The Advance Man Who Announced Rolling Thunder to Small-Town America

"Bob came after me. He was restrained by a couple of security people."

Flagging Down the Double E’s is an email newsletter exploring Bob Dylan performances throughout history. Some installments are free, some are for paid subscribers only. Sign up here:

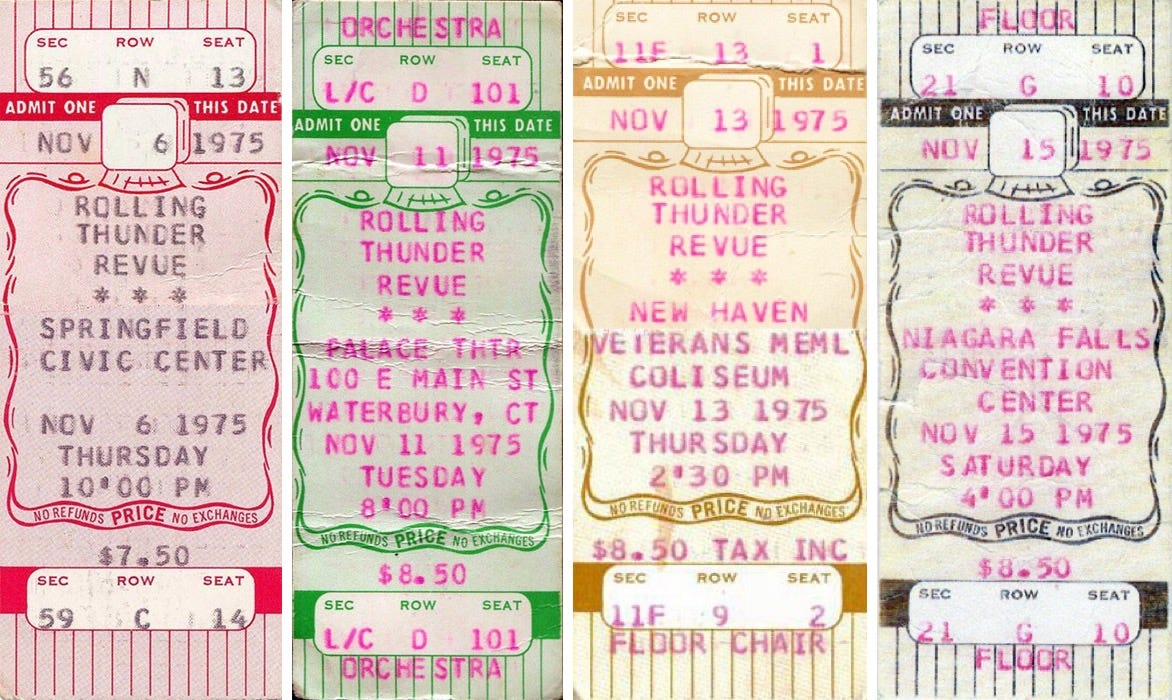

Part of what has made the Rolling Thunder Revue legendary was the spontaneity. In many cities, the shows would not be announced until a day or two before. Bob Dylan would play small theaters in out-of-the-way places, seemingly rolling into town on a whim to put on a show with his friends.

