Producer Beau Hill on Chaos and Confusion Making Bob Dylan's 'Hearts of Fire'

"Let's see if Bob can remember his instructions from fifteen seconds ago"

Flagging Down the Double E’s is an email newsletter exploring Bob Dylan performances throughout history. Some installments are free, some are for paid subscribers only. Sign up here:

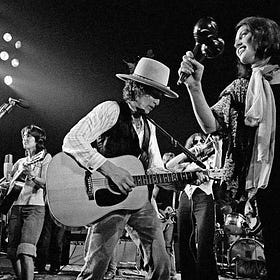

On this date in 1987, Hearts of Fire was released. If you know anything about the movie, you know it practically defines the term “flop.” Though today some defend it as a should-be cult classic, at the time it was greeted by what The Independent described as “almost uniformly vituperative reviews.” It did so poorly at the UK box office that it only received a very limited US release before being sent straight to video (SPIN called it “so bad it didn’t get a chance to bomb”).

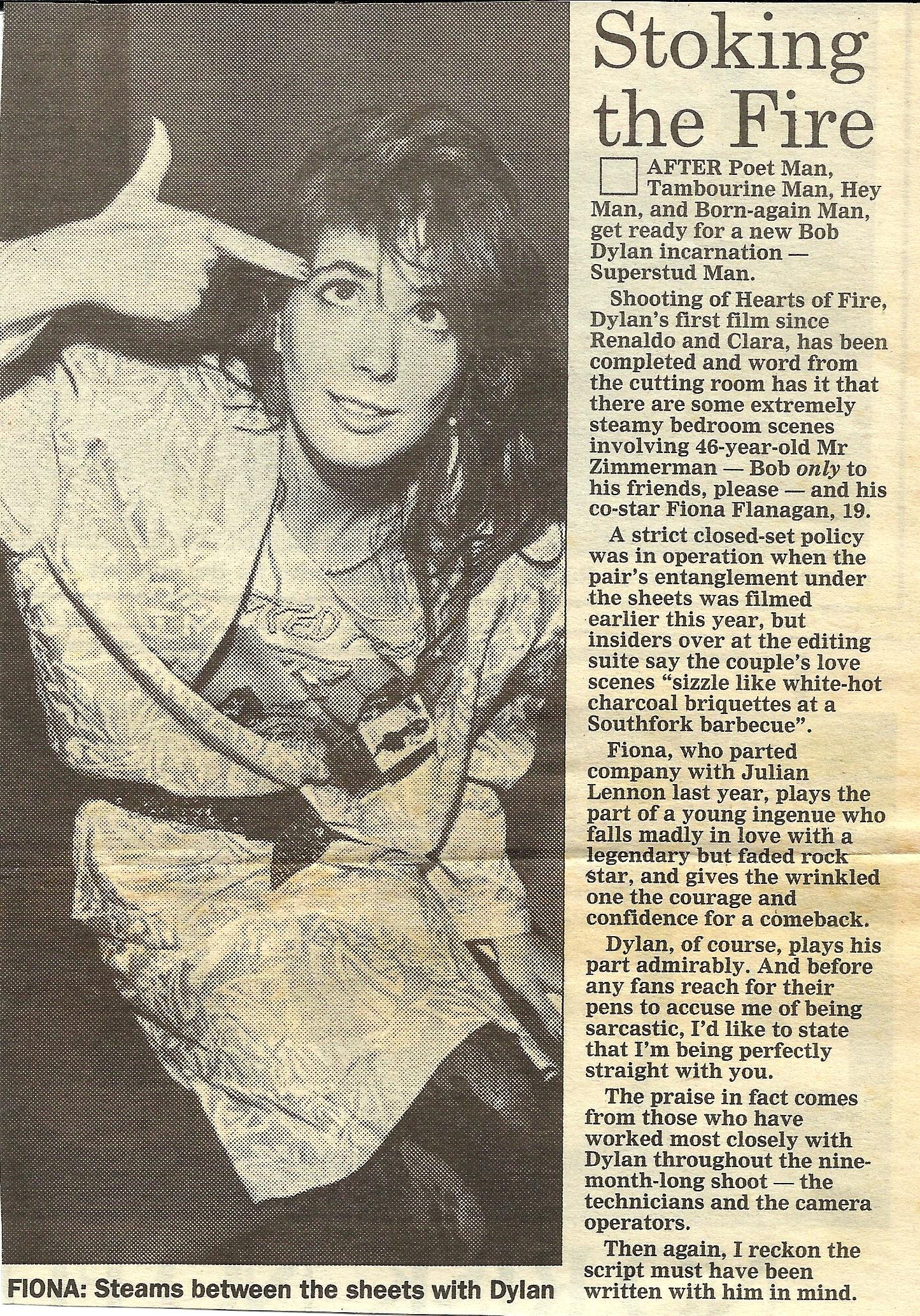

The movie depicted a 1980s twist on A Star Is Born. A reclusive aging rockstar, played by Bob Dylan, stumbles upon a brilliant unknown singer, played by the mononym’d Fiona, singing with a bar band. He reluctantly mentors her to stardom even as a jaded popstar played by Rupert Everett latches on. A love triangle ensues, as does the fakest stage punch ever thrown.

