Matisse and Corset Ads on Bob Dylan's Mid-80s Album Art

The Empire Burlesque Interviews #6: Nick Egan

Flagging Down the Double E’s is an email newsletter exploring Bob Dylan concerts throughout history. Some installments are free, some are for paid subscribers only. Sign up here:

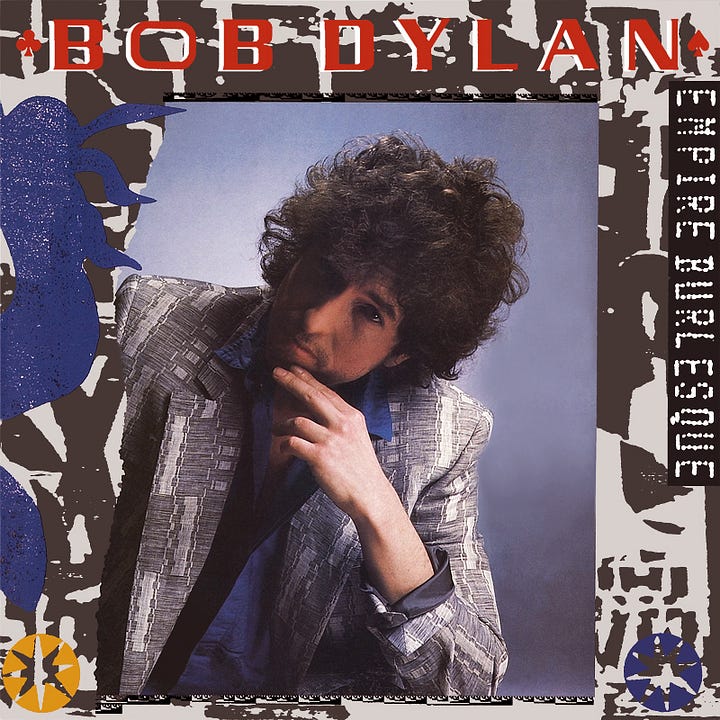

Our weeklong Empire Burlesque 40th anniversary series concludes with one final interview. Taking us home is Nick Egan, the designer of the album cover, as well as of the Biograph box set and Dylan’s original Drawn Blank art book. Egan came out of the British punk and new-wave scenes of '70s and '80s, designing iconic album and single covers for artists like INXS, Duran Duran, and The Clash (his cover for The Psychedelic Furs’ Midnight to Midnight is a personal favorite).

Below, he tells me about how he got the gig after Sex Pistols svengali Malcolm McLaren turned it down, his close working relationship with Dylan in the '80s, and why the photo on the Empire Burlesque cover is not his fault.

How did you get the assignment?

I did work for a long time with a guy called Malcolm McLaren, who used to manage Sex Pistols. He did his own record called Duck Rock which I worked with him on. One day he said, “Bob Dylan is trying to get ahold of me. He wants me to do a video. I don’t know if I’m going to do it. Why don’t you go check it out for me and see what you think?”

I knew that it wasn’t going to be Malcolm’s thing, but I had to give credit to Bob, because nobody knew who Malcolm was. Bob did. That’s the thing about Bob, he was very clued in.

So I went to meet him and [manager] Jeff Rosen at the Hit Factory, I think, to tell them Malcolm couldn’t do the video. They seemed a bit bummed. I said, “But if you have an album cover that needs doing, I’m happy to do it for you.” It was like a consolation prize, right? And they said yes. “It’s called Empire Burlesque, and there’s a Ken Regan photograph you have to use.” I didn’t really like using other [photos]. I wanted to art direct, chose the photographer. But I thought, “It’s Bob. I’ll do that.”

Anyway, I’m in my apartment in New York, and the phone rings at 3 o’clock in the morning. My girlfriend goes, “It’s Bob Dylan on the phone for you.” I’m like, “Yeah, right.” She hands me the phone, and there’s this cracking voice. He’s like, “Hey, it’s Bob. I’m in Russia, man. I’m at a poetry reading festival. There’s 200,000 people here just for words. Can you believe that? Words!” He was telling me a thing that creeps me out. This is in Communist Russia. Several times throughout the night, the door [to his hotel room] opened. Somebody looked in the room, and closed the door.

Then he started to get on to me about, he’s thinking of moving back to the East Village and all this kind of stuff. I was, at this point, really tired and nearly falling asleep. But I thought, what a strange way to start a relationship. I didn’t expect him to call. He went on about this very personal stuff.

