How a Macy’s Stock Boy Taped Four Never-Heard 1960s Dylan Shows

Within a year Ray Andersen was a leading figure in the San Francisco counterculture

Flagging Down the Double E’s is an email newsletter exploring Bob Dylan concerts throughout history. Some installments are free, some are for paid subscribers only. Sign up here:

When I was in Tulsa over the summer, I spent a couple days poking around the Dylan Archives. Just before I arrived, archivist Mark Davidson clued me into a recent acquisition: Four never-heard live tapes from the mid-’60s.

As you can imagine, “never-heard live tapes” piqued my interest immediately. Two of the four shows have different tapes circulating (one taped by Allen Ginsberg, no less), though in worse audio quality than the new versions. But two of the four shows have never been heard before at all!

The four shows are:

February 22, 1964 - Berkeley Community Theatre, Berkeley, CA (w/ Joan Baez)

November 27, 1964 - Masonic Memorial Auditorium, San Francisco, CA (w/ Joan Baez)

April 3, 1965 - Berkeley Community Theatre, Berkeley, CA

December 11, 1965 - Masonic Memorial Auditorium, San Francisco, CA

I will go through what exactly is on each tape, and what I thought of them, in the next installments. But first, an introduction. These tapes, it turns out, come with a story. These were not tapes recorded officially by Dylan Inc. and just sitting in the vault for decades. Instead, these tapes were recorded by an unusual Dylan superfan in San Francisco. His name was Ray Andersen.

