Hits II sessions, including Dylan’s rewritten version of “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere,” which draws from The Byrds’ cover, but now includes that line about you [“Pack up your money, pull up your tent, McGuinn”]. How did you take that? Is it a dig?

What happened was, on the verse, I turned around what he wrote. I got it backwards. He [originally] wrote, “Pick up your money and pack up your tent.” If you listen to The Byrds’ version, I sang, “Pack up your money and pick up your tent.” Bob doesn’t like you to mess with his lyrics. It was a friendly jab.

I also interviewed Jim Keltner about the Pat Garrett sessions. He talked about playing along to the film being projected on the wall, and how moving it was recording “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door” to that. You were on that session too. What do you remember?

They have an actual film screen that they put the picture up on. There’s a green line where you start, and another line where you stop. It’s recorded on magnetic film, which has sprockets on it.

Bob and I were hanging out together in Malibu. He would come over to my house. I actually drove him down to the studio that day with my Rickenbacker. It was a really cool session. I thought the song was so appropriate for the part of the movie. I really had a good time with that session. I played banjo on it, too. I did the “Turkey Chase.” There’s some Scruggs banjo stuff that I did.

Around that same time, on your own song “I’m So Restless,” Dylan’s on harmonica. Is this related to the Pat Garrett sessions somehow?

No. He came to my studio. I was working at Wally Heider in LA, and he showed up. I was producing it myself, and he wanted to see how that went. Maybe he wanted to produce himself. I had to talk him into playing harmonica. I wanted him to be on the record. He said, “You do it. You play the harmonica.” I said, “I’d really like you to do it.” He finally did.

Why did you want to produce yourself at that point?

I wanted to have control. Now, the album was not commercially successful, but some people liked it. In fact, Elvis Costello licensed it and put it out on a label some years ago.

A second life.

It’s very eclectic. I wasn’t really trying to get a hit. I was just doing all the things that I like, like sea shanties and blues and whatever.

It’s got the airplane song, “Draggin’ ‘cross the USA.” I gotta tell you a funny story about that. “Draggin’” is two 747s having a drag race across the country right? Jacques Levy and I wrote that. I went to the Astronauts Hall of Fame a few times, and I played it for the astronauts. One of them came up to me and said, “We used to do that!” They used to drag race their planes across the country.

Since you mentioned him, and he will play a big role in Rolling Thunder, how did you first connect with Jacques Levy?

I was playing the Fillmore East and this really attractive blonde lady came backstage and said, “My boyfriend would like you to help him write the score to a Broadway musical.” I said, “Okay…”

Then he came back. You can see why he sent his girlfriend in first, because he’s a big burly guy. I might not have said yes right away.

Is the girlfriend Claudia? I interviewed her too. She was just talking about your friendship and how close you and Jacques were.

It was before Claudia. Yes, we had a lot of fun together. Did you ever listen to the guys from Boston who had the car show and they just laughed all the time [Car Talk]? Jacques and I were like that. Every other sentence was a laugh.

Jacques and I wrote songs for that play, about 27 songs, and it didn’t get mounted on Broadway. We couldn’t get funding. So I recorded a lot of the songs on Byrds records. I’m still working on versions of the songs, re-recording them myself. I’m going to put ‘em out somewhere sometime.

Is that play the origin of “Chestnut Mare” and “Lover of the Bayou” and some of those songs you would play on Rolling Thunder?

That’s right. There are some that haven’t surfaced, like “The Robbing of the Stage.” There’s a gospel song: “Are you right with God? Yes I am.” We got some material here that hasn’t been exposed to the public yet.

Anyway, Jacques and I were writing partners. He called it his other career. He was doing Broadway, and he’d come out to LA and come over my house in Malibu, and we’d write for a couple of weeks. Then he’d go back, and I’d have another record’s worth of songs.