Forty years ago, I was 25 or something. I was young. I mean, I knew who Bob Dylan was, obviously. I can’t say I was a fan. So when I met him, I wasn’t that guy that was really impressed by him. And I’ve seen people around him. I’ve seen the way people are very sycophantic. Even people quite high up in the record label. I can imagine he gets tired of that all the time. I think what he liked about me, I wasn’t going to be one of those people. I was this guy from London. I worked with Malcolm McLaren. I was different.

So I went off to work on this cover. To be honest, I wasn’t blown away by the photograph. I know Ken Regan is a very well-respected photographer, but it wasn’t an album cover photograph for me. It was more like a publicity photograph. But they were really keen on using it. So I thought, “Okay, how can I make this interesting?”

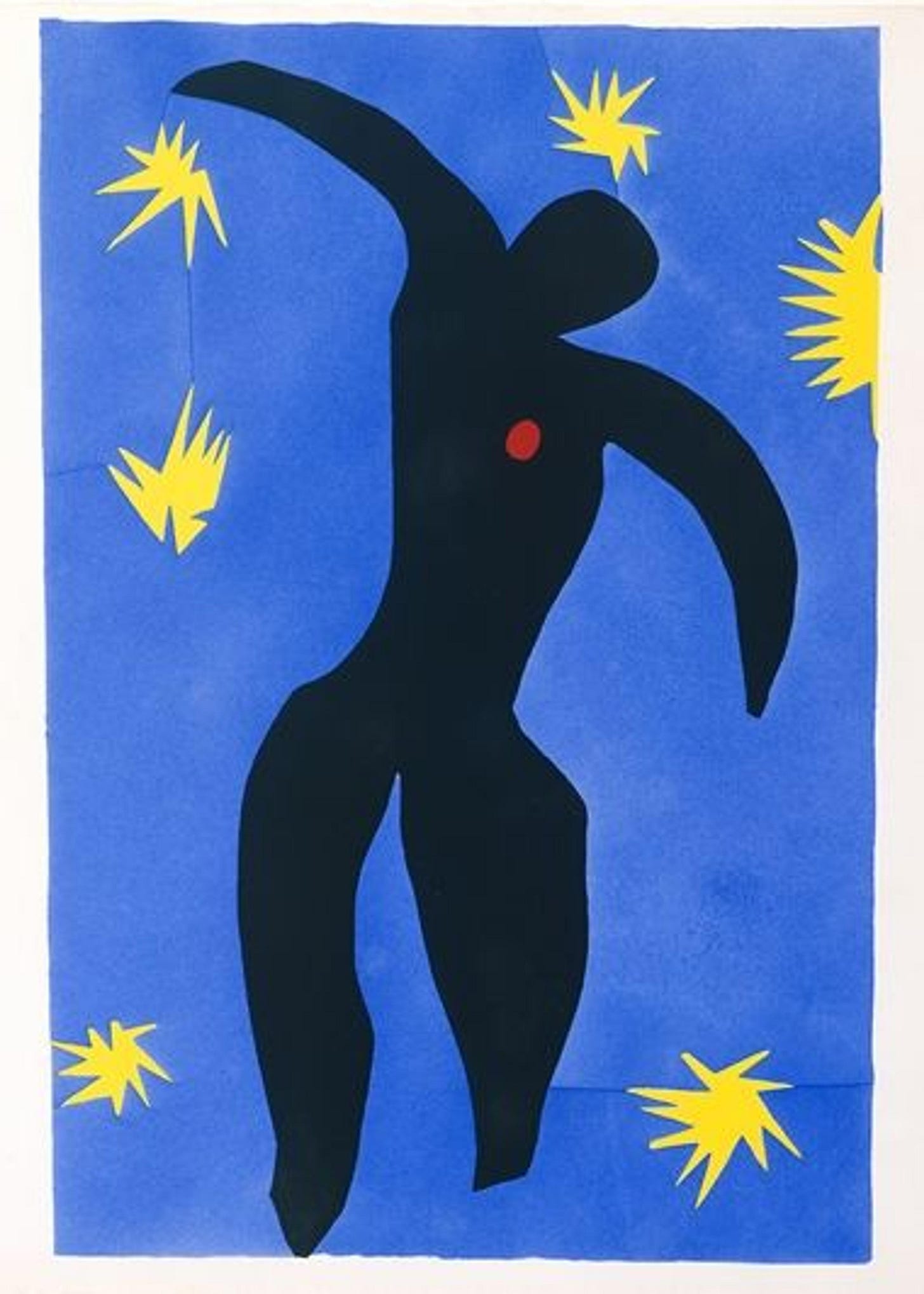

There was a Matisse show in New York called Jazz. And I loved all those silhouettes and those stars. So I took the Matisse star.