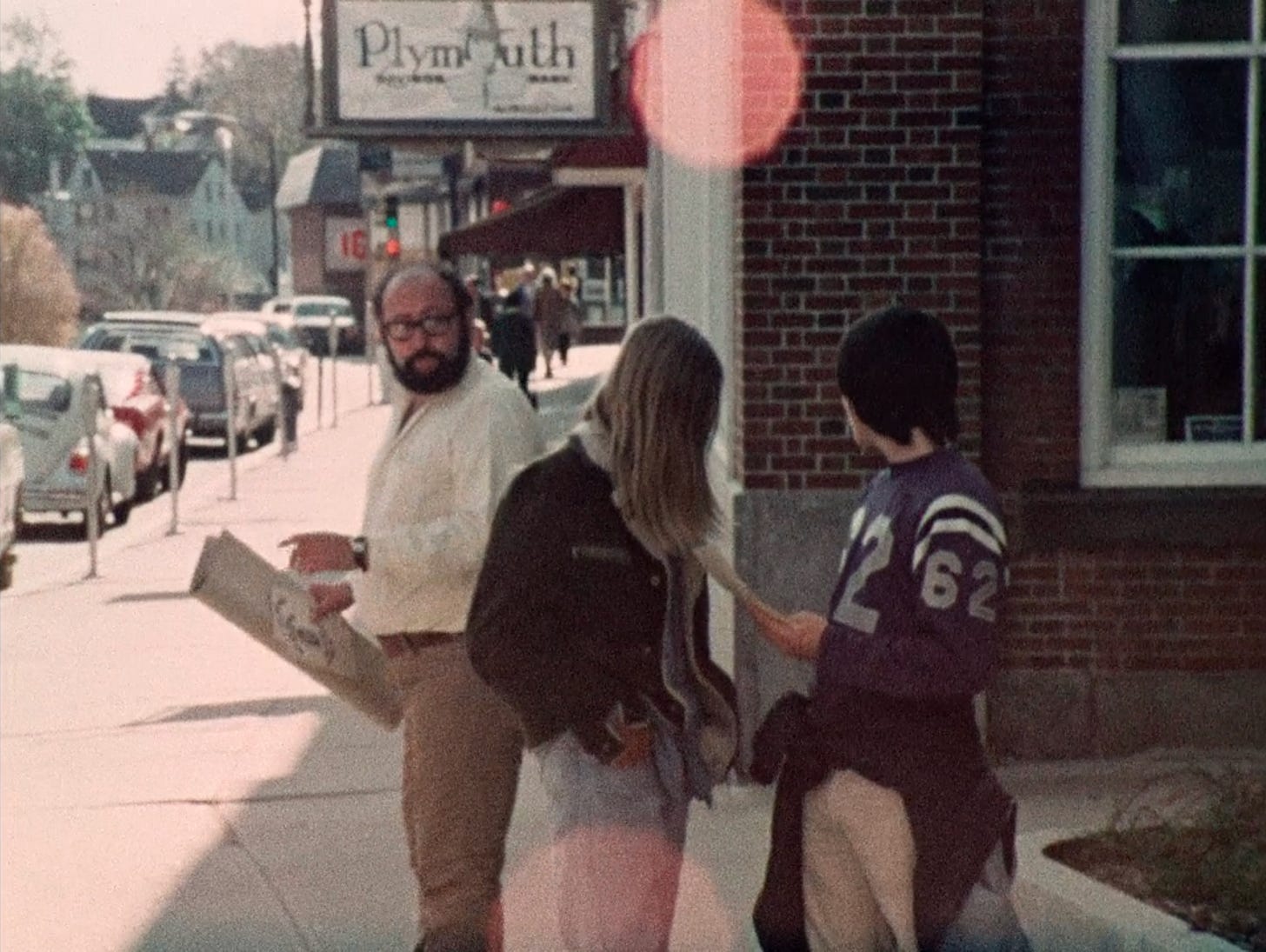

In the Scorsese documentary, you see footage of those shows being “announced.” It looks a lot like people handing out flyers to unsuspecting—and often skeptical—random locals walking by. Like this guy:

One of the people in charge of announcing and selling these shows on such short notice was Jabez Van Cleef. He would travel a few days ahead of the tour, trying to get the word out that—surprise!—Bob Dylan was about to perform in their town (with Joan Baez and Roger McGuinn, no less). Van Cleef was what’s known in the biz as an advance man, arriving ahead of everyone else to get things set up and sell tickets.

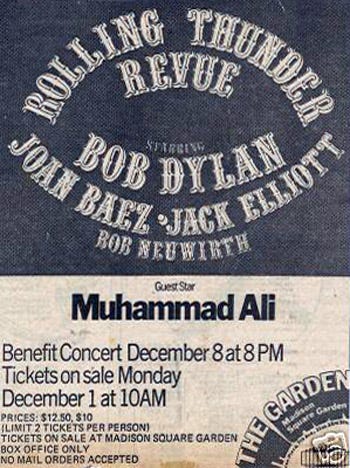

Today marks the 50th anniversary of the Madison Square Garden finale—one of the few shows Van Cleef could actually attend, with no more upcoming dates to advance. We spoke a few months back about the tour’s strange setup, and what it was like going town-to-town spreading the word about these surprise Bob Dylan concerts.

Oh, and about the time Bob tried to start a fistfight with him.

So much of the lore of Rolling Thunder is that tickets went on sale just a few days before. Correct me if this is wrong, but basically some guys roll into town with some fliers and say, Bob Dylan’s playing here on Thursday night.

Actually, it was two guys, sometimes three guys, and a girl. The girl eventually evolved into the cook and refreshment person for the crew. And the other guy eventually became the guy in charge of security for the stage during performances. His name was Mike something.

Mike Evans. I’ve interviewed him.