Bob would come over. One time, he saw a basketball hoop over my carport, and he asked me if I had a basketball. I didn’t because when I was 15, I jammed my finger on a basketball. I couldn’t play guitar for a few weeks, so I wasn’t really big on basketball. The next day, I went out to the sporting goods store, and I bought a basketball. I called up Bob’s house in Malibu. Sara answered; Bob was out. I said, “Tell Bob I got a basketball.” She said, “Oh, he’ll be thrilled!” I was like, “Really?” [laughs]

He came over, and we were shooting baskets in the backyard. He’s pretty good. He said, “I want to do something different.” Now, Bob saying he wants to do something different is like, let’s strap rockets to our back and fly to Mars. I said, “What do you mean?” He said, “I don’t know, something like a circus.” That turned out to be the Rolling Thunder Revue.

A few weeks later, I was hanging out in the Village, and I ran into Larry Sloman. Ratso. At the time, he was a reporter for Rolling Stone. He said, “I think Bob’s over at The Other End.” We went over there. There was nobody at the bar, but there was a little dark room in the back, and Jacques Levy and Bob were having a couple of brandies at a table. I walked in, and they both stood up and went, “Roger, we were just talking about you!” The brandies went flying like in an old Western movie. They said, “We’re putting this tour together. We’d like you to go on it.” I said, “Oh, man, I got dates booked with my band.”

The next day, I called my agent and postponed those dates and went on the Rolling Thunder tour.

How did you land on “Knockin’” as the big finale duet you two would do together?

Jacques Levy put all those things together. He directed who would come out first, like Bobby Neuwirth, and then Bob and Bobby would do some stuff, and then Ronee Blakley would come out or something. He orchestrated the whole thing. It was like a circus. Everybody was painted up like clowns and wearing costumes.

Was he involved in choosing the songs you did in your own sets? A lot of those are Jacques co-writes: “Chestnut Mare,” “Lover of the Bayou.” You did “Eight Miles High” some too.

Yeah. He was musical director for the whole thing, so he did orchestrate those. We wrote a song, the “Jolly Roger,” because Bob had borrowed a bus from Frank Zappa that was called Phydeaux. It creeped back and forth like a pirate ship. Jacques and I decided to write “Jolly Roger” to capture that spirit.

McGuinn playing “Jolly Roger” on Rolling Thunder:

Everyone talks about that bus. Everyone always brings up Phydeaux.

It was fun. It had a bedroom in the back and bunks for the band in the middle and couches up front. I remember Joni Mitchell used to sit up front, looking out the window and writing songs. She had a composition book full of new songs. I asked her for a song, ‘cause I needed one for an album I was about to do, and she gave me “Dreamland.” It had a line in it, “I wrapped their flag around me like a Dorothy Lamour sarong.” I changed Dorothy Lamour to Errol Flynn.

Speaking of Joni, one of the iconic videos from the movie is “Coyote.” It’s basically just you, Joni, and Bob playing a brand-new song she had written.

It was at Gordon Lightfoot’s house in Toronto. We were jamming and drinking beer and having a good time. Joni had written a song about Sam Shepard, whom she had just a brief affair with. It was a lot of fun.

Speaking of parties in Canada, I read reference to a dinner at Leonard Cohen’s house in Montreal.

It was a very small house, and he was all dressed up with a jacket and tie. He served us sake. Joni and Leonard got into this abstract discussion about creativity. Joni was into this thing about, I don’t know, music and colors. She would have to tell you what she was saying, but she and Leonard seemed to be on the same frequency with it. It lasted a long time.

Someone I interviewed from the tour mentioned that you were carting around what he described as one of the first cell phones. It was like the size of a briefcase, he said.

Yes, a briefcase telephone. It was invented for the CIA and those guys. It’s like a spy tool. It had a handset, almost like a princess phone or something. It weighed about 20 pounds. It was a 25-Watt FM transmitter that worked on 12 rechargeable D cells batteries. I still have it. They disconnected the frequencies, but it still would work if the tower was still on those frequencies.

How did you end up getting a CIA telephone?

I’m a gadget freak, and I just found out about it and bought it. It was like $3,000, which was some real money back then. I loved it. It was one of my favorite gadgets.