And then there was a book that was like classified ads from the 19th century to today. It was all those funny old ads, like some potion that would make your hair grow back. From that book I used the burlesque lady on the back, right next to Bob. I think it was an ad for corsets. In fact all of the grey and light grey background were type from the ads blown up 500%. It was all public domain, because it was God knows how many years ago.

I get a call from [Dylan’s manager] saying, “Have you got the artwork? Bob wants to speak to you. He’s in the Hit Factory.” “Great, I’ll make my way up.”

I’m strolling along. I’m not in a hurry, because these people are in the recording studio, and I think they’re going to be in there for hours. So I’m just taking my time. I popped into a museum.

I finally go into the Hit Factory and I go to the receptionist. “I’m here to see Bob.” She goes, “Oh my god, oh my god, they’re waiting for you upstairs!” I’m like, “Who’s waiting for me?”

So I go up to this room and I open the studio door. There’s a room full of about 20 people. They’re all sitting on the floor around the edges of the mixing room. Bob’s sitting in front of the mixing desk. He’s got an arm around these two Black girls. He looks back to me and says, “Hi Nick, take a seat.”

I look around, and the only empty seat that was in the room was next to the producer. I realized Bob had made that seat my seat. He wanted me to sit there.

So I sit in the chair next to the producer. He didn’t tell anybody in the room who I was. I’m a 25-year-old punky kid, and everybody’s staring at me. I can feel their eyes going into the back of my head wondering who the fuck I am. They’ve been waiting for me to get there, God knows how long, to do a playback. That’s what they were all there for.

So he plays the music to all these journalists and everything. It was all big shots, like Jann Wenner from Rolling Stone. Between every single song, he turned and looked at me. I’m like, “Fuck, what am I supposed to say?” I was in panic mode, because I was going up there to meet with him about the cover, and suddenly I’m put in the spotlight. I was just giving him the thumbs up.

Finally, it stopped. He goes, “What did you think, Nick?” Or I don’t even know if he said my name. He was very keen not to let people know who I was. It was some comment directed to me. I said, “At a first listen, it sounds great. And the words are great.” I realized that was a bit of an understatement, considering he was the poet of the '60s. Really, I didn’t hear the record. I was too nervous at this point.

So everyone got up and walked out of this room. Still to this day, they have no idea who I was.

Bob comes up to me and he goes, “I’m sorry I put you through that, man. But some of these people are assholes. They think they know better, and I wanted to let them know they don’t mean anything. This guy means something.”

I got it. I felt a little bit like, I wish I’d known what I was getting into. But I got the fact that he didn’t introduce me to anyone, because he didn’t want them to know who I was, on purpose. That summed Bob Dylan up to me perfectly.

When people ask me about Bob Dylan, I say he’s really hard to explain. He’s not like anyone I’ve ever met in my life. He’s almost like an idiot savant. He doesn’t like making eye contact with people. He mumbles a lot. I thought Timothée Chalamet nailed that in the film. I just thought, “Oh my God, that is what Bob was like!” He mumbles, you can’t hear what he’s saying, one minute he’s really focused on one thing that’s really important to him, next minute he doesn’t care. It was a very, very strange thing. He’s very up and down. He could be moody and just kind of pissy. You just don’t know what you’re going to get. I wouldn’t see or hear from him for ages, and then suddenly I’d hear and there’s a lot of stuff to do.

So I did Empire Burlesque, and I remember being up at CBS when I was presenting the artwork. I realize nobody up here has met Bob. He was one of the label’s biggest artists, and I don’t think anyone ever met him. People would come up to me and go, “So you met Bob? What’s he like?” And this is like the Vice President of Marketing or something. I think he enjoys that, blowing in and out. He won’t give people the time of day if he can’t be bothered with them.