Mike was a college lacrosse player at a rather high level. I don’t know how he got involved in the tour. Probably through [Rolling Thunder production manager] Mikey Ahern. I have known Mikey Ahern pretty much my whole life. He and I probably met when we were six years old. We were both in a rather remote area in upstate New York. I went to Cornell and Mikey went to Syracuse, and then after a year or so, he transferred to NYU because he wanted to study acting and directing.

Since we were from poor or limited rustic beginnings, he needed to find a job. The job that he found was an outgrowth of his knowledge of carpentry. He was hired by Bill Graham to be the production stage manager for events at what eventually became known as the Fillmore East. That is the source of his interconnectedness with rock and roll crew people. So he was our source for knowledge about jobs.

I wasn’t looking for a job in the rock and roll business. I was just a kid that graduated from college and was looking around for what to do with my life. He told me that he had a preference for hiring people like me that didn’t know anything at all about the business, but that he knew that he could trust. So that’s how I got [the Rolling Thunder] job. I didn’t know dip about rock and roll crew. But it was fine.

Basically, our group of people preceded the arrival of anything else in whatever small or medium-sized place we were supposed to be preparing for a performance in. It started, as you probably know, in Plymouth, Massachusetts. We had gone up to Cape Cod, and we were in Cape Cod for about a week at a motel, while all of these people from California gathered.

That’s during the rehearsals that the band and Bob are doing?