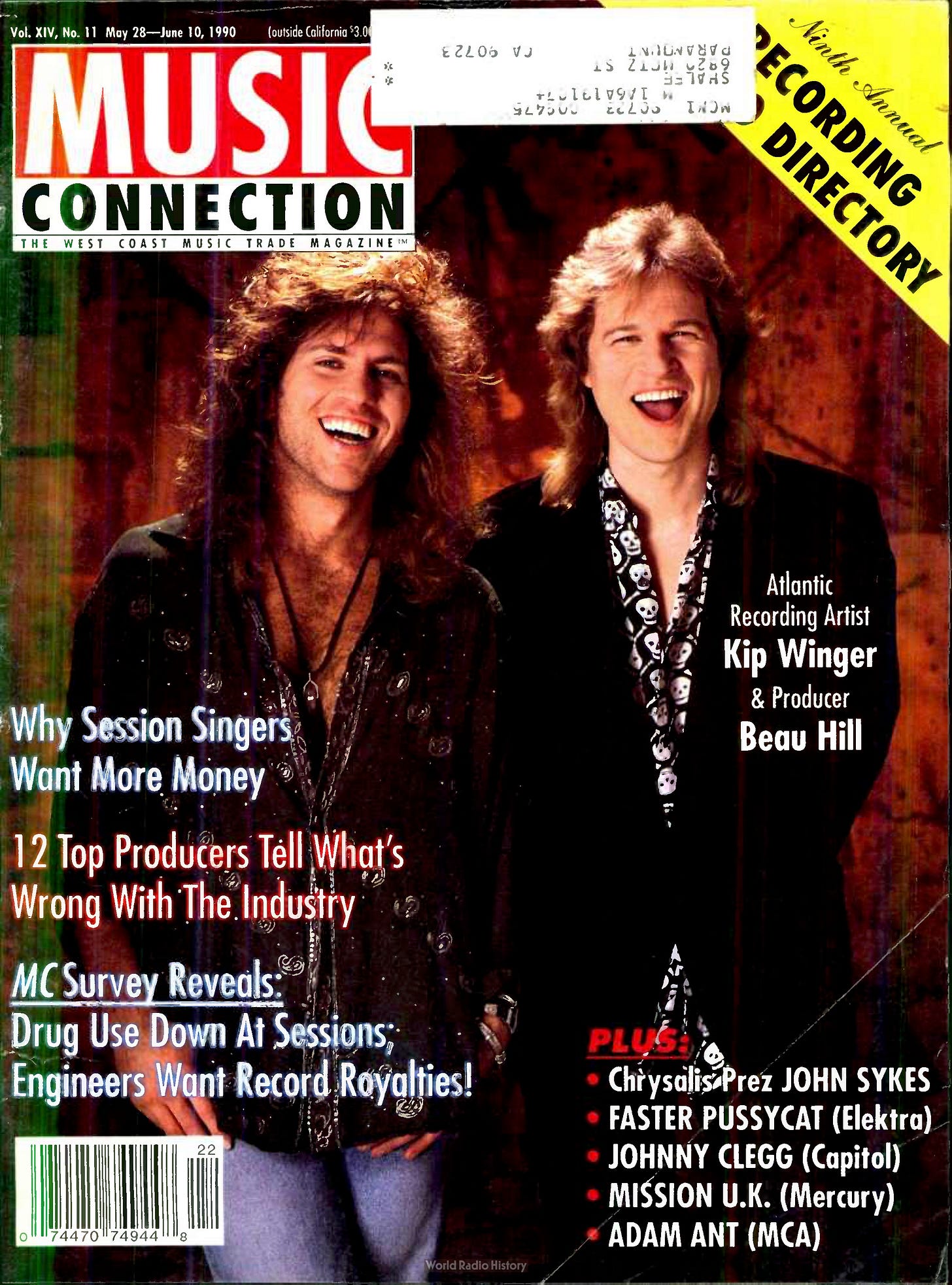

I recently spoke with Beau Hill, who was Music Director on the movie and produced the soundtrack, which features Dylan on three songs: “Had a Dream About You Baby,” “Night After Night,” and the John Hiatt cover “The Usual.” Hill was then best known for his work with '80s hard-rock and glam bands like Ratt, Warrant, and Winger. He recalled his experiences working on the cursed production, which even Dylan himself soon disavowed. “I did it for the money,” Bob told an interviewer in 1992. “I mean, why else would I do it?”

Watch the trailer if you need a quick refresher on the movie, then read my conversation with Beau Hill.

I rewatched the movie last night.

I’m so sorry to hear that.

It’s a wild ride, that’s for sure. Let’s start at the beginning. How did you get involved?

My introduction into this film came from several different angles. The primary one was Fiona. I had written her first single—I hadn’t met her—and then Doug Morris from Atlantic wanted me to produce her record. So I did that. Then she got this part in this film, I don’t remember exactly how. But as soon as she got in, then I was in.

Were you dating already at the time of the movie? Married?

We were dating. We hadn’t gotten married yet.

Somehow Doug Morris became executive producer of the film. I don’t know if that was to close the deal with Fiona or what, because as memory serves the soundtrack came out on CBS, not Atlantic. I wasn’t really sure what that connection was. But anyway, Doug wanted me to do it. Fiona wanted me to do it.

Somewhere along the line, I think somebody made Fiona’s participation—I’m trying to figure out how to say this, that they would let her do the film if I did the music. So I was kind of drug along.