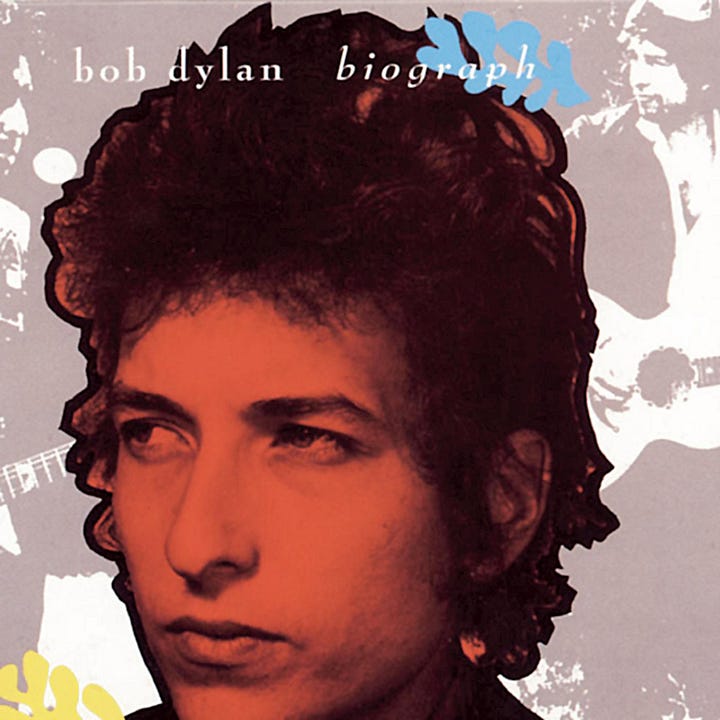

After Empire Burlesque comes out, I get a call from Jeff Rosen. He says, “Bob wants you to do the Biograph album. But you have to come up to Davasee Enterprises”—which was his publishers, up on Irving Place—“and go through the photographs up there. You can’t take them out of the office. And I’ll warn you, there’s 2,000 photographs.”

So I go into this conference room and there’s boxes of photographs and stuff from every country, from every decade.

I’m thinking to myself, “Oh my god.” I remember going through it, and I saw that picture. I probably only got through about 10% of them, luckily. I hadn’t been there for long. As soon as I saw that photograph, I thought, that’s the one. That is the definitive Bob Dylan photograph. Not only because it’s him, but also he looks like Johnny Thunders or John Cooper Clarke. Once I saw that image, I said, “This is Bob Dylan, the king of punk.” Because that is his attitude. He doesn’t give a fucking shit about certain things.

It dawned on me because I didn’t know a lot of his history. I didn’t know about the Newport [Folk] Festival. I didn’t know that caused such a controversy. But I was reading some stuff, and it was so punk rock. He didn’t give a shit. It was like, “I’m not going to be told what I’m going to be.” I thought, “How fantastic.” That’s why I think he related to Malcolm McLaren. They’re very similar. Both Jewish creative people, got this kind of mad creativity to them. I think Bob saw that in Malcolm. Unfortunately, Malcolm didn’t see it in Bob, because Malcolm thought Bob was an old fart.

When I pitched the Biograph [design] to Bob, we’re sitting at Davasee, in the conference room, and I sketched out this little thing, like a thumbnail of a head. And I remember saying to Bob, it’s going to be this, it’s going to be that, and I knew he was getting it. He got the references. He got it from my little sketch on a piece of paper, which I think is magical. When you take a pencil and you draw a stickman on it, it opens up someone’s imagination. And I think Bob, because he’s an artist, and he draws and paints himself, he completely got that.

Gilbert and George were these two British artists that did those photographs where they put primary colors on. That’s where I got the idea, to keep it contemporary and to keep him punk. Because I just thought the picture by itself wasn’t enough. It needed something. What Gilbert and George did, there was always kind of like religious iconography around it. And very gay, like rent boys of London. And that’s what Bob is like. He’s kind of got this religious thing to him.

I remember they had a big party for Biograph at the Whitney Museum, They had all the artwork blown up as you walked into the Whitney. There were all these people there, and I could tell he was awkward. He said to me, “Why don’t you come and sit with me?” We went into some sort of secretary’s office in the Whitney Museum. We were talking, hanging out a little bit, just me and Bob. They were people outside, celebrities, and Bob had no interest in going out and seeing them. That’s what I loved about him, that personality.

I’ll tell you one more story that really does show who he was. This is when we were working on Drawn Blank. It was a project that took forever. He came to my house, right? At the time, I had this little dog. It was this little Lhasa Apso. It was running around, and I could see Bob just following it with his eyes, looking backwards and forwards. I’m trying to talk to him, and he’s not listening to me. He’s looking at this dog.

He looks up to me and he goes, “My daughter would love this dog.” “Well, if you come over again, bring her.” He goes, “Oh, no, she’s here.” “Where?” “She’s out in the truck [with her mom]. Can I bring her in?” I said, “Yeah, of course.”