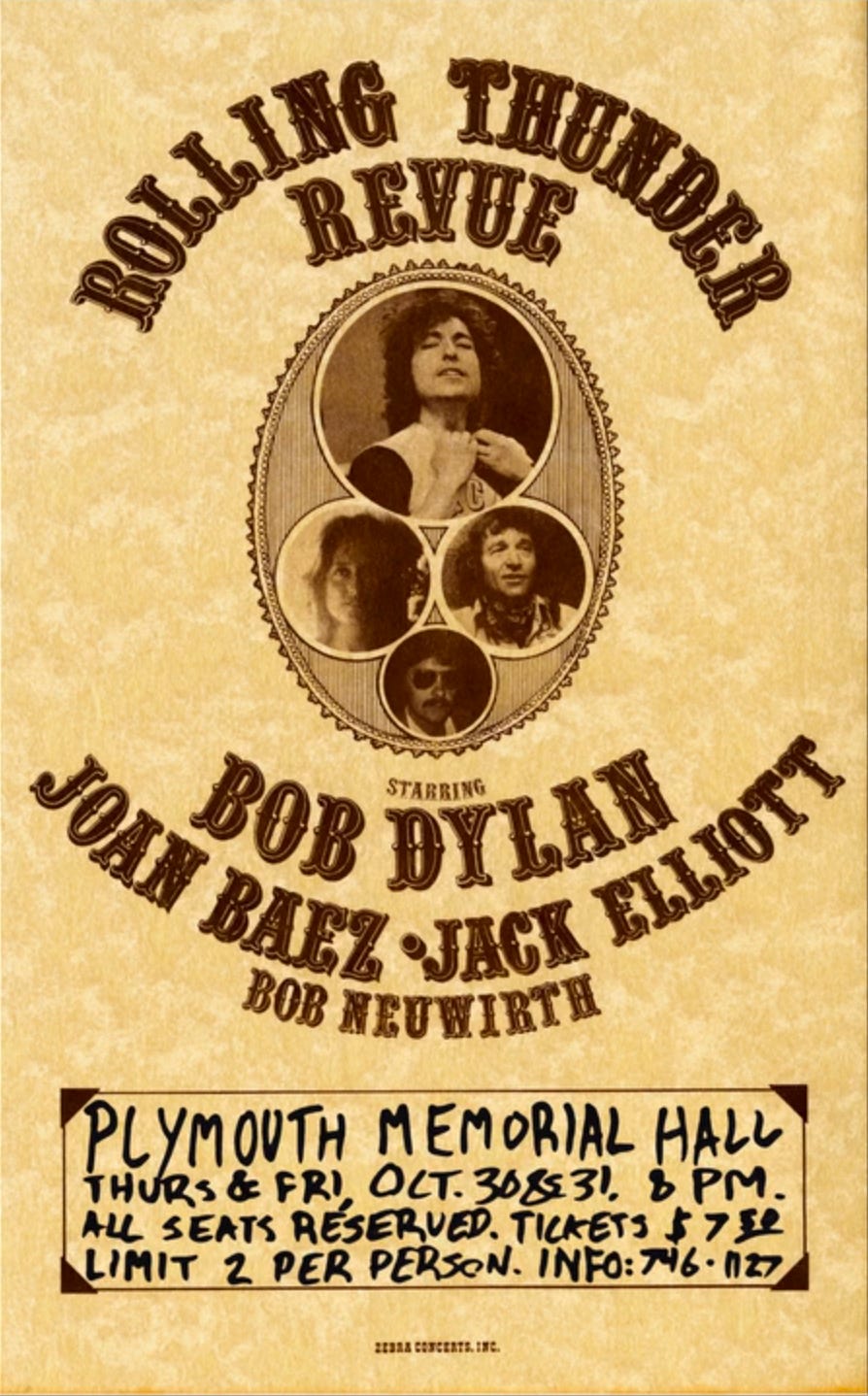

Yeah. I’m not sure where they were doing their rehearsals, because that wasn’t my charter. My charter was to assemble these various materials. Now, what materials are we talking about? We had posters. In the Scorsese movie, there’s a shot of a poster. In the bottom part of the poster, there’s a box, and it has handwritten information about how to get tickets, like what the address is or the telephone number to call or whatever. [Photo up top]

That handwritten material in that box was pretty much always written in by me, because the other people in the advance crew thought that I had more legible writing.

Probably they also didn’t want to do the tedious job of repeating that written material forty or fifty times over.

Is that how many flyers you would have for a typical show?

We had two things. We had those posters, but then also we had to go to a local quick-print place and get flyers made up. So usually we would make up three hundred or four hundred flyers, and we would go up and down the streets of the location, put ‘em under the windshield wipers of the cars, that kind of thing. We would put some of them up at the kind of places you would find a flyer, and that would be that.

But also we had these posters. We would put the posters on the actual venue building as a way of substantiating the thing. In fact, we would look for a police station or someplace like that and ask, “Where’s a prominent place where we can put this poster?” And explain why we were doing it this way.

Because you didn’t want people to think that it was a scam. If you went to radio stations, it was pretty hard to get them to believe that this was actually happening.

Just because it was so different than how they were used to these things?

Yeah. Nobody had ever seen anything like this before. I mean, why would a guy that can sell fifteen thousand tickets to a hockey hall decide that he wanted to play a hall with five hundred people in the audience?

Eventually there were a couple of hockey halls.

For those handful of bigger places, are you doing the same thing, or are those sold more traditionally?

No, that would be much more the conventional thing. I got the feeling that Bob Dylan didn’t really want to talk about that much. That it was a money thing that the promoters wanted to do.

Barry Imhoff had a sort of grandiose idea of himself as a promoter, but I don’t think he had much experience being a promoter. He was connected to Bill Graham, and he set up a company called Zebra Productions. They were the ones that paid our checks.

The biggest problem that they would encounter in pulling off their expected sequence of events was preventing the [local] promoter people from leaking the information about the event. In fact, it’s interesting that you’re living in Burlington, because Burlington was probably the biggest violation of the conventional sequence of events.

What happened?