That leads me to a very basic question, which is, what exactly was your job on the movie? Beyond the soundtrack.

It’s called Music Supervisor, a.k.a. whipping boy. The one thing that this movie did for me was it cured me of ever wanting to be Music Supe again.

I’m an independent producer, so I run my own show. I select the material, I select the studio, I select what days we’re going to record, I select what time we’re going to record. It’s pretty much all on me. Not so when you get involved with movies. I had to get fifteen executives to sign off on a ham sandwich. It was very awkward, very cumbersome, and very inefficient.

It’s funny you say that because I had a thought at the very end of the movie. When the credits rolled, it struck me like even for a movie that is a flop by any definition, an insane amount of people worked on it. Hundreds. As opposed to an album where you might have a dozen or less.

[Director] Richard Marquand did the [third] Star Wars movie, and then he did something else with Glenn Close [Jagged Edge]. So he had a very successful pedigree, and I think that’s also what brought people along. They wanted to be in his orbit.

And he landed Bob Dylan, for crying out loud. That was no small feat.

Was Dylan already involved by the time you got brought in?

I was involved very early on, from the first meeting that Fiona had with Dylan out at his house. They set up a small film crew out there, just so everybody could look at it and see if there was the quote-unquote “energy” between those two. So I was involved all the way back then, before she actually even got cast.

So you were at the house for that screen test? What do you remember about that?

