How Bob Dylan Found New Melodies Inside “Hard Rain”

An excerpt from 'What Did You Hear? The Music of Bob Dylan' by Steven Rings

Flagging Down the Double E’s is an email newsletter exploring Bob Dylan concerts throughout history. Some installments are free, some are for paid subscribers only. Sign up here:

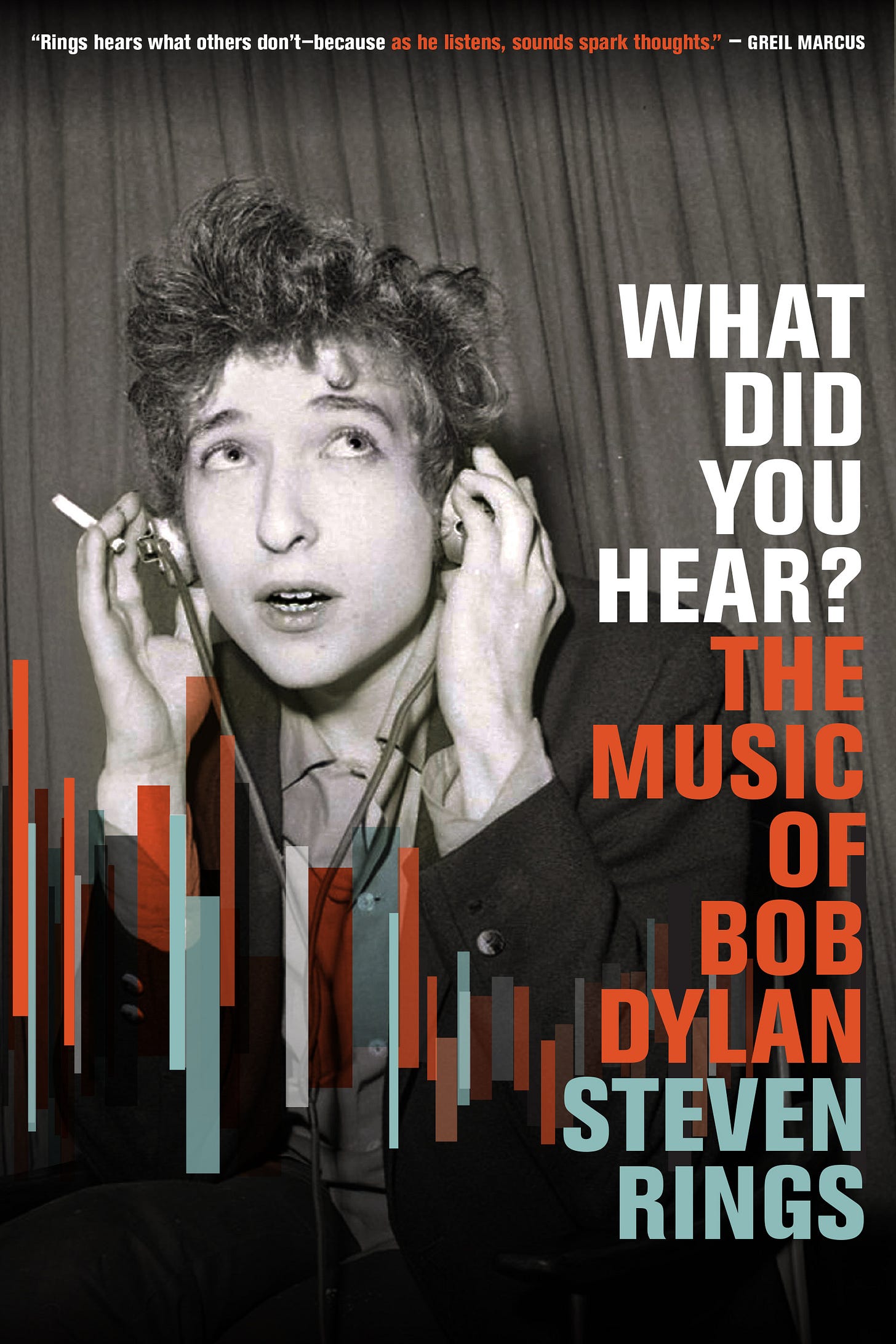

Longtime readers may remember that a few years ago, I asked a music professor to explain Bob Dylan’s oft-mocked “upsinging” to me. The professor, Steven Rings, broke down exactly what Dylan was doing from a technique perspective (without going so far as to entirely defend the practice). Now Rings has written an entire book. It’s called What Did You Hear? The Music of Bob Dylan and comes out later this month from The University of Chicago Press.

