Cameraman Paul Goldsmith Talks Shooting 'Hard Rain' and Rolling Thunder

"You’re standing right next to Bob and Joan. Up close. That’s where my camera is."

Flagging Down the Double E’s is an email newsletter exploring Bob Dylan concerts throughout history. Some installments are free, some are for paid subscribers only. Sign up here:

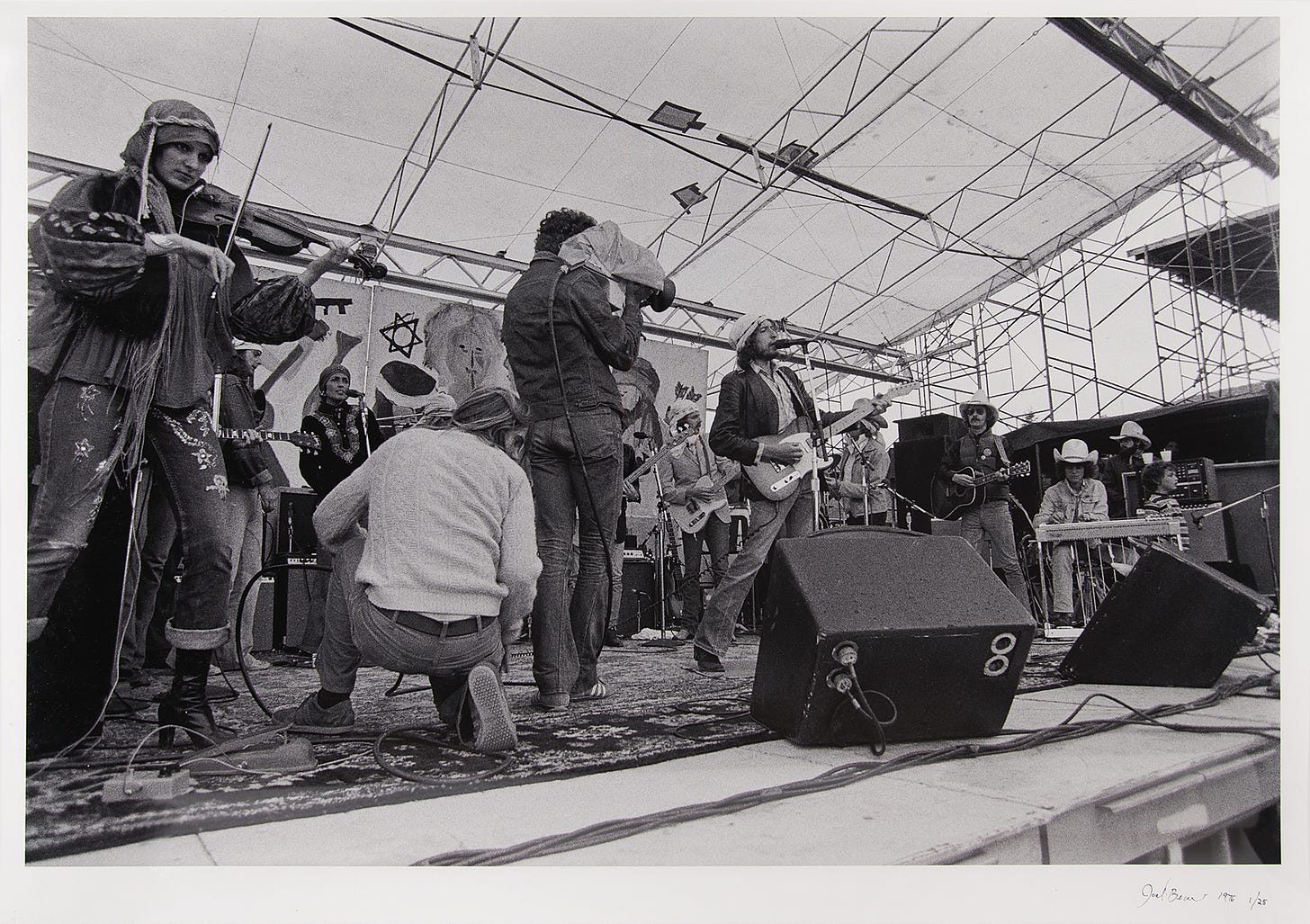