It was just cumbersome. Everybody’s falling all over themselves to try to impress Bob, and Bob was beyond impressionable. I mean, look, if you’ve been Bob Dylan for thirty years for crying out loud— He was well beyond all that and well over it.

He was pleasant and cooperative, because this is the first movie that he was starring in, but it was just too much bowing and scraping, let me put it that way. I’m not a real bowing and scraping kinda guy.

So Fiona gets cast, things move along. Once the shooting starts, are you visiting the set?

I missed the first five days because I was finishing Ratt, the Dancing Undercover album. I delivered that record and got on the next plane to London. So I missed the first five days, but I was there for every other painful moment.

I gotta interject because you mentioned Ratt. Had you seen that clip I sent you where Dylan asks some kids about Ratt?

I had never seen that clip before you sent it to me. When I looked at it, I was like, “Damn, where’d that come from?”

That was done in Toronto on the set. We did a bunch of principal photography in Toronto, as well as the big concert sequence. I think it’s supposed to be in England, but it was actually done in Toronto.

Do you think Dylan knew about Ratt from you?

I have no idea. He never talked to me about it. But he probably asked somebody, “Who’s this Beau guy and what’s his story?” And they said, “Oh, he was the guy that broke Ratt.”

I’m sure it was something innocent like that. I have a feeling he was just screwing around with that kid in the parking lot. Bob certainly was not interested in my projects, least of all Ratt.

So Dylan was maybe not a huge Ratt fan. How about you? Were you a big Dylan fan?

He was more what I would characterize as folk-rock, and I was not so much into folk-rock growing up. I mean, listen, a few of Bob’s most memorable hits I thought were great. Now, was I a diehard Dylan fan? Did I play him constantly? No, I did not.

Do you remember your first interaction?

At his house. That’s when I met him the first time. I didn’t have any sort of introduction other than I was there with Fiona. As far as he was concerned, I was probably just the annoying boyfriend. I was pretty quiet and in the background, because Fiona hadn’t gotten the gig yet. So I wasn’t about to stick my big nose in the middle of where it didn’t need to be.

So you missed the first five days of shooting. What do you remember from day six on?

Bob had told everybody involved that he doesn’t want me near his music at all. He didn’t know who I was. He didn’t care. He was going to take care of his own music. So when principal photography began, the understanding from Lorimar [the production company] as well as Richard Marquand and Atlantic and everybody was Bob is bringing his own music. He will be ready to film to his music on day one.

Well, day one never happened.

Oh God, I just remembered this. I was responsible for Christophe Lambert. You remember the guy that played Tarzan? He wanted to have Rupert’s gig. I remember I was in LA in the middle of Ratt. I got a call from the production office. “Listen, we need a big favor. We need you to take Christophe into the studio and do a couple of demos with him and see if he can do this.” So we went into the studio. To call it a disaster would be unfair to disasters.

What happened?

He didn’t have a band, he didn’t have any music, he didn’t know anything. If memory serves, I got him to try to sing along—it wasn’t even karaoke, ‘cause there was a vocal on whatever this song was. I think it was “Tainted Love,” because we actually wound up doing that one with Rupert.

He struggled with that, let me put it that way. This was right in the middle of me doing Ratt. So I had to sneak off a day and go do this thing with Christophe and then report back to the Lorimar office that, no, this guy can’t carry a tune in a bucket.

That was pre-principal photography. So I guess I was involved early on, because once Fiona got the gig, I was responsible for her music. Then somehow I got sidetracked into this Christophe piece of it, and then that just naturally dovetailed into me taking care of all the Rupert material as well. My job was, I was supposed to take care of Fiona and Rupert Everett’s material.

So I get to London, I’m ready to go. One of the assistant directors came to my room and said, “Mr. Marquand would like to have a word with you.” [Marquand] said, “Beau, I have a problem, and I need you to help me with this.” I went, “Certainly, what can I do?” He said, “Go down to Townhouse Studios and get Dylan sorted out.” I’m like, “What does that mean?”