On that first part of the tour, any shows in particular that stick out all these years later?

The Halloween show where Bob was wearing that translucent mask. That was a good one.

They were all good. He was in top form. He was just really on fire out there on stage. He was singing great, and he was emotionally involved. He was really punching every lyric. It was incredible. The best I’ve ever seen him, really.

The first few shows were in small theaters, like several hundred people, not more than 1,000 at the most. I remember one time I was dressed up like a riverboat gambler. I had a deck of cards, and I’d throw it out into the audience. One time, I threw it out, and I had a bracelet. It was a handmade thing from a Zuni Indian. It was silver and precious stones, like a thousand dollars. I threw the cards out, and the bracelet went flying with them. I said, “Oh man…” Nobody returned it. Somebody got a souvenir that night. I said, “Well, it was in the cards.”

I live in Burlington, Vermont, and you played four blocks from where I’m sitting right now. I think it was a gym in this case, not a theater, but a tiny place.

The first half was all small venues, and then Bob needed to make some money, so we started playing stadiums after that. It wasn’t as much fun.

I remember Willie Nelson was on one of them in the big stadiums in Texas. I didn’t know who Willie Nelson was at the time. I don’t think he knew me either, because we’re both on the same mic in the middle of the stage looking at each other like, “Who are you?”

Pretty much everyone I’ve talked to in the band describes the second half as musically great, but less fun off stage.

There was less camaraderie. First part, we were all hanging out and loving each other, and it was like a big family. The second half was more like a commercial tour.

The one moment of camaraderie everyone tells me from the second leg is the alligator barbecue at Bobby Charles’s place in the bayou.

Oh yeah! He had a keg of beer and he had a cooked alligator in aluminum foil and no plates or utensils or anything. You go and take a handful of alligator, put it in your mouth, and chase it with a beer. It was great.

One story Claudia told me about you happened at a show in New Orleans, you calming a restless crowd. “Jacques didn’t ruffle. He was not a man who lost his temper or raised his voice. He knew that if you had to counter any kind of restiveness, you send out Roger McGuinn. Jacques said, ‘Okay, Roger, hit the beaches.’ Roger went out and started playing ‘Eight Miles High.’ That did the trick.”

I don’t remember that specifically, but Jacques was very calm. I miss him. We had a lot of fun together. I went to see him in the hospital the day he died. I bought my guitar and I was singing songs to him. He was in a medically induced coma. I started singing one of his songs and he started smiling. In a coma.

Then they took him out of it, and I sang till my fingers were almost bleeding. Jacques was a prankster; he was always trying to get you. He wanted me to play “Sweet Mary,” a song that he and I had written about one of his old girlfriends. I couldn’t remember it. My wife said, “He got you from his deathbed!”

He died that day. We got back to the hotel, and we looked out the window, and there was this whole flight of black balloons that went flying up. My wife said, “There goes Jacques.”

Was he at every Rolling Thunder show?

Oh yeah. He was in charge. He was like the headman. He told Bob what to do.

As things come to an end, the big show everyone remembers from that second round is Hard Rain out in Colorado. What do you remember from that one?

It wasn’t my favorite show. It was cold and rainy and 5,000 feet and we couldn’t breathe.

David Mansfield said his fingers were getting numb while he’s trying to play pedal steel. It’s an iconic show from a fan’s perspective, but it sounds miserable for all of you.

It was not a good experience to be playing in a cold rainy day outside. I’m not sure what the elevation of Fort Collins is. I think it’s even higher than Denver.

I wanted to ask a couple of other Rolling Thunder things before we move on. You mentioned Ratso before, and one moment in his book I wanted to ask if you remembered because it made me laugh. He wrote, “An obviously well-fueled Roger McGuinn kept goading Dylan to sing his new Joey Gallo song by breaking into the ‘Joooey’ chorus acapella every chance he got.”

I think I was too fueled to remember that. [laughs]

There’s that famous video that closes the Scorsese documentary of you and Dylan doing “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door” together. You both look crazed, and I mean that in the best possible way, but I was wondering how much of that was adrenaline and how much was…something else?