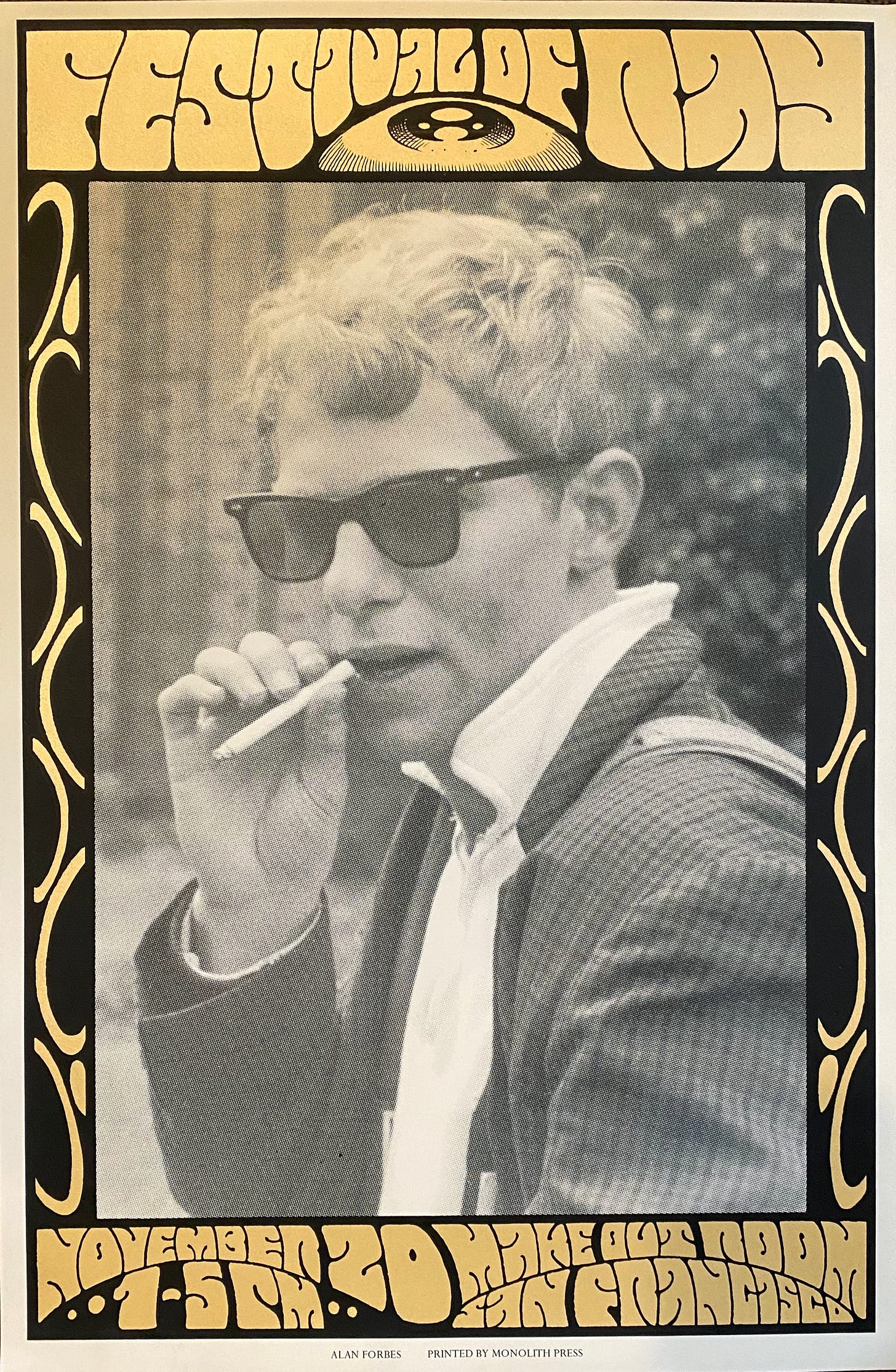

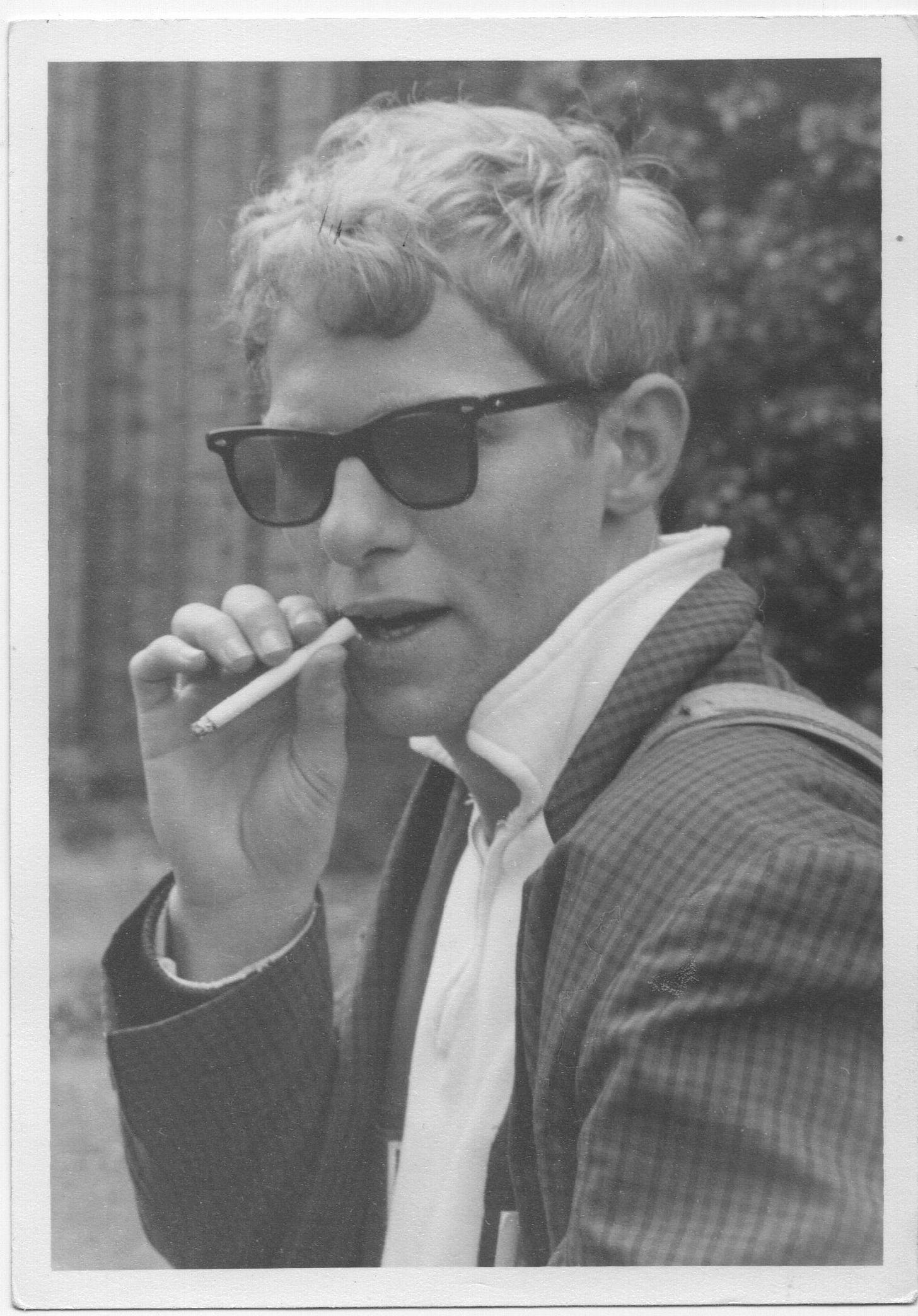

If you recognize the name, you know your history of the 1960s Bay Area counterculture. Andersen was a leading figure in the San Francisco rock scene, first managing the club The Matrix and then pioneering psychedelic lights shows at the Fillmore. Decades later he opened a record store, Grooves, that itself has a surprising Dylan connection. But in 1964, when he recorded his first live Dylan tapes, he hadn’t done any of that. He was a stock boy at Macy’s—and a huge Dylan fan.