He said, “All we know is that Dylan was supposed to show up with his music for all of the concert sequences—and Dylan doesn’t have any music. But he’s at Townhouse Studios right now recording some stuff. I need you to go down, listen to what he’s got. I just need to figure out where we’re at, because I’ve got all these concerts scheduled.”

I mean, we were in production at that point. So it was pretty serious. So I said, “I’ll go down straight away.” And I did.

Now remember, I broke my career with Ratt. I had just finished their second album, and I had finished the first Warrant album, which was also a hit. So I was still pretty young and inexperienced.

I walk into Townhouse. The person in the front says, “Are you here with Hearts of Fire?” “Yes, I am.” “Okay, follow me.”

They had three or four studios at that time. So I’m walking down the hall, and the first thing that I see is, I turn to the right, and Queen is recording. The door was wide open and there they were. I was just like, “Whoa!”

So I continue on down the hall, walk into my studio. There was a very flummoxed—what they call them over there is “tea boys.” They’re the guys that get coffee and tea. They’re like the second assistant engineer. Pretty far down the totem pole, as far as the British studio hierarchy goes. This kid is sitting in there behind the console, running the session.

I stick my head in, and here’s what I see. I see Bob Dylan with his guitar, Eric Clapton with his guitar, Ron Wood from the Stones playing bass, and Eric Clapton’s drummer Henry Spinetti all, in the same room. They’re just jamming. That pretty much took my breath away right there. No one told me that Clapton was there. And Ron Wood.

What had happened is, I guess, Bob came to England, picked up the phone and said, “Hey, can you guys meet me down at the studio? I need to come up with a couple of quick songs.” Of course, everybody dropped whatever they were doing and they went to help their old friend Bob Dylan.

So I walked in, and there were literally 20, 25 rolls of two-inch that had already been recorded lying on the floor of the control room. And this poor kid, I mean, he just looked up at me, and it was like, “Please shoot me.” Because he didn’t know what to do. He wasn’t keeping any notes because there were no notes to keep. “What do I have to work with?” “I don’t know.”

Just a bunch of amorphous tapes of jamming?

Of jam tapes, yeah.

So I went in and said, “Okay, let’s call it for today, because I’ve got to have some time to go through all this and see what we got.”

The little dark backstory is that Eric and Spinetti were sober as a judge. He had now crossed over and he was in his clean sobriety, non-rock-and-roll-crazy. And Dylan and Ron Wood were the opposite. So half the session was like completely, totally one-hundred-percent pro, and the other half was…not. Let me put it that way.

There’s a scene from the same documentary that the Ratt thing comes from. Right at the beginning. They’re like, “All right, Dylan, let’s do this interview.” He goes, “I’ll be back in a second.” He abruptly leaves, and when he comes back, he’s sniffling a lot.

There was a certain amount of that.

So long story short, I spend a day listening to all this. The tea boy said, “All they did is they told me to keep putting fresh reels of tape on. Just hit record and let it go.”

So it was everything. It was those guys sitting around talking, telling jokes, just screwing around. “Hey, let’s try twelve-bar blues. Key of D. One, two, three, go.” Stuff like that. I mean, it was 25 reels of stream of consciousness.

How many hours would 25 reels be, ballpark?

Well, at thirty inches per second, that was probably 20 hours.

Dear Lord.

But it wasn’t them playing all the time. It was just however long they were in there, they kept tape rolling. Then when the tape ran out, [he] pulled that reel off, put another one on, hit record, sat back down, and twiddled his thumbs. Poor guy.

So how do you make sense of all this?

I listened to it, and then I went, “Okay, now I understand what this is.” And it was nothing. We had a huge studio bill and nothing whatsoever to show for it.

So I went back to Richard and I said, “Okay, boss, here’s the deal: You don’t have anything.”

I’m sure he was thrilled.

He had some sort of uncomfortable conversation with Bob. He basically said, “Bob, look, all the stuff that you’ve been recording, we can’t use it. We need to have a couple of real, live songs.”

Now I wasn’t part of this conversation, but my understanding is that Dylan was miffed. He wasn’t angry, but he was miffed and he had to make some compromises. His idea of a compromise was, “If you don’t like any of the stuff that I’ve come up with, there’s only one person that I will record their material: John Hiatt.”