We were play-acting. That was part of that whole circus environment that Bob wanted to capture. I loved that he is doing knock-knock-knocking with his hand, and his eyes are open wide, and so are mine. It looks like a couple of nuts.

That was just theater on your part? That wasn’t chemical enhancement?

Yeah, it was theater. We weren’t really that crazy. We were putting it on.

Any other memorable moments from Rolling Thunder, either the first or the second legs of it?

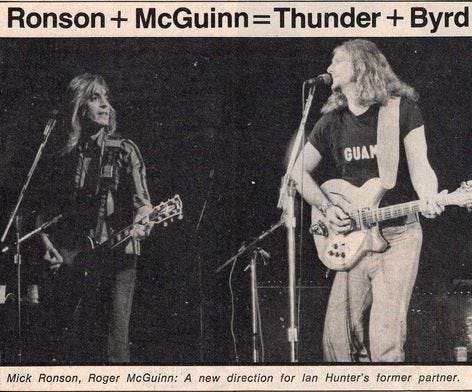

Mick Ronson and I hung out a lot. They always had a hospitality room, which had all kinds of drinks in it. We’d end up there every day.

There’s a great photo of you and Mick playing together. The caption says, “McGuinn + Mick = Thunderbyrd.” You’re wearing a T-shirt that says Guam.

Guam was the name of the band in Rolling Thunder. My wife found the t-shirt after we got married. She said, “What’s with this Guam t-shirt?” I said, “That was the name of the band. We named it Guam because nobody had ever been there.” She said, “I used to live there.”

Was the shirt something that the band members made?

Yeah. We had them printed up.

Do you still have yours?

No. I sent it out for dry cleaning. It never came back.

It’s like that bracelet. People getting souvenirs.

Can’t hold onto everything. Still have the briefcase telephone.

Right after Rolling Thunder you did the Cardiff Rose album, which feels to me like it’s Rolling Thunder minus Bob.

Right. It’s the Guam band with Stoner and Mick Ronson and Howie Wyeth and those guys. It was a very, very energetic band. Some of the tracks are incredible, like “Dreamland.”

Plus of course, one Dylan track, the unreleased Blood on the Tracks outtake “Up to Me.” First time anyone heard it. How did you end up with that one?

He gave it to me. I asked Joni for a song and she gave me “Dreamland.” I asked Bob for a song, and I got “Up to Me.” I did it in his style on purpose. I did “Dreamland” trying to sing like Joni. Nobody really got that, that I was doing the people who wrote it. I was trying to emulate them.

Then on your next album, you do “Golden Loom,” another never-heard Dylan outtake, this one from Desire.

I love that song. To me, that’s my favorite Dylan album. I just love the songs on that, I guess because of the association with Rolling Thunder and the nostalgia of it.

Were you around at all when Bob and Jacques were writing those songs together or recording Desire, or was that before you got aboard?

They were hanging out in New York before I got there. I was on tour with my band. I used to live in the Village and I decided to spend some time off there, and that’s when I bumped into Larry Sloman. They had already been writing songs at that point.

Were you surprised to learn that Jacques had written all these songs with Dylan?

I didn’t know anything about it. I guess they bumped into each other at the Bitter End and decided to do that. There was a bar next door called The Dugout. They used to hang out there.

Moving on from Rolling Thunder, the next public appearance you make with Dylan is at the Warfield in 1980 on “Mr. Tambourine Man,” but there’s a few years in between. In the late '70s, he and you both find Christianity. Are you in touch during that period?

I wasn’t in touch with Bob during that period after he became a Christian. I think his girlfriend, Mary Alice, got him into it. That guy Larry [Myers], who was a Baptist preacher or something, invited Bob and me to his house. We were there, but we didn’t really communicate very well. It was a strange feeling.

So you weren’t part of the Vineyard Church circle with T Bone [Burnett] and [Steven] Soles and that whole crew with Dylan becoming born again?

