Last Night in Brighton (by Jack Walters)

2025-11-07, Brighton Centre, Brighton, UK

Flagging Down the Double E’s is an email newsletter exploring Bob Dylan performances throughout history. Some installments are free, some are for paid subscribers only. Sign up here:

Last night, Bob Dylan played Brighton for the first time since 2002 (with Nick Cave spotted in the audience!). Jack Walters reports in:

At 84, Bob Dylan has lived a thousand lives and has worn more masks than a Venetian masquerade ball, putting the lecherous Byron to shame. And yet he is still on the road; his Coyote spirit alive. One gets the impression that Dylan has, somehow, performed in Solomon’s Temple, aboard the Arbella, with Bob Wills at one of Burt “Foreman” Phillips’ County Barn Dances, and at the March on Washington—well he did. But you get the point: Dylan seems to contain all these references. Wherever and in whatever century, Dylan performs. And we, the audience, are a station to his Calvary or, prosaically, witnesses to his journey, meeting and leaving him in shadows, wondering if performing, at its most dignified, truthful, sublime, is, paradoxically, best rendered in distance—if possible, absence.

When Dylan last performed at the 4500-cap, Brutalist-designed Brighton Centre in 2002, he opened with “I Am the Man, Thomas,” a jaunty bluegrass number about Thomas the Apostle, bringing Caravaggio’s The Incredulity of Saint Thomas to life with light, drama, beauty. Anyway, that was then (when Dylan was a cowpoke), this is now (when Dylan is half-hidden).

Dylan, along with the band, suited and booted, more elegant than ever, walks out to a recording of “La damoiselle élue (Hania Rani Rework (After Claude Debussy))” by Víkingur Ólafsson, which, due to some prior research, has a connection to Walt Whitman (do I need to say that he was the inspiration behind the song title, “I Contain Multitudes”?). In 1887/88, Debussy set British Pre-Raphaelite Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s poem “The Blessed Damozel”(1850) to music; the text was translated by the French writer Gabriel Sarrazin (1853–1935), who wrote an article on Walt Whitman, published in La Nouvelle Revue on 1 May 1888. In January 1889, Sarrazin sent a copy of the well-received article to Whitman who, after he got the piece translated by two people and read each translation, pronounced it to be among the “strongest pieces of work which Leaves of Grass has drawn out,” according to Horace Traubel, a biographer and friend of Whitman. Whitman wrote to Sarrazin, and the two continued to correspond until Whitman’s death. Whitman’s “I contain multitudes” is from Section 51 of the poem “Song of Myself” (1855), published in his collection Leaves of Grass. Most likely, Dylan likes the piece of music.

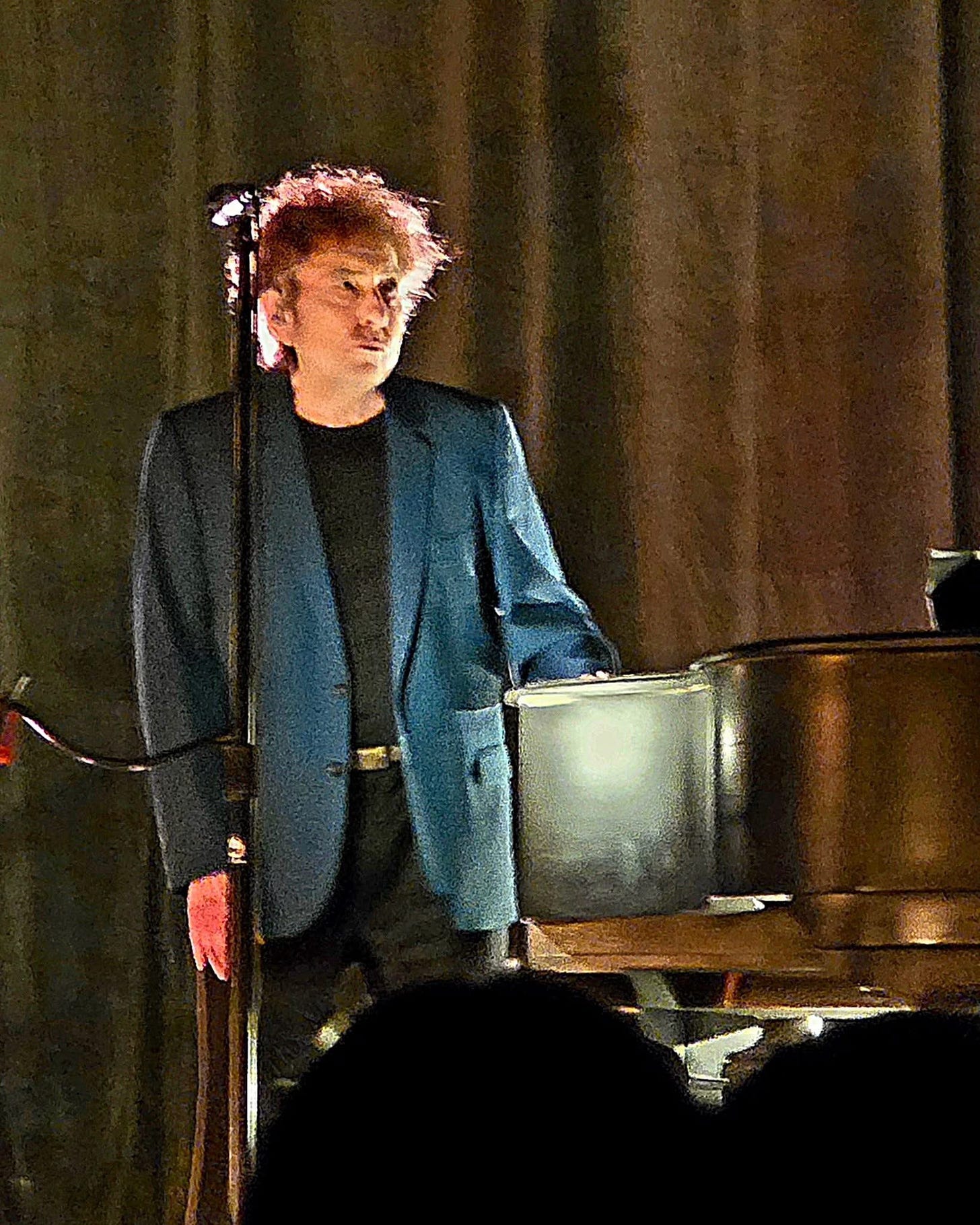

Anyway, “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight” starts out as an interminable jam—notes curling and twirling, dying in the ether, a cacophony of noise, like some Modernist prelude that nobody understands, but, surely, there must be a melody buried beneath the dissonant racket, right? —which reminds of the lengthy intros of “Watching the River Flow” in 2022 —except now Dylan, fancying his chances as some Elmore James without the flash or flair, sting or bite, is playing an electric guitar. Or, rather, producing some bum notes that suggests he doesn’t know what the hell he is holding, before proceeding to strangle the neck of the guitar like the serial killer in Hitchcock’s neo-noir thriller Frenzy; until, that is, bored of death, turns around and, instead, belabours the piano keys. As he starts singing about being your baby, the crowd cheer in recognition of hearing his voice, or in recognition that they might be in for a long night. And you’re thinking: Dylan can still confound you in 2025. Damn him.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Flagging Down the Double E's to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.