The next thing I know, Richard said, “I need you to go to Nashville and have a meeting with John Hiatt and pry a couple of songs out of him for Dylan to do.”

So I got on a plane, flew to Nashville, went to a club John Hiatt was playing that night. Tremendously nice guy and very accommodating. I got him to sign off and give me some material. I brought that back. I played it for Bob. Bob said, “Okay, I’ll do it.”

Then we had a blueprint. I probably charted out an arrangement real quick because the song is a pretty simple song. Then Eric and everybody played it.

It was a very surreal experience for me because I grew up with Eric Clapton from when he was playing in the Yardbirds. I was sitting in there and we’re doing overdubs or something, then all of a sudden, this guy that I’d looked up to for all these years turns around to me and says, “What do you think, Beau? Was that okay, or do you want me to do it again?” I was just like, “Man, you can’t make this shit up.” He was the nicest, most professional person, especially considering his pedigree and the fact that he was talking to a mutt like me. I mean, he treated me like I was George Martin.

And how did Dylan treat you? Given he initially didn’t want some outside producer he didn’t know.

My impression was that he just wanted to get this over with. “Is that good enough?” “Uh, well, have you got another one in you?” “Nah, I think that’s pretty good.” “Okay.” That’s how that went.

I have a feeling that the air went out of the balloon for Dylan pretty early on. And that he was kind of like, “Why in the hell did I sign up to do this? We’re not having fun anymore.” Down to the point when we were doing all of the concert sequences, Dylan couldn’t remember the words. So Richard said, “Beau, can you go stand in front of Dylan?” I was like an orchestra conductor. I was standing there counting him in, saying, “Okay, get ready to sing ‘The Usual.’ Ready? One, two, three, go.” I’m flapping my arms like a chicken and mouthing the words to him.

It was quite something, but it was also an emergency, because we had run out of time. We had to get this principal photography done, come hell or high water.

Do you remember anything about recording the two Dylan originals, “Night After Night” and “Had a Dream About You Baby”?

Not really. I do remember when the movie was finished, I took all the tapes back to New York. Once I was there, and I was back in my element so that I could function like I normally functioned, then I was able to go in and clean stuff up. For example, I think I completely redid Ron Wood’s bass part because it was not usable.

I kept all of Clapton’s stuff, I kept all of Henry’s stuff and I kept whatever of Dylan’s that I could. Obviously his voice. But then I was given pretty much free rein to do whatever needs to be done to get it where people will listen to it. Because at that point, no one cared. It was just here, “Beau, be the musical janitor and clean up this mess. Then give it back to us so that we can release it with the film.”

Does that include overdubbing? Because Kip Winger is on the record, Reb Beach is on the record. I gather they weren’t at the sessions in London.

I just pieced it together well enough where we had some music for Bob Dylan to pretend that he was performing at all of those at the live sequences. Once that was done and we had the tempo locked in, then I took it and tried to make a decent record out of it. So that’s where Kip came in and that’s where Reb came in. I got a chance to get some work for my for all my friends that were broke, trying to hopefully get on board with something that might help their careers out.

So what else were you doing on set? You mentioned that funny story of standing in front of Bob during the concert scenes. Did you have any other role on the filming side?

On the filming side, I was there to as a backstop for anything going on musically. When they would go and film studio sequences, I was there for all of that stuff. More as an advisor. Richard was asking me, “Is this how it’s really done?” “Does this look right to you?”

There are some extensive studio sequences with Fiona when her character is recording her debut.

Fiona’s trailer was right next door to Bob’s. So I talked to Bob every day for three months.

Any memorable conversations from all those stick out?

We had a couple of interesting conversations when we were standing around the trailer getting ready to go to work, but they were very light, nothing substantive at all. He was pretty quiet, at least around me. He was being bombarded with instruction and direction and wardrobe and all that kind of stuff. People were fussing over him all the time.

We had some interaction when we were in Toronto. If memory serves, I think I had to go to the studio with him in his car. He and I were having a little coaching session on what we were going to try to accomplish at the studio that day. But there wasn’t really a whole lot.