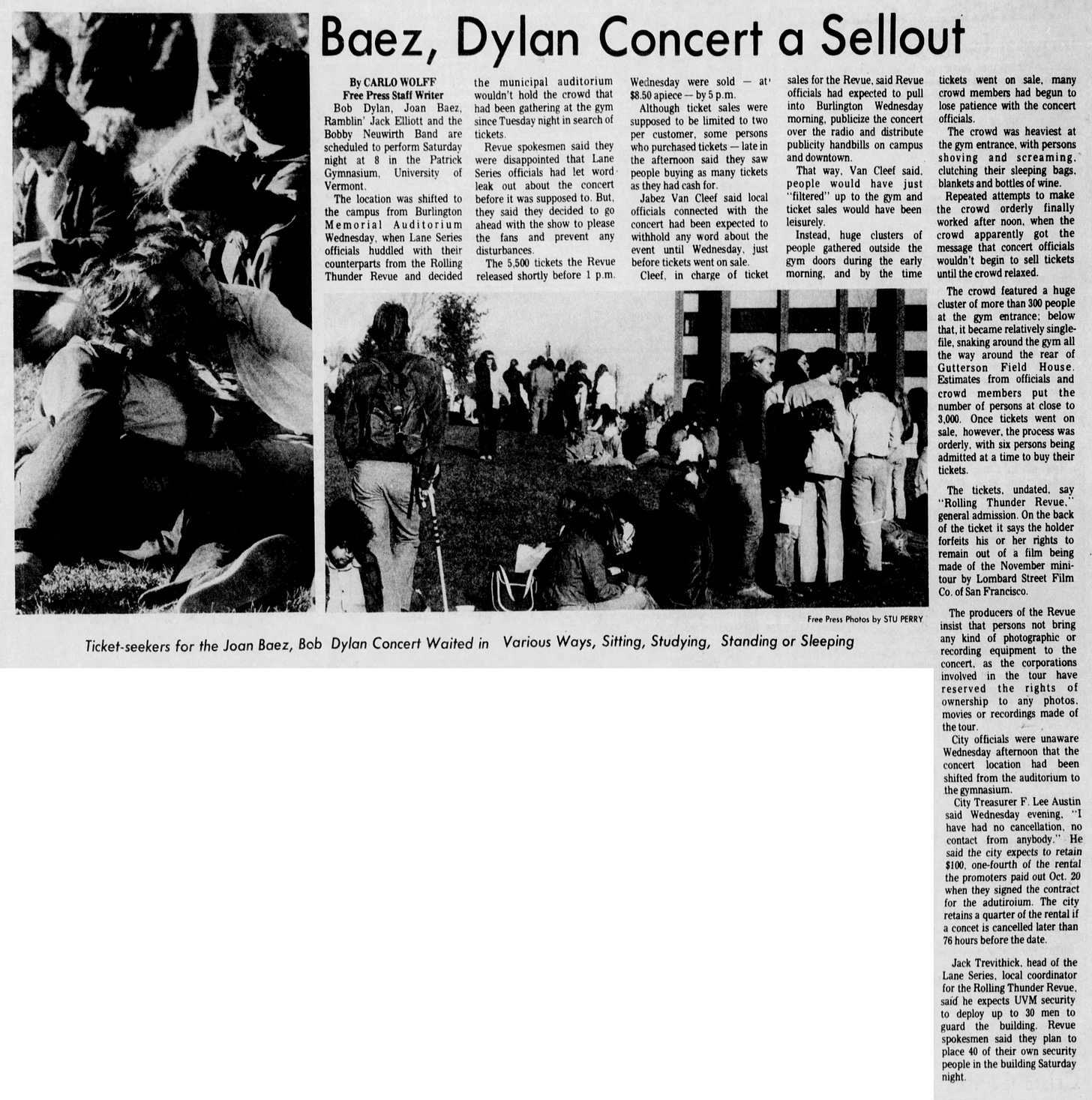

They leaked information. When they decided to release the tickets, they had a crowd of mountain man people waiting to buy tickets.

Mountain man?

People in pickup trucks. A lot of burly guys with beards. People from the backwoods of Vermont or Northern Vermont or maybe even Canada. There was a lot of them, and there were more of them than there were tickets to sell.

People got very concerned from our point of view because there was no recourse really. I mean, what are you going to do? You can only do one show because that’s all that the promoters have arranged for.

I’m not sure exactly how it got resolved [they moved the show to a larger (and lamer) venue], but we managed to escape with our lives. It proved to us that you pretty much had to be kosher about releasing information about the event beforehand.

My job was just to go and, in a controlled way, release the information beforehand. But not in an uncontrolled way five days before I got there.

Larry [“Ratso”] Sloman was there part of the time. He was a Rolling Stone writer. We had to avoid talking to him, because we didn’t want information about what we were planning to do to get out.

Did you encounter a lot of people, especially early on, who just didn’t believe you?

Yes. Now obviously, that type of response is going to diminish as you proceed along the tour. So that really only happened for maybe the first three or four shows.

I tried to call up radio stations in Rhode Island. They basically said, “Unless you can get me an interview with Bob Dylan and Joan Baez, I’m not interested.” So they were not necessarily believing what we were trying to do. For all they knew, I was just somebody that was hoaxing them. It didn’t matter that we’d already done the thing in Plymouth.

Were you ever actually at the shows, or were you always a city or two ahead of wherever the concert was that night?

Pretty much. I might get the beginning of the first show [in a city], but it was usual that I was off to the next place. That’s what being an advance guy is all about. Honestly, it was kind of fun, because I didn’t really want to see the same show a million times anyway.

Given that you’re always a few days ahead, were you having much interaction with Dylan himself or the musicians?

Somewhere along the line, maybe Rochester, they decided that we should generate a feeling of family. We should bring the crew together with the performers in an event that was just for us. And they had a party at a hotel.

I remember going to that party. Bob Dylan was at the party, and he wasn’t particularly outgoing and friendly to the people that he was supposed to be generating family vibes with. I guess it was because I was sort of staring at him or something, but he didn’t like my demeanor. He basically came after me. He was restrained by a couple of security people.