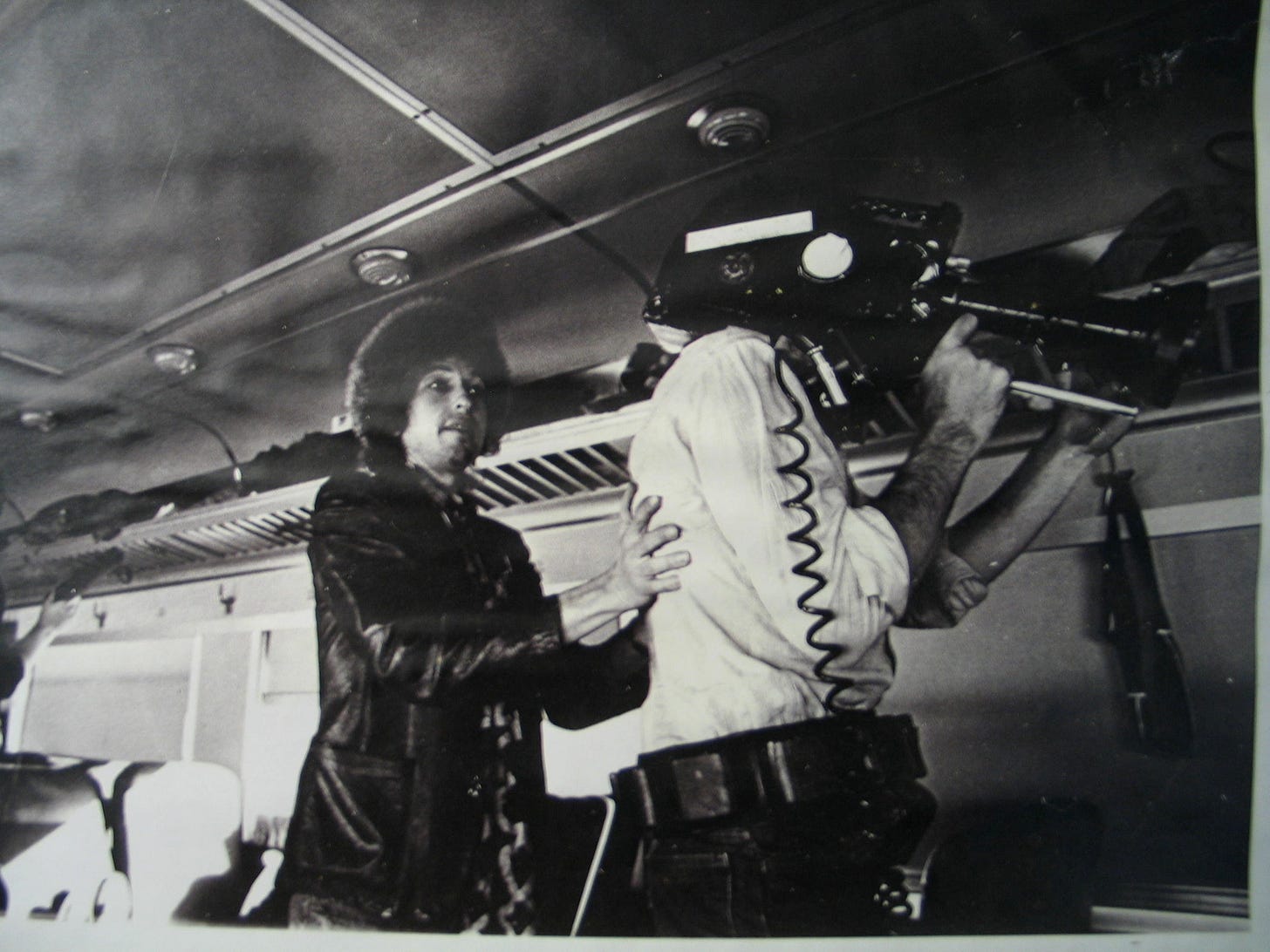

A couple months ago, the above photo went up for auction. I’d never seen it before. It comes from the Hard Rain concert—49 years ago today!—and centers a person you don’t normally see in such shots: The cameraman! I wondered who that was shouldering that video camera a couple feet away from Bob’s face, capturing the Hard Rain close-up footage you’re probably familiar with.

