Rolling Thunder XIV: Cambridge

1975-11-20, Harvard Square Theatre, Cambridge, MA

Flagging Down the Double E’s is an email newsletter exploring Dylan shows of yesteryear. I’m currently writing about every show on the Rolling Thunder Revue. If you found this article online or someone forwarded you the email, subscribe here to get a new entry delivered to your inbox every week:

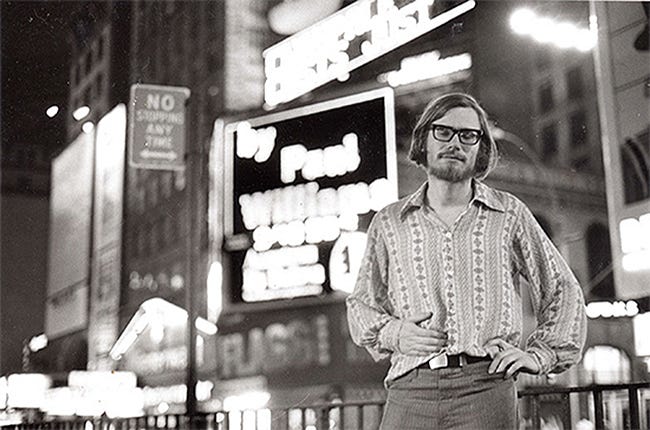

If you've read much about Bob Dylan, you've likely encountered the work of Paul Williams. Williams was among the first generation of rock journalists, founding Crawdaddy in 1966 (that's a year before Rolling Stone). The magazine was particularly inspired, he said, by a desire to cover music like Dylan’s new album Bringing It All Back Home. He remained a Dylan fan and scholar throughout his life, writing a number of books, including the three part series Bob Dylan: Performance Artist, in which he goes year-by-year through Dylan’s career as a singer and performer, both on record and in concert.

In his chapter on Rolling Thunder in his second book, 1974-1986, The Middle Years, he singles out one performance as the ultimate high point: Cambridge, MA, November 20. More than that, he singles out one song from that show: "It Ain't Me Babe." So I thought for today's newsletter, I'd excerpt some of his writing on that single performance. As anyone who reads these newsletters regularly will recognize, his writing style is extremely different from mine, so his intense focus on one song at one concert offers a different lens through which to view this music.

While you read, listen along to the recording of this song. You might not hear all the same things Paul did. I don't always myself. But I'm always glad he did.

Paul Williams on “It Ain’t Me Babe” from Cambridge MA 11/20/75:

There are many kinds of freedom; this song has often had a particular edge of "freedom from" - and a bite to it, a bitterness along with the humor, suggesting that the freedom is an uncertain one, still being fought for. That is not the case in the 1975 performances. The 1975 song is about spiritual freedom, that is, freedom that is not "from" or "of" any person or thing, but rather a freedom spontaneously experienced from within, a sense or sensation of the breath of the divine and of the unlimited possibilities that exist within the limits of the immediate situation. What I hear expressed in this performance, quite simply, is Dylan's joy at playing music. It is the band, the other people he's playing with, who most immediately make this possible, and so he and they are here celebrating the freedom they give each other.

No one is playing charts. No one is playing it safe. Everyone is creating at the very edge of his or her individual abilities and imagination, as part of a difficult collective undertaking, and they love it. And what they are producing together is, in my opinion, a work of art: a gestalt created of their skill and their interaction and their joy, that in turn brings joy and some kind of profound, enduring nourishment to its listeners, this evening and, thanks to the magic of recording, maybe forever.

This kind of ensemble creativity is not improvisation in the jazz sense; listening to a number of different performances of "It Ain't Me Babe" from the 1975 tour I hear the various musicians playing approximately the same musical phrases at the same times and for similar durations at each performance; clearly they're playing something that was worked out in detail in rehearsals before the tour. And yet each performance is truly different from the others. A simple mechanical concept of "performance" might lead us to think that if the form of the piece doesn't change, but they sound and character of it does, the only variable music be how well the musicians execute the work on a given evening.

This mechanical model fails, however, when I listen to "It Ain't Me Babe" from New Haven, 2nd show, 11/13/75, and from Bangor, 11/27/75, and find that both performances lack some of the moments I most love in the 11/20/75 one - and yet both are very good on their own terms, and different enough in their nature that something would be lost by choosing only to listen to 11/20 because it's the "best."