No. I find it interesting that so many people from Rolling Thunder did accept Jesus.

Bob has always been on a religious quest. I think that might have something to do with it. When I sang “Mr. Tambourine Man,” I was singing to God. God was “Mr. Tambourine Man.” “Take me for a trip on your magic swirling ship”—that’s the earth. “My hands can’t feel to grip. My toes too numb to step”—it’s like submission.

I was listening to a bootleg of that Warfield sit-in. Bob and the band are clearly playing The Byrds’ arrangement, which they don’t usually.

Same thing happened at BobFest with “My Back Pages.” That was my arrangement of that, because the original had been in 3/4 time. I put the rock beat to it.

There’s some rehearsal footage where you’re huddling with Harrison and Petty, walking them through the song.

George asked me the phrasing on the verse that he was going to do, and I showed it to him.

I told you I got the words wrong. They had teleprompters at the foot of the stage for people who didn’t know the lyrics like I thought I did. I’m looking at these official Bob Dylan lyrics scrolling up the teleprompter, and they’re different from what I’ve been singing. “Romantic facts of musketeers” instead of “romantic flanks.”

Was that your first realization?

Yeah. I’d never seen it in print before. I just learned it off the record, and I did it from memory every time.

So which version did you sing at Bobfest, the one in your head or the one on the teleprompters?

The one in my head. I’ve been doing it wrong 56 years.

Why change now?

A funny anecdote. This is at soundcheck. Clapton went out and did a really wonderful version of whatever it was he was doing. He got off stage and Bob said, “Hey man, you can either sing great or you can play great, but you can’t do both at the same time.”

He was just teasing him.

To backtrack a little bit, one of my favorite eras ever is the two Heartbreakers tours in the '80s. You were on the European run in Fall 1987.

What happened was my wife and I went to see Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers in the sports arena in Tampa somewhere in '87. We were sitting in the arena and people were throwing frisbees. One of them sailed down and hit Camilla in the eye. It wasn’t serious, but the usher saw it and thought somebody ought to take a look. There was a doctor backstage.

Just as we were going back, Tom and the Heartbreakers were getting off their bus, going to the dressing room. Tom saw me in the hall and he said, “Roger, you got to come up and do some songs with me.” I was wearing white shorts and a red Hawaiian shirt. It looked more like I was going to a Beach Boys concert. I got up and did a couple songs with him anyway.

The next day he invited us out to the Don CeSar Hotel on St. Pete Beach. His daughters were quite young and we were flying kites. He casually mentioned, “In a couple of weeks, I’m going to tour Europe with Bob Dylan.” I said, “Oh, man, you’re going to have so much fun,” because I remembered the Rolling Thunder tour. I told him about that. He said, “I’ll ask Bob if you can come along.”

He called up the next day. He said, “I talked to Bob. He said, ‘Bring him along. He can be the opening act.’”

Really? That’s how it happened?

Yeah, but the way the tour was structured, [Dylan/Petty manager] Elliot Roberts said, “You can come along, but you gotta pay your own expenses.” I was interested in doing the tour, so I did. The Heartbreaks were the house band. They came out and backed me up on a couple of my songs and some Byrds songs. Then they did their set and then they backed up Bob on his. At the end, we all ended up singing “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door.”

We ended the whole tour at the Wembley Arena in London. George Harrison joined us on “Knockin’” for that one.