So he goes and brings his little daughter in. He just was obsessed with this dog. The two of them just sat there. I was getting a bit panicked because I had a deadline, and Bob wasn’t interested in talking about the artwork. He just wanted to watch this dog.

The other thing that I thought summed him up, once when we were doing Biograph, Bob was explaining to me about the songs. He said, “I don’t know where these songs came from. People thought they’ve got messages and everything, you know? People read so much into ‘Positively 4th Street,’ but I wrote it in a coffee shop on 4th Street. That’s it.”

If it had been anyone else, I would say, “Oh, yeah, right.” But knowing Bob, he didn’t know where it came from. And I thought that was a beautiful thing.

I had to go to his house in Malibu to meet him about something. I remember Jeff said to me, “Well, it’s kind of weird. He’s on Point Dune”—which is some of the most expensive real estate in all of California—“When you get to his house, you won’t think it’s a house there. There’s a chain link fence up. It looks like a building’s going to be built there, but it’s not [there yet]. You’ve got to go through the chain link fence, and you go down the path, and there’s a little building. In there there’s this Vietnam vet that Bob knows. He used to be an acid head. You’ve got to go up to him and he’ll let you go down to the house.”

It really was disconcerting, because you couldn’t see anything. You only saw this kind of empty lot, and you could see the ocean past that. And I thought, “Where’s the fucking house?”

And I got a warning. “When you go down, you’ve got to be very careful because Bob’s got these dogs. They get excited.” So I go down this thing, and these dogs, literally the Hounds of the Baskervilles, come out running at me. Scared the shit out of me. I think his wife called the dogs off.

Down where the house was, it’s beautiful. He doesn’t want people to know he’s there. He just doesn’t want to be bothered with people. And I can understand that. I mean, he didn’t want to be famous. Out of all the people that I’ve worked with, and I’ve worked with some big people, he is the most interesting. Like, I worked with Duran Duran, and I love those guys. But they’re very aware of everything. They’re very aware of their celebrity. They’re very aware of style. Bob doesn’t care about that.

I’ll end with this story. I said to Jeff Rosen, “Do you think Bob would sign a letter of support for my visa to live in the U.S.?” He goes, “That’s going to be a tough one. I don’t think you should count on it. The last one he signed it for was John Lennon. “

So a couple of days later I get a call from Jeff. He goes, “Bob signed your letter.”

I wish I’d kept it. I mean the fact that the last person he signed it for was John Lennon and he didn’t do that kind of thing shows how much respect he had for me as a collaborator. Because, you know, I took his opinion seriously, but I didn’t just say yes. I disagreed with him on some things.

I did a series of paintings. Someone said to me, “You should reimagine your album covers and do them as canvases.” So I did. I painted them as like four-foot by three-foot paintings. I did the Bow Wow Wow cover, I did The Cult, I did Duran Duran. The first one I did was Biograph. I called it Biograph Unfinished, because I didn’t finish his eye. I purposely wanted to make it different.

After I finished Biograph, Jeff Rosen said to me, “Bob has got something for you. When can you come up to the office?” So I went up to the office. Bob wasn’t there. Jeff gave me this thing—it was a signed copy of Biograph. It said, “For Nick Egan, thanks for making this what it is. You’re a star. Bob Dylan.” So I did the same signature on the painting.

Did Bob give you feedback on the Empire Burlesque or Biograph covers?

Not so much with Empire Burlesque, because I think it was a fait accompli. It was done, and they needed the cover out because they were in a bit of a panic. So Bob was like, “Yeah, great.” In all honesty, I’ve probably listened to Empire Burlesque once. I heard it when I did the art. I just never got back to it, because then I was thrown into doing Biograph, and that’s when I got into his catalog.