…

But what audible characteristics can I point to that distinguish the 11/20/75 performance of "It Ain't Me Babe" from its aforementioned Rolling Thunder brethren. Well, right from the start, the lead guitar intro sounds different all three times, and so does Dylan's voice when it comes in. Mick Ronson (lead guitar) may actually be in a different key at least one of the times, and certainly there's a variation in the little melodic figure he plays, as though he's got a framework in mind but within that framework he's totally free to improvise, and in fact he's expected to come up with a slightly different twist each time. On the other hand the difference in the lead guitar once the singing starts sounds more like it has to do with the sound mix - I think he's playing the same riff, but one time it's dominant (11/20) and another time you can hardly hear it. And doesn't it seem likely, in this kind of freewheeling performance, that that in itself could help set the mood of the performance, musicians and singer taking off on different tangents depending on how much leadership the lad guitarist takes, which in turn may depend not only on his mood but on the acoustics of the hall or the stage monitors or the vagaries of the mixing board? And Dylan's voice: Bangor, Maine, he sounds hoarse, and so he holds himself and his voice differently, applying just as much energy and imagination and soul to the song but putting it in different places, making the best use of what he's got to work with (also in Bangor he sings "I told you I'm not the one you need," the extra words seeming to reflect a particular experience he's just had or a way he's feeling, like a cue or clue to himself and the musicians to push the song forward along a new, unique angle of attack).

Stoner's bass playing also sounds different to me each time; my mind says he must be playing roughly the same part, but on 11/20 there's a magical energy to it, skipping, lyrical, whereas in New Haven he's right there but not leaning into it with the same adventurousness, and in Bangor he sounds laid back, almost lugubrious (it's weird, and it works). The climactic lead guitar solo that dominates the fourth verse of the song (three verses with words and then one that's pure music) is like a connect-the-dots puzzle that's done in the same order each time but the lines are fatter or thinner and twist in odd directions between dots and so the three pictures end up looking radically different. When I'm comparing these solos to try to understand 11/20, the others sound tentative and inadequate, but when I listen to them for themselves each has a character and power and charm of its own, entirely appropriate to the performance it grows out of. So there is improvisation, and accident, and personal expression which instantly becomes group expression, and infinite variation within fixed form, and finally, and above all, this collective commitment to a felt purpose, a cause, a fugue, an unspoken awareness that something is present here between us and we have this one fleeting opportunity to catch it if we can.

I'm sure I've listened to 11/20 (IAMB) a hundred times in the last few days, and I can't seem to exhaust it, can't wear it out. Is that T-Bone Burnett on second electric - sounds like amplified slide - guitar? The man's a crazed modest lilting romantic phenomenon. The sound of this performance is nothing like the sound of "Isis" or "Never Let Me Go," although all three are solid rockers. I've never felt these particular rhythms anywhere else in the universe, and I can't get enough of them. Mick Ronson achieves immortality (group effort though this may be) with this evening's guitar solo not just what he's playing but (like Stoner on bass) the way he's playing it, something about the energy of fingers (or pick) impacting strings, personal and inventive as your lover's touch, the music rises to crescendo and descends (just as energetically) just far enough to be embraced by Burnett and company and turned into ever-widening ripples of blissful circular sound, joined in new crescendo by Dylan's harp (provoking the audience into wild applause that should be for the guitar solos but isn't), and settling gracefully and raucously back to earth. Whew. And that's just the second song of the set. (They go into a "Hattie Carroll" that's almost as good).

If you don't already have 'em, Paul Williams' three Performing Artist books are essential live-Dylan reading. I think they're all out of print, but used copies aren't expensive. (And when you're done with those, peruse a short excerpt from a fourth volume he'd begun work on before he passed).

Rolling Thunder XIV: Cambridge

The Venue

The tiny Harvard Square Theatre, which seats only 1,850, is one of the smallest places on the tour. A visit from the Rolling Thunder tour must have been a great night for the venue, but it wasn't as important to music history as another night the previous year. A young songwriter opened for Bonnie Raitt at the Harvard Square Theatre on May 9, 1974. Local music critic Jon Landau attended the show. Soon after, he famously wrote about his experience that night: “I saw rock and roll’s future and its name is Bruce Springsteen.”

It became one of the most famous sentences in the history of music criticism, and Landau would go on to manage Springsteen. Bruce called it “one of the greatest lifesaving raves of all time” in his memoir a couple years ago, adding, “It has always been taken somewhat out of context, its lovely subtleties lost. But who cares now! And if somebody had to be the future, why not me?”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Flagging Down the Double E's to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.