I mean, from my remembrances, Bob was not necessarily the warmest, most outgoing person. But he wasn’t rude. He was just kind of quiet and stayed to himself. It was like, why in the hell did he need to talk to a moron like me anyway?

Bob had some friends that would come over and hang out with him. He had a constant stream of fans and admirers and things of that nature. So that’s another reason why we didn’t talk to him too much. He was busy hanging out and entertaining his guests.

I read some report from the time that he was juggling girlfriends, trying to coordinate their visits to not overlap.

I wasn’t sure if that was speaking out of school or not. On set, we called it Mrs. Bob of the Week. “Who’s Mrs. Bob of the Week?”

There are a lot of other musicians in this movie. Richie Havens. Ian Dury from the Blockheads. And then craziest of all to me was the backing band. Mark Rylance on bass, who went on to win an Oscar, but I don’t think he even has a line, and the sax dude from The Lost Boys, that enormous muscled drummer who’s got his shirt off the whole time.

We had to put together the backup band for the live sequences. Richard came to me and said, “Can you help?” So we sent a bunch of plane tickets to New York, sent everybody up to Toronto and said “Pack your bag, you’re going to be up here for a couple of days.”

The Lost Boys dude, I’m not even sure he has a line, but probably just ‘cause he looks so dramatic, he gets a ton of screen time in the movie. And he never has a shirt on. It’s a funny person to ostensibly be backing up Bob Dylan.

Yes. The incongruities just continue to grow in this film.

So the movie comes out. It is, to put it mildly, not a smash hit. What were your thoughts on the movie, thoughts on its reception?

I thought it was terrible. I thought it was embarrassing. But my big takeaway from the debut was I got to meet two of the Beatles.

That almost makes it all worth it.

Almost.

Which two?

Ringo and Paul. They showed up to support their pal, Bob Dylan.

As I said, I’m very glad that I did it, if for nothing else, to know that I never wanted to do that again. Ever.

Did you ever talk to Dylan after the premiere?

We had one chance encounter, and this is really weird.

The movie was finished, the premiere had happened. Back in those days, everybody was flying on the Concord. So we showed up at the airport and, lo and behold, there was Bob.

Bob was acting like he didn’t know who we were. It was the strangest thing ever. I just walked right up and said, “Hey, Bob, how’s it going?” He started looking around over his shoulder like he didn’t want to acknowledge me or something. Then he did the same thing to Fiona. “Oh, yeah, uh, oh, yeah, I’m doing fine. See you later.”

It was just one of those uncomfortable things. You know, he’s kind of looking around to see who’s watching us. Nobody was. Nobody cared. He was just another guy getting ready to get on a plane.

I guess for how weird the whole filming experience was, this fit right in. That was the last time that I talked to him.

You were together with Fiona at the time. Did she have a good experience on the movie? Did she feel bad about how it was received?

That’s a great question. I don’t think I ever really even asked her what she felt about it. Because it was kind of universally downmarket.

I mean, when Bob showed up and didn’t have his music—and Richard had an acting coach on set. It was Glenn Close’s acting coach. So this guy knew what he was doing. We were watching him trying to coach Bob and trying to get him into his character, whatever that was.

Bob as I mentioned, musically, he just wanted it to be over, and I think the acting part of it really pushed him over the edge. It was almost like, “I’m going to go through the motions. Whatever you guys tell me to do. If you like it, great. If you don’t like it, so sorry.”

That attitude blanketed the whole experience. Everybody started out with really high hopes, and it was going to be big, and blah, blah, blah. Then it dissipated pretty rapidly when Bob didn’t show up with any of his music.

It sounds like you were not entirely surprised at the outcome of all this.

Oh no. Because I sat there and I was watching his acting coach do the same thing that I did with the music, where he’s like two inches away from Bob, feeding him lines and telling him, “Okay, be sure and smile here” and that kind of stuff. Then it was like, “Okay, let’s take it and see if Bob can remember his instructions from fifteen seconds ago.”

And could he?