Wait, he physically came after you? Like he charged you?

It was more like, “Do you want to go outside?” That kind of thing.

I didn’t want to get in trouble with the boss, so I learned my lesson and avoided the whole situation.

Was that the first time you’d actually met him?

Yes, that was the first time I met him.

Was it the last time you met him too?

Yes. [laughs]

I can only compare, because I also met Joan Baez, and I also met Joni Mitchell when she joined the tour. Most of the performers were friendly and nice people, but Bob Dylan was a little standoffish. Not just to me, but to pretty much everybody.

It was sort of counterproductive in terms of the way that they wanted to generate a family feeling on the tour. If you say that the reason he’s doing the tour is so that he feels closer to his audience, then you would expect more camaraderie. But it wasn’t happening. Or at least it wasn’t happening with me.

You may have been at a disadvantage. You’re not really traveling with the tour. You’re traveling just with one or two other people, not in the group with everyone else.

All true.

Eventually I got the job of going out the following day and buying newspapers and scanning through to get any reviews. That meant that I had this repository of press information that could be used to create a sort of master scrapbook for the whole tour.

They had a commercial artist guy in an office in New York. He and I put this book this huge book together. But that was further on down the road.

Was that guy Tom Meleck?

That’s who it was. Tom and I worked on that book together.

How are you getting newspapers the day after a show? Because wouldn’t you have already been in the next place by then?

It was spotty. I occasionally would ask the catering lady, the lady that had been with us in the beginning, to get the thing and bring it to me.

The goal of the book was what? It was presented to Dylan, to the production?

I think it was the kind of thing that Barry Imhoff wanted to do to ingratiate himself with Bob Dylan.

So if there was a negative review, would you quietly keep that out?

Oh, yeah. It was that definitely that kind of thing.

I don’t think reviewers, generally speaking, knew what to make of this whole thing. Because it was called a Revue, and it had this atmosphere, in a deeply American way, like the circus coming to town. You didn’t really know what to expect. Sam Shepard was on was on that tour. I mean, of all people. Sam Shepard!

It strikes me if you just listen to the Dylan sets, like the ones he’s released, it just sounds like a Bob Dylan concert. An hour and a half or whatever. But if you find a tape of the entire show, with everyone else’s performances, it’s like four hours long!

I know. If somebody gave you something that you needed to do after the show was over, you had to sit there and wait.

So how many shows did you actually attend?

Maybe ten.

Madison Square Garden was the final night of that first leg. You must have been at that show. There was nothing else to advance.

Yeah, they gave us tickets to give out to people. I gave them out to friends of mine.

Was this just a kind gesture, or were they actually having trouble getting the seats filled?

I think it was a kind gesture because it was the end of the tour. They pretty much filled that place up.

Were you around or involved in the 1976 leg of Rolling Thunder?

No. And I can see why. I mean, the notion of being secretive about it didn’t have quite the same impetus.

It’s pretty much all big places that they probably announced a month or two in advance.

They were very idealistic in the beginning, but then little by little the siren call of the money led them to expand the number of seats.

Someone told me Bob was losing money hand over fist in that New England leg. It’s a huge production he’s bringing to some out-of-the-way small town. The next year, he needed to make up what he lost from the first part.

I’m trying to remember what the per diem were. I was getting paid three hundred and fifty dollars a week, and then there was a per diem that was thirty dollars a day. Something like that.

Would that have been industry standard back then? More generous? Less?

I think it’d probably be a little bit more than industry standard. They wanted people to be in for the count and loyal.

So were there any other memorable moments or stories from your time advancing Rolling Thunder that we haven’t hit on already?

It was weird watching that movie and seeing Sharon Stone. I couldn’t fathom what the hell that was all about. There was nothing in that movie about the crew. And I wish there had been, because the crew really had to put up with a lot.

The one authentic thing for me was seeing my own handwriting on screen. I felt pretty good when they showed that poster.

Thanks Jabez, and happy final day of Rolling Thunder 50 everybody! Rolling Thunder 50 Part 1, that is. Part 2, the 1976 leg, next spring…

Nothing against Sharon Stone, but that sequence with her was a bit clunky in the overall showcasing of that tour.

The best “Isis” ever, I declare. Dylan with his greatest pipes, and so happy to be there. Just, seemingly, so happy in general.

Thanks for all of these insights. Continually.

These interviews are all well and good but when are you going to to get Van Dorp? 😉