Protests, Makeup, and a Whole Lotta Grateful Dead in Tour '74's Penultimate Stop

1974-02-11, Alameda County Coliseum, Oakland, CA

We’re almost there. On this date 50 years ago, Tour ’74 made its second-to-last stop, in Oakland, California. One reviewer called it “the event more anticipated, publicized, and ticket-scalped than any in Bay Area popular music history.”

Oakland being in the San Francisco area, a whole host of local bands made it out: Jefferson Airplane, Santana, the Doobie Brothers, Boz Scaggs, Van Morrison (not a local but apparently still in town after playing at the Winterland a week before—he covered “Just Like a Woman”) and, of course, the Grateful Dead.

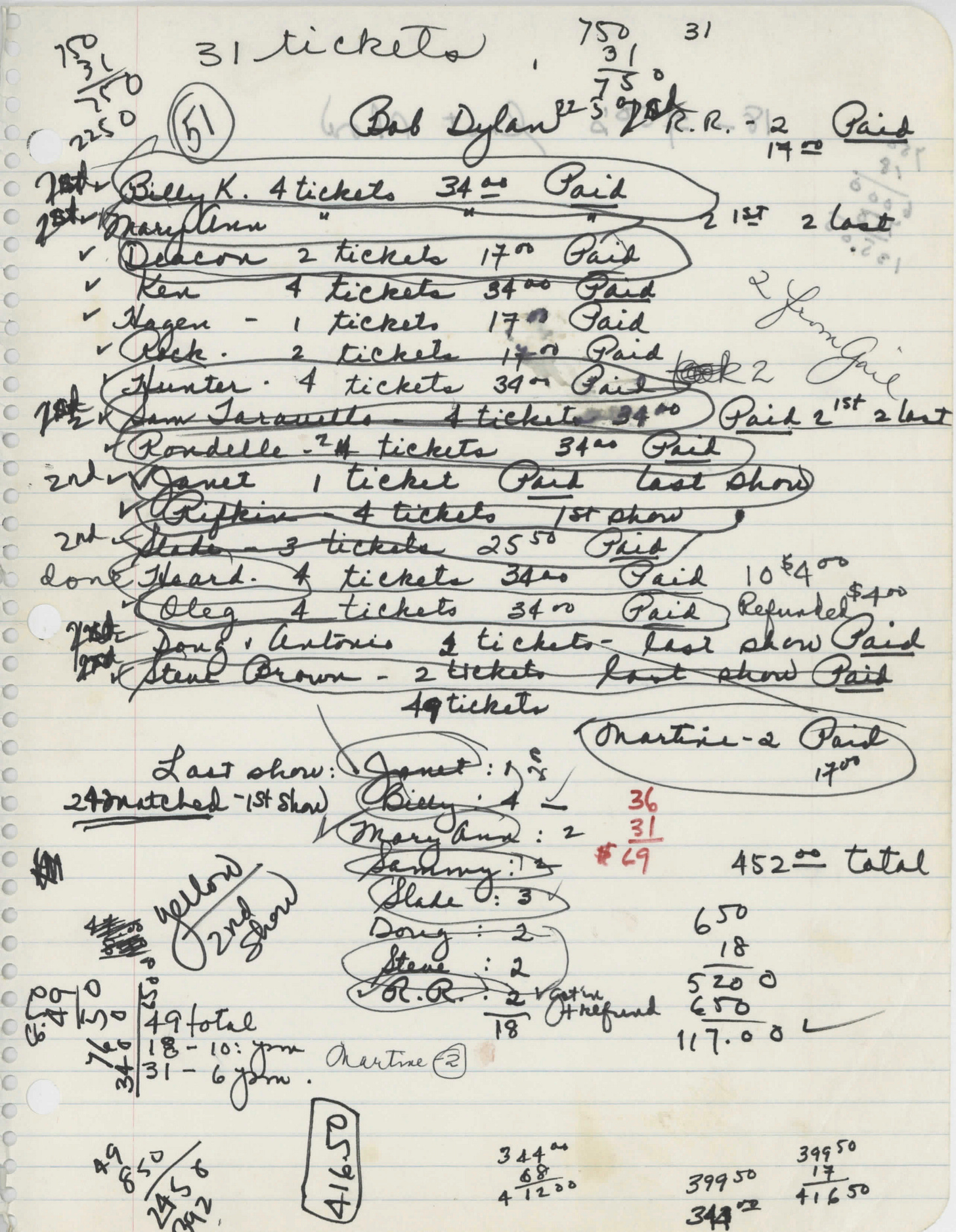

Friend-of-the-newsletter Jesse Jarnow shares this page of Dead ticket request notes from the Dead’s office files. Dead associate Sally Dryden kept track of the band-and-crew’s requests (51 total) on this chaotic scribbled notebook page. And that wasn’t even all of them; a local newspaper reported they requested over 200 tickets total (they had to settle for 100).

You can see Dead drummer Bill Kreutzmann and lyricist Robert Hunter (Bob’s future co-writer) on this, along with a bunch of crew guys. Jerry Garcia, who was also at the show, must have been among the 49 other tickets (his review: “It was an event, and all the old freaks came out for it”).

These two Oakland shows, like several before them, came with controversy. In this case, the controversy started close to home. Mimi Farina, Dylan’s compatriot from the early Village folk scene (and Joan Baez’s younger sister) wrote an open letter to Dylan in the San Francisco Chronicle, after having earlier announced she would picket the tour. She criticized his “desertion” of political activism, the high ticket prices and, especially, the widely-circulated rumor that Dylan would be donating part or all of the tour’s profits to Israel. “In a time of war, when God is on neither side, clearly both sides suffer spiritually and physically,” she wrote “To financially encourage one side or another is to encourage war itself regardless of who starts it." She added, “The money you earn is the money we are willing to give you…if it is going to support the taking of more lives, we should know that before we buy our tickets.”

Dylan, for his part, denied the rumors, saying “That’s like asking if I’m doing this tour to raise money to go to the moon in 1983.” And Farina, in the end, did attend one of the Oakland concerts with her sister, though she gave it a lukewarm review: “I brought Kleenex with me. I was ready to cry. But I never had an inkling of emotion, of the poetry behind the songs.”