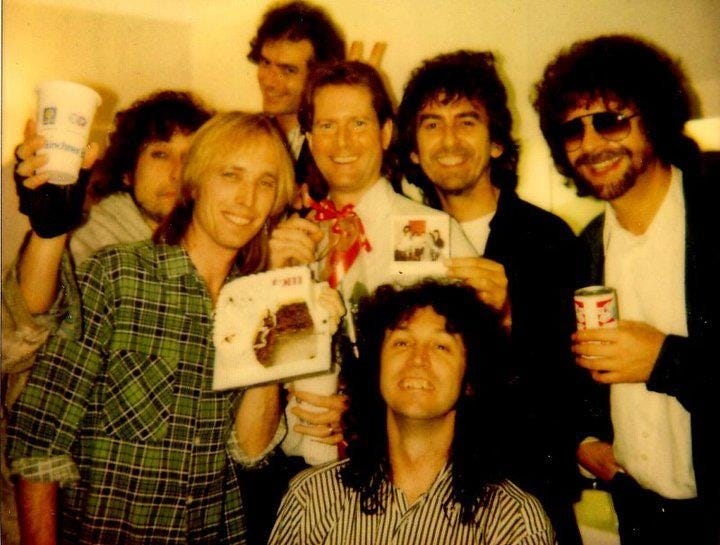

There’s a backstage photo at Wembley where it’s you, Bob, George, Jeff Lynne, Petty. It’s amazing especially in retrospect, because it’s every Wilbury except for Roy. But this is a year before the Wilburys. It seems like it came out of those shows.

George was playing around with the idea of the Wilburys—not necessarily as the band it turned into, but just the name. It was derived from when he and Jeff were recording an album in his home studio. If something was a clam, he’d say, “We’ll bury it in the mix.” That’s where “Wilbury” came from.

One of my favorite memories of the Temples in Flames Tour was we went to East Berlin. That was amazing. We went through Checkpoint Charlie, and they took our passports and kept them for a few days. We couldn’t leave. But we did this outdoor free concert for 100,000 people or so. They all had cigarette lighters and they were lighting ‘em. I was the opening act. I went out there with an acoustic guitar and did “Mr. Tambourine Man.” I think they thought I was Bob, because they all went nuts.

Were you there for the Israel shows?

Yeah. In fact, it was a misunderstanding again. I went out there in Tel Aviv and I was opening up with “My Back Pages,” which I usually open up my own sets. They thought I was an imposter of Bob Dylan. Some guy threw an apple that hit me right in the chest.

If you’re going to play a Bob song on a Bob tour, do you have to run it by him first so you don’t both play “Mr. Tambourine Man,” or does it not matter?

He never told me what to play or sing. Jacques Levy did. Jacques was in charge.

The Heartbreakers must have been playing a lot. They’re doing their own sets. They’re doing this long Dylan thing. They’re doing your set.

I was only doing four or five songs, so it wasn’t that hard on them. They did back me up for a couple, probably “Mr. Tambourine Man” and “Turn! Turn! Turn!”

The Heartbreakers might not exist without those songs, as they’d be the first to say.

I really loved Tom. He was a good friend. I miss him a lot. I used to hang out at his house after his house got burned down and he was in this rented house. George would come over with ukuleles and we’d all hang out. It was pre-Wilburys, but we really had a good time.

You weren’t in the Wilburys, but given that you knew all those guys well, were you following what was going on?

Yeah. I was getting ready to do my Back from Rio album. I was in a rented house in the Hills in LA too, and they were in a rented house recording over there. George invited me over, but I couldn’t make it because I was busy with my own record.

Too bad. Jim [Keltner] said he was a Sidebury. Maybe you could have been a Sidebury too.

They didn’t need me. They had the bases covered. It would have been a lot of fun. I never got to meet Roy. I would’ve liked to have met him. He was with Elvis and Jerry Lee Lewis. A different generation of rock and roll.

Speaking of Roy, that’s the last thing I want to talk about. When I first was getting into Dylan was just pre-YouTube. It was the era of Napster and file sharing and downloading songs that took an hour. For some reason, the first Dylan video I had downloaded in high school was the “Mr. Tambourine Man” in 1990 at the Roy Orbison tribute. It’s The Byrds reunion with Dylan’s surprise appearance. I watched that video a hundred times, because I didn’t have any others.

Bob was supposed to come out earlier, but he didn’t. Then we got to “Mr. Tambourine Man” and he came out and started singing with Crosby. I was going, “Wait a minute, wait a minute. We do this together.” So I went over and got on his mic and we did it almost like Rolling Thunder with “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door.”