The key word in the title is Music. Unlike most books analyzing Dylan’s songs, Rings does not focus on the lyrics. He focuses on the sounds Dylan produces through his instruments: Guitar, piano, harmonica, and, first and foremost, voice. He delves deep to explain how exactly Dylan performs his songs, what musical sources he’s drawing from, and how his techniques have changed over the decades. It’s like Paul Williams meets music theory.

I found it a fascinating read. I don’t know any music theory really, but Rings makes it accessible even to a novice like myself. Helpfully, he includes a lot of audio examples so you can listen along to hear exactly what he’s describing. The book touches on many different songs, but one that gets extended treatment is “A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall.” He was kind enough to offer an adapted excerpt from that section to run here a few weeks before publication.

In the below excerpt, Rings writes about “Hard Rain”’s live evolution from the famous Nara 1994 orchestral performance into the beginnings of the 21st century, with audio clips so you can listen along.

The story of “Hard Rain” from the gospel era through the Never Ending Tour divides into two halves: before Nara and after Nara. By “Nara” I mean the three stunning performances of the song that Dylan gave with an orchestra in Nara, Japan, on May 20–22, 1994. These transformative renditions are beloved by fans. They also act as a hinge in Dylan’s approach to the song. Before the Nara concerts, he sang “Hard Rain” with a declamatory urgency, often deploying the bluesy, gospel delivery that he developed in the late ’70s and early ’80s. After Nara, his singing became far more lyrical and tender, infused with a kind of gentle wisdom and wonder. The awestruck reverence of the song’s early years returns. As for arrangements, in the before-Nara era, the song was typically part of the acoustic set, often solo, always performed in D, and relatively close to the 1960s arrangement as regards meter, groove, and form. After Nara, arrangements began to morph once again, taking on new keys, new instrumentation, new rhythmic feels. The Nara concert thus unfolded a new dimension of the song, teaching Dylan that it contained more potential than even he yet knew.

The Nara performance—the first and only time (thus far) that Dylan has sung with an orchestra—was part of the Great Music Experience, three concerts (all basically identical) funded in part by UNESCO, organized by British impresario Tony Hollingsworth, and broadcast on international television. [Readers of this newsletter will know the behind-the-scenes details from Ray’s excellent post on the concerts a couple years ago.] A vast array of musicians were assembled for the event, ranging from taiko drummers and a traditional Japanese orchestra to a motley assortment of Western artists, including INXS, Joni Mitchell, Jon Bon Jovi, Ry Cooder, Wayne Shorter, the Chieftains, and Bob Dylan.

The event would be easy enough to dismiss as a spectacle of 1990s globalist kitsch had Dylan’s performance not become so beloved by fans. Much of the rest of the concert veers perilously close to the new-age world music of Yanni or Kitarō, but Dylan’s performance with the Tokyo New Philharmonic Orchestra retains a singular strangeness and potency. Conductor Michael Kamen arranged three Dylan songs for orchestra—“I Shall Be Released” and “Ring Them Bells” in addition to “Hard Rain”—scoring them in the lush Hollywood style he had honed in his film work, as well as in his other orchestrations for rock musicians from Pink Floyd to Metallica. Asked in an interview if he had requested that Dylan sing a certain way, that he discipline his melodic invention and stick to a fixed tune, Kamen said “no”:

I think he’s just responding to the reality of the musical situation. The orchestra’s doing things in the music that he hasn’t heard for a long time. I brought things out that I’ve always felt were in the music. His chords are beautifully simple; his words are deliciously complicated and heartrendingly pure. I was just sort of painting pictures with the arrangements, illustrating his words as if it were a Bach chorale—which, after all, doesn’t have that many chords—and weaving lines inside and outside of each other to amplify the lines…illustrating the music in the vocal. And that inspired him to sing.