Sometimes he did, and sometimes he didn’t. [laughs]

They couldn’t really sugarcoat it to the cast and crew. Pretty soon everybody’s just going, “Oh my God.”

Then in the middle of all of this, Richard got a real serious circulation and pain issue in one of his legs. So on top of everything else, Richard was barely ambulatory. He went to crutches, and then I think towards the end, he was being pushed around in a wheelchair. It got so painful for him. He wound up passing away like two weeks after principal photography was done.

He didn’t even see the thing come out.

His wife showed up to the premiere. She was quite lovely and very stoic and really kept it together. But it was all just a horrible mess there at the end.

I was surprised to learn that John Barry, the James Bond guy, scored the movie. Did you meet him?

I did not. Again, that was the Richard effect. As you watch the film, you’ll remember Rupert’s big dramatic moment.

Which one? Rupert has a lot of dramatic moments. A lot of searing looks.

Well, there was one moment where the John Barry score just jumped in all of a sudden. It was only there for a very short period of time in the entire film. Normally, if you’re going to have soundtrack stuff like that, they have little moments throughout the movie. I think there was only one scene that John Barry wrote the score for.

It struck me as very out of place. It was a beautiful piece, and Rupert was really putting on all of his proper English training in the acting, and then it went away and never returned. When I listened to it, it was like, this makes no sense whatsoever. To have this beautiful orchestral moment in the middle of all of this other silliness.

You’re credited on Dylan’s follow-up album, Down in the Groove, on keyboards. I’m assuming that’s because he included “Had a Dream About You, Baby” on that album?

For records like that, if there’s a part that needs to be played, or a part that needs to be replaced, if I could play it, I just played it.

Early in the morning, I would come in to review what happened the day before and to set my sights on what I wanted to accomplish today. If something jumped out at me and it was like, you need to fix this keyboard part, then I would just fix it. There was no fuss about it.

On one of the Ratt records, they went completely crazy because Warren [DeMartini] had bashed one chord a little bit out of tune. He hit it a little hard. It was bugging me. Since I was in the studio and I had all of his stuff set up, I went in and I replaced the part. The band went nuts. It was like, “You dared to replace Warren’s part?” I said, “Well, yeah, I did. It was out of tune.”

So it’s very possible that I wound up with a keyboard credit on that song, even though I don’t remember it.

Thanks to Beau Hill for taking the time to talk! Keep tabs on his current work at beauhillproductions.com. Bonus thanks to Rebecca Slaman for some question suggestions. The full movie is available to watch on YouTube, as is the soundtrack (I don’t think it’s streaming).

More interviews about Dylan in the Movies:

Ronee Blakley Talks Rolling Thunder, Joni Mitchell, and Performing at a Prison

In fall of 1975, Blakley was riding high on her success in Robert Altman’s movie Nashville, which had just been released a few months prior (she’d be nominated for an Academy Award shortly after Rolling Thunder ended). So she posed a double threat to the tour: Not only a singer who’d already released a couple albums, but the only professional actress of the bunch

Director Michael Borofsky Talks Filming Bob Dylan in the '90s

For much of the 1990s, Michael Borofsky was Bob Dylan’s go-to director. He filmed Dylan on stage: the famous Supper Club shows, a bunch of the Never Ending Tour, advising on MTV Unplugged and Woodstock ‘94. He filmed music videos: the Time Out of Mind duo of “Not Dark Yet” and a never-seen “Love Sick.”

Gillian Armstrong Talks Directing Bob Dylan and Tom Petty's 1986 Concert Film 'Hard to Handle'

When we spoke last month, the topic of conversation was a relative footnote on her resume: Bob Dylan’s 1986 concert film Hard to Handle backed by Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers. Dylan told interviewers he had selected Armstrong personally to direct it, even though, as she is the first to admit, she had zero experience directing concert movies.

One of Rupert Everett's books has a chapter detailing his experience with HoF and Dylan. Interesting read perhaps showing Dylan, at that time, more in another world than otherworldly!

Does he have those tapes? Tulsa? Bootleg Series 38?