His name is Paul Goldsmith, and it turns out he shot some of the Rolling Thunder footage used in Renaldo and Clara too. At the time, he was part of a guerilla video collective called TVTV that used gonzo journalism techniques for TV documentaries. (Goldsmith made a documentary about TVTV a few years ago; it’s where Bill Murray got his start, a few years before Saturday Night Live.)

That led him to Dylan’s Rolling Thunder orbit, first as an independent cameraperson who joined partway through the 1975 tour, and then bringing his full TVTV team to shoot Hard Rain for a promised NBC special. That shoot came on short notice, after Bob nixed an earlier tour film shot by Burt Sugarman’s Midnight Special crew a few weeks prior. Goldsmith was reluctant to share too many personal stories, but he told me about the work itself, and how his camera captured Hard Rain. This interview has been edited and condensed.

How did you get on board the tour?

I had known Howard Alk. Howard was Bob’s filmmaker partner and close friend. Bobby Neuwirth was his partner in the music world; Howard was his partner like that in the film stuff. I had done a couple of films with Howard. He did a film on Janis Joplin that I did some work on, so he was the one who suggested me to Bob.

Actually, I did turn it down initially when they started the tour. But then they called again a couple of weeks later and asked me to come. So I did.

Why did you say no at first?

Well, I was part of this video collective called TVTV. There were five or six partners, and the partners all committed to just doing TVTV projects. If we left to work on other projects, it would be hard on the company. So that’s why I initially said no. Basically, I had things to shoot.

What changed your mind a couple of weeks into the tour?

I don’t know. Sometimes when you’re asked a second time…

I must have gone to the group and said, “Look, I really want to do this. Just let me go for a couple of weeks.” Whatever I was paid, I might have had to pay into TVTV, I forget. But somehow we came to terms so I could do it. It turned out to be a good thing not just for me, but for TVTV because then we produced the Hard Rain NBC show.

What did a day look like on the road? What was your job?

Well, it was all up to Bob. We were director-cameramen: myself, Dave Myers, and, to a lesser degree, Howard Alk. We filmed a certain number of concerts where we added more cameras in addition to us, and then I think we filmed some concerts without additional cameras. I went to, I don’t know, 19 or 20 concerts, but I didn’t film them all.

And then we were making Renaldo and Clara, where Bob was attempting to make a feature film where he ostensibly was directing. But some of it was just a tour documentary with director-cameramen roaming around filming what seemed to be of interest. Like the piece of Joni Mitchell playing “Coyote” at a party at Gordon Lightfoot’s house, I remember, Larry Johnson, one of the producers, saying, “Come on upstairs.” And that’s when we filmed Joni.

What were you trying to capture with the concert footage? A song like “Isis” is some of the best concert footage of his career.

I agree, “Isis” is wonderful. And I think a lot of it is my camera, because I was up on the stage with him.

When you’re filming a concert, you’re really doing the best you can to be eyes for an audience that isn’t there. So we had cameras positioned on Bob and whoever he was singing with—Bob and Rob [Stoner], or Bob and Joan [Baez], or whatever. You sort of follow the music. You try to capture as much as you can so that the audience of the film can choose what they look at.

It’s less interesting if the camera is just looking at one person, because then the audience is just looking at that one person. If you can put a group of people in the frame and let the audience look at what they want to, that’s the most interesting.

Are you choreographing a concert or a song, planning it out in advance? “At this part there’s the guitar solo, so we need to make sure the camera’s here.”

No. For one thing, that wouldn’t have worked very well with Bob, because every show was different. With Joan, every show was the same—and they were all really good, the audience was with her, but they were identical from day to day. Every show with Bob was different. Every single one.

And in order to do choreography, you’d really need rehearsals, which we didn’t have. So you just sort of felt your way through. I think that’s why people like myself and Dave Myers were hired. That’s what we did. We had the experience and skills to capture visually what was happening in front of us, and enough sense to realize what might be interesting.

I had done a bunch of it before TVTV, I did the movie When We Were Kings, where I went to Zaire with Muhammad Ali. That originally had been a concert film, and in fact was ultimately released as Soul Power, which was the concert film that initially we thought we were filming, along with the fight. So I’d done a bunch of concerts. I’d done stuff for Neil. I had a lot of experience in that.