Kamen clearly based his arrangement on the 1962 studio recording, matching its metric details exactly. Dylan, so used to dropping and adding beats at will, has to follow the orchestra closely. Unlike his bands, the orchestra cannot turn on a dime to follow his metric whims. As a result, Dylan settles back into the pacing of the song as he had performed it for the microphone thirty-two years before.

Dylan sings with melodic focus and restraint in the first verse, establishing a template that he will gradually depart from over the course of the song. He sings the initial questions to the exact tune of the Freewheelin’ recording, and then establishes a new melodic shape for the answers. Listen to how the answers trace an up-then-down contour:

By contrast, the answers only descend in 1962:

Another crucial distinction from the studio recording is that the Nara Dylan leaves himself room to ascend gradually across the course of the song. On Freewheelin’, every verse tops out on the same pitch, a high E, which he sustains on the word “rain”:

By contrast, here is the first refrain at Nara:

Dylan is holding something in reserve: he only ascends as high as he did in the answers, to the B-flat right below middle C. This performance is in E-flat, and Dylan will eventually attain that pitch—triumphantly—as the song progresses.

He first touches on it in verse three, first at “my darling” and then several more times, climaxing at “died in the gutter” and “cried in the alley”:

In the final verse Dylan fully realizes the E-flat climax. He moves into the upper register with the fifth answer, eventually securing it as a kind of plateau. At this point he begins an oscillation between the high E-flat (bold) and that earlier, lower B-flat (italic):

5. Where the home in the valley meets the damp dirty prison

6. And the executioner’s face is always well hidden

7. Where the hunger is ugly, the souls are forgotten

8. Where black is the color and none is the number

9. And I’ll tell it and think it and speak it and breathe it

10. And reflect from the mountain so all souls can see it

11. And I’ll stand on the ocean until I start sinkin’

12. And I’ll know my song well before I start singin’

Note the gradual increase in bold over the course of the answers, as the E-flat plateau becomes more and more emphatic. The refrain then centers on the same charged interval between B-flat and E-flat, oscillating tightly between the two pitches at the final climactic statement of “it’s a hard rain”:

Cause it’s a hard, it’s a hard, it’s a hard, it’s a hard,

It’s a hard rain———’s a-gonna fall

The epic sweep of the whole vocal performance matches the Hollywood crescendo of Kamen’s orchestration. But Dylan’s fragile voice remains a sound apart, inassimilable to the professionalized ranks of the orchestra. This separation is made visible in the video of the performance by Dylan’s position at the lip of the stage, physically far from orchestra and conductor and dwarfed by them. The result is a figure/ground relationship that thrums with tension and risk: at any moment Dylan’s voice is entirely capable of violating the aesthetic contract of this occasion, this setting, this middlebrow musical arrangement. And even as it precariously follows the letter of that aesthetic contract, his voice in all its imperfection resists full assimilation to the musical code, the tightly regulated system of harmony, melody, and counterpoint fixed by Kamen’s polished arrangement. Dylan’s adherence to the script, his outward enactment of a mass-cultural epic narrative, paradoxically amplifies his difference-in-sounding. His tattered voice is an unsettling remainder, a literal dissonance, sounding apart from the festival’s euphonious representations of global uplift.

Many find the result deeply moving, as fan discourse and a glance at the YouTube comments for the video confirms. I suspect that this is in part due to the very dissonance I just mentioned, the fragility of Dylan’s voice in front of the professionalized orchestral mass. The result would hardly feel so heroic were it sung by a more conventional voice (imagine, if you dare, Michael Bolton singing it). Dylan himself knew that he had achieved something special in the performance, reportedly telling Hollingsworth that he hadn’t sung so well in fifteen years. He had moreover unlocked a new approach to the song, in two respects. First, he had discovered a new lyricism and tenderness in his delivery. In the 80s and early 90s, he had approached the song with fiery intensity, but now he sings it more gently, the parent’s affection for the blue-eyed son infusing the whole. Second, he had fully realized something that he had been working toward in previous years: a song-spanning vocal ascent. Both of these discoveries would reverberate in Dylan’s performances of “Hard Rain” in the coming years and decades.