There was a moment about a verse into “Tambourine Man” where you look over at Chris Hillman, and you shrug and roll your eyes a little bit. My interpretation of that was always that Bob was supposed to be there already, but god knows where he went.

Exactly. He was backstage. He came out at a good time. It worked out well.

That Roy tribute isn’t what reunited The Byrds though right? It just happened to coincide with when you guys did some new recordings.

That happened because Crosby came over to my house in Malibu. He said, “You know, some of these records you guys are putting out as The Byrds are okay, and some of ‘em aren’t.” I had to agree with him because I’d been allowing guys in the band do their own songs. Some of them were good, and some weren’t.

He said, “What if we all got together and did an album with the original band?” Michael, Gene, Chris, David, and me. I thought, “That might be fun.” We went in the studio with Asylum and recorded that album. David was producing it and so it came out kind of David-centric. It didn’t have a lot of jingle-jangle in it anymore. I think that was too bad. It might have been better.

He made me promise not to do The Byrds without him, and I didn’t. He kept trying to get it back together [later], but I didn’t want to do The Byrds after that.

What overlap have you and Dylan had, say the rest of the '90s and beyond?

One time I was sitting in with Bob in Florida [in 1996] and I was behind him. You know that thing G.E. [Smith] was talking about, he had to look at Bob’s hands to follow along? I couldn’t see his hands. He was doing all these changes, changing time signatures and songs in the middle of the stream, and I didn’t have a clue where he was going. Then he was teasing me. He turned around and said, “Ladies and gentlemen, that’s Roger McGuinn!” And I couldn’t keep up with him. It was embarrassing.

Looking back on all these decades of working together on and off, how would you describe your relationship?

I love him like a brother. Personally, that’s how I feel about him. And I’ve always admired his work. He kind of runs hot and cold with friends. I remember Mike Bloomfield complaining that Bob wouldn’t recognize him at a session. But I’ve always loved the guy and I’ll never change that. I’ve been close to him at times and then not. I don’t think there’s any animosity or anything. It’s just a matter of proximity.

Joan Baez, she was interviewed for a DVD I have. She said, “I remember having dinner with Dylan in Woodstock.” This is 1965. “He’d just about had enough to drink. He is saying, ‘There’s nothing happening in the music scene now. Nothing happening but The Byrds.’” She’s going, “I don’t know if it’s because he liked The Byrds or because they did his song.”

Everyone was doing his songs at that point though. I’d guess it was a compliment.

Yeah, it is. I love him like a brother.

Thanks Roger, and happy 50th anniversary of Rolling Thunder everyone! If you want a deep dive, I wrote a series on every single Rolling Thunder '75 show. Here’s a tape of the first one:

1975-10-30, War Memorial Auditorium, Plymouth, MA

PS. Want more Rolling Thunder? Good news: I’ve interviewed many other participants too. More than any other Dylan tour I think. Click around and find one that interests you:

ROLLING THUNDER MUSICIANS

Cindy Bullens: Guest singer

David Mansfield: Multi-instrumentalist

Gary Burke: Percussionist (1976) - book only

Kinky Friedman: Opening act (1976) - book only

Luther Rix: Percussionist (1975)

Ramblin’ Jack Elliott: Opening act (1975) - book only

Rob Stoner: Bandleader, bassist

Ronee Blakley: Singer, actress

Scarlet Rivera: Violinist

ROLLING THUNDER CREW

Chris O’Dell: Tour Manager

Claudia Levy: Jacques Levy’s wife

David Hendel: Soundman

Janet Maslin: Reviewer

Larry “Ratso” Sloman: Reporter

Louie Kemp: Producer

Mike Evans: “Big Police”

Paul Goldsmith: Cameraman

Rich Nesin: Roadie

Rick Wurpel: Hard Rain concert promoter

Suzi Ronson: Mick Ronson’s wife

Tom Meleck: Designer

Wonderful interview!

Restock the Rolling Thunder zine!

Among many positive qualities of this interview it’ll get me to check out Cardiff Rose. Thank you.