And there weren’t too many people in those days who did that sort of work, because it was film, and film itself was very expensive. Each camera had 400 feet of film in it, and to shoot that 400 feet, which lasted 11 minutes, cost about $1,000. That was an enormous expense. So you tended to hire the people who knew what they were doing, which then made it kind of a closed loop. The people who knew what they were doing were the ones who had done the last big concert, so they got hired again. There was a limited number of names that would be called up. I was one of them.

Renaldo and Clara must have been an enormously expensive undertaking then, because there’s so much footage from off stage for the movie.

Yes, it was very expensive, but we were never told to conserve film

Before we shift gears into Hard Rain, were there any memorable scenes you filmed yourself for Renaldo and Clara? I don’t know which you shot. Kerouac’s grave, Niagara Falls, Mama Francesca’s…

Well, there were some great scenes that weren’t used in the film, but I think that we should let that sit in Bob’s world. Maybe some of that will emerge.

I mean, a lot of it did, in the Scorsese movie.

I was there at the Lincoln Center at the premiere. Marty came out and said, “You know, this director in the film is a fictional character. That wasn’t the director. It was actually three director-cameramen.” And he called my name out, and Dave Myers and Howard Alk. I thought that was good.

It was an interesting idea, Renaldo and Clara, if it had an idea at all, which was basically a triangle between Bob and Sara and Joan. In my mind, they’re sort of archetypical, the different women. Joan is the woman of very assertive and performance and accomplishment-oriented woman who succeeds in the exterior world. And Sara is a very powerful woman whose success is mostly through men, the person she marries and the family she has and so on. And Bob was the connection between them.

It was some in the movie, but not very well identified. And I don’t think it was really talked about at all in Marty’s film.

Were you there for the Indian Reservation doing the Thanksgiving?

No. I was with Bob for another Thanksgiving. Bob’s mother was there, and Joan Baez’s mother. I just remember there was a long table. A lot of people had gone home, but there were maybe 20 of us there at Thanksgiving. It was just a family event, no cameras. We just ate turkey.

Throughout all of this, both '75 and '76, are you getting much instruction from Bob himself?

Certainly. At first I couldn’t understand what Bob had in mind. Then I realized that talking to Bob in this context is a little like trying to make sense out of jazz. It’s not a melody that you’re familiar with. It’s just touching base on that melody here and there. He would be giving directions of sorts, but they were a little cryptic. But after a while, you got used to what he had in mind.

Do you remember any examples of cryptic directions?

Not really, but I remember one day I was going off to film Joni Mitchell. She’d asked me to film her doing some scene. I mean, this is how informal it was. I was going by with my camera and my soundman, and we passed [Bob] in the hotel. Bob saw me. He said, “Where you going?” I said, “Oh, I’m going to see Joni.” “What for?” “Well, she wants me to film the scene.” And Bob said, “Paul, this is my movie. Come with me.”

So that was about the most direction I’ve ever gotten from Bob.

I mean, you talked to Rob Stoner, right? I’m sure in music, the same thing is true. I’m sure he didn’t give a lot of specific direction to the band, but they got a pretty good idea of what he liked. And I’m sure they got a very good idea of what he didn’t like. And that was music, which was his world. In film, it was vaguer. I think his strategy was just to throw it out there. After all, he had control of all the footage, so he could use what he wanted. He just let us do what we were doing, and later on in editing, he’d do what he wanted.

Some of the band members I’ve interviewed talked about Sam Shepard being there writing scenes on the fly. Did you have much interaction with him?

Well, he was around a lot. I had no idea there was a script. [laughs] It was only going to read his book afterwards that I read that. He may well have been talking to Bob in the background, and certainly he must have talked to Bob beforehand, but I don’t remember any discussion. It wasn’t like a regular movie. I mean, I’ve shot all these movies. They have scripts and call sheets, and you’re going to do these 15 shots. It’s very under control, in so far as that stuff ever can be. This, there wasn’t any attempt at that.

I think it was really a wonderful thing that Bob did. He wanted to put together a sort of traveling circus of talented people. It wasn’t just the musicians. If you think about the writers, it was Sam Shepard, one of the great playwrights of the last half century, and Allen Ginsberg, one of the great poets. Anne Waldman was along, also a poet and someone I’ve grown up with in the Village and known her for a long time. Then he brought these filmmakers in who were artists in their own right. And of course the performers themselves. Normally a tour doesn’t have that kind of divergent talent. You have the star and the musicians. But Bob created this world that wasn’t just Bob. And I think that was extraordinary.