Indeed, we can hear them in his very next performance of the song. On August 17, 1994, he sang it in Hershey, Pennsylvania, as the final number of the encore. Dylan plays acoustic, accompanied by Tony Garnier on bass and John Jackson on a second guitar. The tone throughout is warm, generous, and tender. Dylan carefully sustains his sung pitches, gingerly traversing the D-major scale, with nary a hint of a blue note. Here is a bit of verse 1:

The singalong at the refrain is especially touching. As at Nara, Dylan sings in his midrange for most of the song, gradually ascending. In the final chorus, Dylan completes this ascent with a sustained high D, holding it until the final moments of the word “fall,” when he tumbles gently downward. The performance thus traces the same song-spanning ascent as at Nara, which is remarkable, given its overall tone of unruffled lyricism. Nor was this a one-off. In Manchester, England, the following April 5, Dylan delivers another performance cut from the same cloth.

This proved a remarkably fecund approach to the song. As Dylan performed it over the coming years, he did not depart from the post-Nara lyrical premise. Compare these four instances of the song’s opening:

Portland, Maine (April 10, 1997)

Ljubljana, Slovenia (April 28, 1999)

Cincinnati, Ohio (July 11, 2000)

Seattle, Washington (October 6, 2001)

One is struck immediately by both the consistency of the performances as regards key, tempo, and overall affect, as well as by the countless subtle differences between them, as Dylan finds ever-new nooks and crannies for variation in vocal timing, articulation, and ornament.

The Seattle performance is from less than a month after the September 11 attacks. This was Dylan’s second concert since that date, and the first to feature “Hard Rain.” It is a performance as remarkable for what it doesn’t do as what it does. There are no histrionics. Dylan does not overplay the song’s apocalyptic imagery or exaggerate the song-spanning build of tension, now standard from night to night. Instead, he offers a performance of restraint, comfort, and determination. At least, that is how it strikes my ears. Listen to verse 5 and see if you agree:

First note the fine work of Dylan’s guitarists, Larry Campbell and Charlie Sexton, who come up with a simple descending figure after the first answer, which they play first in unison, and then in parallel sixths. This bit of musical bridging material spans the space between Dylan’s lines, holding the listener secure in moments when the singing voice can’t. As for the sung lines, each one is different, and each saturated with telling details. Note, for example, the breath-catching pause that separates the initiating “s” from the rest of the word “speak” in “I’ll tell it and think it and speak it and breathe it.” The effect is like a musical stutter, stuck on the plosive, a blockage in speech at the very moment when the singer promises to “speak it.” One way to project determination is to project its obstacles.

One can also hear determination in “I’ll stand on the ocean until I start sinkin’,” which moves to a higher pitch. Tellingly, Dylan does not descend from this pitch on the word “sinkin’,” though musical convention would warrant a resolution one step down to a more stable pitch in the key. Dylan’s voice refuses to sink. Then there is the refrain. Here, as often in this particular performance of the song, “It’s a hard” sounds to me like “Yes, I know it’s hard.” We’re all struggling. Indeed, his third iteration in the final refrain seems to suggest as much: “I seen, it’s a hard!” The final iteration then includes a repetition rare in the refrain in any era—“It’s a hard rain…hard rain gonna fall”—the italicized words clinging to the performance’s ragged melodic apex.

It’s difficult to write objectively about such emotionally charged musical details, so I will not pretend to do so. I find this performance deeply moving. To these ears, that broken apex pitch is laced with grief, fear, resolve, and solidarity. Its affective multiplicity reminds me of a comment Dylan made to Studs Terkel thirty-eight years before this performance, in 1963. Terkel assumed “Hard Rain” referred to “atomic rain,” but Dylan quickly responded, “It’s not atomic rain, it’s just a hard rain… I just mean some sort of end that’s just gotta happen.” The young Dylan resists a univocal interpretation of his song, an over-literal limit on its meaning. The Seattle “Hard Rain” delivers on the song’s signifying multiplicity, its ability to sound not only comfort, or outrage, or determination, or fear, but all of them at once.

Adapted and excerpted from What Did You Hear? The Music of Bob Dylan by Steven Rings. © 2025 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

Fascinating. Need that book.

Oh wow. This is going to be such an important book! Thank you both.