Also on hand: A whole lot of music journalists. Rolling Stone was still based in San Francisco (it would move to NYC in 1977) so big names like Ralph Gleason and Greil Marcus and Annie Leibovitz were out. Marcus wrote a terrific review of the Oakland shows for Creem. I like this section, where he explains how the show impacted him:

I had read a lot about Bob Dylan’s tour with the Band before it arrived at the Oakland Coliseum Arena February 11, just before the close-out in Los Angeles; on paper, I knew all about it. I knew precisely how the show was structured: Dylan & Band, Band, Dylan & Band, intermission, Dylan solo, Dylan & Band, “Like a Rolling Stone,” encore. With a few trivial variations, I knew what songs were to be played and in what order. I knew how the crowd would react and to what: they’d go wild for “Even the president of the United States must sometimes have to stand naked”; a few jerks would yell “We Want Dylan” when the Band played. I knew well-timed lights would cue the audience response for “Like a Rolling Stone,” and that the song would be referred to as “an anthem” in the papers the next day; I knew that matches would be lit to solicit the encore. It seemed like a set-up. I was looking forward to giving Bob Dylan a standing ovation when he walked out, but I was damned if I was going to light any matches.

What the press did not prepare me for was the sound, the singing, the playing, and the impact. I wasn’t prepared to hear “Rainy Day Women” come store-porching off the stage as a big, brawling Chicago blues; for the black usher dancing down the steps of the hall, waving his flashlight and singing “Knock, knock, knocking on heaven’s door”; for the delight I felt when Robbie Robertson and Rick Danko rushed a single mike for a chorus just like Paul and George in A Hard Day’s Night. I wasn’t prepared for one bit of what mattered about the show, and I doubt if anyone else was either.

Love the image of the usher dancing down the stairs, waving his flashlight while singing “Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door.” Wish Annie Leibovitz got a photo of that! (She may have been there in a non-professional capacity, as I’ve unfortunately never heard of any Tour ’74 photos by her, even though she would shoot Bob a few years later.)

Rolling Stone’s Ben Fong-Torres, who had been there since the very first show in Chicago, compared and contrasted the two Oakland shows:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Flagging Down the Double E's to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.