Let’s shift to the second half, Hard Rain. How does TVTV get involved in that?

We did Hard Rain because I had filmed Rolling Thunder for him. So when they wanted to do the concert, they called my company. That was the last performance of the tour [second to last, but close enough], which had gone on for a long, long time. It must have been a decision on Bob’s part at the last minute that he wanted to record it, because I got a call three days before the concert.

Really? Three days?

Yes, it was very last minute, which might have been good. I think one of the things about performance is if the musicians have time to look at the footage and critique it, they’re often not happy with it. There’s something that isn’t quite right, something that you or I might not notice, but something musical that isn’t quite up to their standards, and they want to redo it. But when it’s the [second to] last performance of the tour and everyone’s taking off in different directions, it’s a sort of do-or-die situation.

It was actually a great show, but they were thinking about canceling the performance. It was raining, and there had been a show in Canada a week earlier where a guitarist had been electrocuted and died because of the electricity going to his guitar. So there was concern that this could be dangerous to perform in the rain. And everybody was exhausted and it could easily have been canceled. But it wasn’t.

You’ve probably had the experience in your life in some way or other where you’re not sure whether you want to do something or not, and then when you decide to do it, you just go hell’s bells for it, because you’ve now passed any sort of standards or critique, and you’re just going to fucking do it. I mean, as you can see in Hard Rain, they just rocked and rolled the whole show. I don’t know too much about music, certainly not at the level of any professional, but you could just feel the energy. Everyone on the stage was obviously letting loose. There was no constraint. There was no sense of being careful.

There was an intermission where Allen Ginsberg recited Howl. I wish I’d filmed that, but we were at that moment kind of regrouping, figuring out what we were going to do next. I would have loved to have had a camera shooting that. He came alone on the stage, shouting out Howl to 22,000 college kids in Colorado Springs.

You screened the film for Bob at his house, alongside the Midnight Special version from Florida, so he could pick one to use I guess. How did that happen?

That’s when Bob lived in Point Dume. TVTV was the producer, so we made it, and then the editing was a couple of our partners along with Howard Alk. They had cut a 10-minute piece or something. We screened our 10-minute clip and another clip from the Midnight Special one, the first attempt at this kind of film. And that stuff was just horrible.

The thing about Hard Rain is we shot that on video. Renaldo and Clara and Marty’s film is on film, which has a slightly different, grainy quality to it. It’s beautiful, but it feels kind of framed, like it’s in a picture frame or something. Hard Rain is video. Video has this presence that feels live. So you’re standing right next to Bob and Joan. Up close. You could put your arm around the two of them. That’s where my camera is. Plus, that kind of gray light from the rainy day is perfect for video. It fills everything in and feels just natural.

So what we screened that day at Bob’s house just felt incredibly vibrant and virile and youthful, which Bob was looking for. Because Bob was getting a little older, too. He wanted to be hip and current. And the way we filmed it, that just felt like punk. And the other version is a big stage with this little figure on it, and the cameras are wide, and they have star filters that make the lights kind of twinkle. It could have been John Denver on that stage, because the visual style overcame Bob’s qualities. Which is hard to do, but if you put enough filters on the camera and you film wide, it’s possible. Anyhow, there was no comparison. You couldn’t have had a more extreme example of the new and the old, the moribund and the vital.

It was a fun experience, particularly because [the Midnight Special people] all had so much money, and we were making no money at all. Sugarman showed up in a Rolls Royce and had gold chains. They were clearly on the way out. We were the new wave.

Bob shipped a crate of the [Hard Rain] records to us. At first we were very pleased, and then we played them. About three or four songs in, the needle would skip. We tried another one, and the same thing was true. The needle would skip, again and again. I realized, “Oh, that’s a box of seconds.” But that’s perfect Bob. He’s the best person I’ve ever met at pushing buttons, god bless him.

Thanks Paul! Check out more of his work at PaulGoldsmithASC.com and the TVTV documentary at tvtvfilm.com.

Thanks Ray, Another great interview. This adds a lot to RTR and R&C. The moment at the end when Bob evaluates the 2 film versions, TVTV and Midnight Special, is fascinating. You ask the question as if you knew about this comparison session!

So - when are we ever going to see this stuff in decent quality? They could put out both 75 & 76 as 2 separate releases - would be amazing.