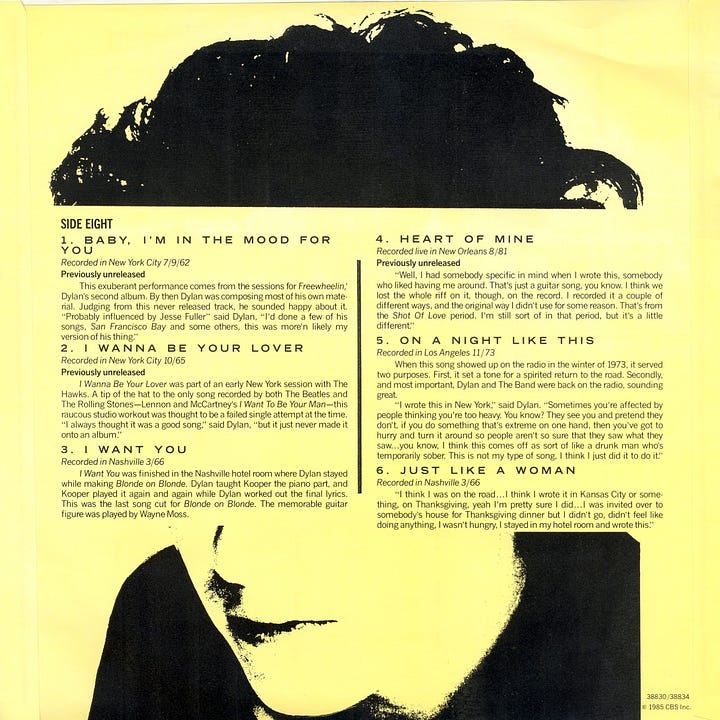

He was more involved with Biograph. There were a few things that he was really nitpicky on, especially the dust leaves with all the words. He was very particular about the way that looked. Biograph was his baby, really. He wanted that to be perfect.

Every time I saw him, he would ask me questions. “Why did you choose that picture?” “Why did you do that?” He wanted to know why.

I had the same experience with Oliver Stone. I did all the inside stuff for [the JFK packaging]. I got a typewriter from 1963 or 62. I typed everything on that, so it had all these mistakes. Oliver Stone was going, “Why did you do it like that?” I said, “Because that was a typewriter that people were using when Kennedy was assassinated.” He loved that kind of stuff.

And that’s what I love. I love the research. I’m not one of those people that goes, when someone asks me, “Why did you do that?” “Oh, just because I like it.” I’ve always got a reason. And I enjoyed that with Bob. He wasn’t dictatorial. He didn’t stamp his foot and say no.

My biggest problem with record covers was always the legal line. I’ve got more shit about that than anything else. Forget the cover. It’s “You missed the comma of the copyright thing at the bottom.” That’s what record labels care about. They are obsessed about it. If you don’t get the PNC right, and the little thing on the back that says copyright so-and-so, they go bananas. Believe me, that’s been the bane of my life for so many years, that little tiny thing at the bottom. I’m like, “Jesus Christ, who reads that shit?”

Unfortunately, it didn’t end well. When I was doing Drawn Blank with him it was like a job from hell, because he would show up suddenly and ask me to drop everything and go. An album cover is different. You’ve got a certain amount of time, you’ve got to get it done. Even he knows that. But with his book, he had all this time. So I wouldn’t hear anything for six months and suddenly, “Bob’s in town, can you meet him?”

It went on for over a year. I was having to go to Australia and all these things. It upset Bob that I didn’t drop everything. I did as much as I could, but I think Bob lives in Bob-land, you know? He doesn’t get what people’s lives are like, that they have other things to do. And I got well-paid working with Bob, but you can’t be over a year on one project. It was really difficult to get him to understand that. It’s not that it soured him, but I think it was a bit disappointing for him, because I wasn’t available.

I still love him. I think he’s one of the best people I’ve ever worked with. I certainly got the best stories out of working with him, and some of the best artwork.

Thanks Nick! Find more info on his work at nickegan.com. And thanks again to all the other interviewees who spoke with me for this weeklong ‘Empire Burlesque’ 40th celebration: Arthur Baker, Ira Ingber, Jon Paris, Vince Melamed, and Richard Scher. If you missed any of the entries, find them all here.

Such a cool interview. The mid-'80s were a strange time to be a new Dylan fan. I'm a bit younger than Nick and knew his name from reading liner notes so it was crazy to see him leap from post-punk to Bob.

Looking at your interviews about this period and seeing how he was really trying to reach out to my generation - with this artwork, when he worked with the Plugz, etc - has really enhanced my perspective of those times.

And I realize part of why I was drawn to Dylan was that he truly was a punk godfather.

I appreciate the comments you have all made. We are lucky that in this age of social media that we can see what people think in real time. back when I was designing album covers you really had no idea if people liked what you did or not. It was only in this past decade that I have really seen how my work has been appreciated even studied in art schools and universities around the world. Without doubt Bob is the most interesting artist I've worked with, he's an enigma and it wasn't until much later that I realised I was one of the few people he got close to. He was like no other, he didn't care what the label thought or the media. He knew how to use them when it was necessary. I am interested to know if any of you have visited the Bob Dylan Centre in Tulsa Oklahoma?