Andersen passed away in 2016, but I spoke to his daughter Sunny Chanel. She manages his estate, which is full of rare music tapes and ephemera (some of which is available to buy here), and is responsible for getting these tapes to the Dylan Archives. She told me about her dad, and how she uncovered these tapes in the family basement.

Tell me about your father. How’d he come to tape these shows?

My dad was a music fan from a very young age. In the early sixties he was a huge Dylan fan. I’ll tell you about his life and then I’ll go back to the Dylan thing.

In the mid-sixties, he started doing psychedelic light shows. He did psychedelic light shows at the Fillmore for years with my mom. They were called Holy See Light Show. They did lights for Jimi Hendrix, Cream, Ike and Tina Turner. The list goes on and on. They were kind of at the forefront of the psychedelic light show.

He was also a huge record collector, and later opened a vinyl-only record store here in San Francisco called Grooves, which we still have open. But here’s the interesting thing. We had a customer come into Grooves. They said, “It’s so nice to be in here. I love the Dylan painting of Grooves.” And we’re like, “Wait, what?” “Yeah, I just was in Japan and there was an exhibit of Bob Dylan’s artwork.”

We hadn’t known this, but he did a painting of Grooves and Tops, this diner next door. There was a memorial poster after my dad died that we put in the window. Dylan included the memorial poster of my dad in the image. The gold square on the lower left, that’s an interpretation of the memorial poster that was there. That odd little honor for somebody who was such a big Dylan fan fifty years previously, like his essence is there, it was really wild to see.

Had he ever been to the store, as far as you know?

I have absolutely no idea. I actually asked Bob’s manager people, “Do you have any background on this painting?” They’re like, “No, but we’ll send you a print of it.” So they made a print just for us of the painting and had Bob sign it.

Is it displayed in the store?

No, we’re actually going to have it at the house, because if we had it displayed at the store, everybody would ask, “Is that for sale?” And we would have to keep on saying no. We just didn’t want to deal with it.

Before he started doing light shows, he was the manager of The Matrix. That’s where Big Brother and the Holding Company, Jefferson Airplane, Great Society, and all these bands got their start.

When he was at the Fillmore, he was flown to England to do the Carnival of Light, the sounds and the images, for Paul McCartney’s event. It was a three hundred and sixty degree light experience at the Roundhouse with this experimental music that Paul did. He stayed with Paul for a week.

“Carnival of Light” is the legendary never-heard Beatles piece. I’m surprised no one bootlegged it if it was actually being played in public at this thing

People weren’t tape-recording things as much. Except for my dad, he taped everything. Before it was a thing to do, he would bring this big bulky recording device to concerts. And that’s how he did the Dylan tapes. It was just him going to the shows here in San Francisco and the ones in Berkeley with this bulky recorder and recording the concerts.

So he’s just setting this big device on a table or on the floor or something?

On his lap. For example the Matrix, he recorded all the bands that would come. We took that archive and this record company, High Moon, they acquired the Matrix tapes from us. They’re putting out a bunch of releases from his tapes.

Who are some of the artists that we would know?

Great Society. Sopwith Camel. A lot of Grateful Dead. They just did a record of Jeannie Piersol, a female vocalist who was a good friend of my parents. Lightnin’ Hopkins, some other blues guys. It’s a hundred tapes.

New transfer of a 1968 film directed by Ray Andersen:

Then he was good friends with Lenny Bruce, so he would record all of his and Lenny Bruce’s phone calls. So I have this bizarre archive of Lenny Bruce phone calls. He was just really into taping and archiving.

I was just going through his stuff, all these tons and tons of tapes, and I’m like, “What are these?” It said “Bob Dylan” with his handwriting and the dates. I did a little search online and I’m like, huh, these shows don’t seem to exist.

You say you were going through his archive. Where were these sitting for sixty years?

In boxes in the basement. That’s my full-time job now, going through all this stuff and finding where to put it all. Getting things into the right hands. He had hundreds of lunch boxes, thousands of rock posters. We inherited the record store, so a gazillion records. The kitchen was filled with boxes of records; you couldn’t even hardly walk through it. The dining room, the living room, just boxes of books and records. He was a book dealer as well, so we have thousands and thousands of books. And just esoteric weird little things, like postcards, rubber stamps, sci-fi books, robot toys. He collected everything.

It’s finding treasure. Finding those Dylan tapes was such a neat little thing. So these tapes going to the Bob Dylan Center was perfect.

Did you listen to them yourself? What did you think?

I really was struck by the banter in between songs. Having the audience laughing, like a little stand up routine. I was really surprised because I always think of Dylan as more serious. That levity at the one in Berkeley. How casual it felt. It didn’t feel like a lot of pomp and circumstance.

It’s funny you mentioned that just because I was looking at the notes I took in the archives. One of the first phrases I wrote down is “tons of audience laughter.”

You never think of a Bob Dylan concert and him cracking people up.

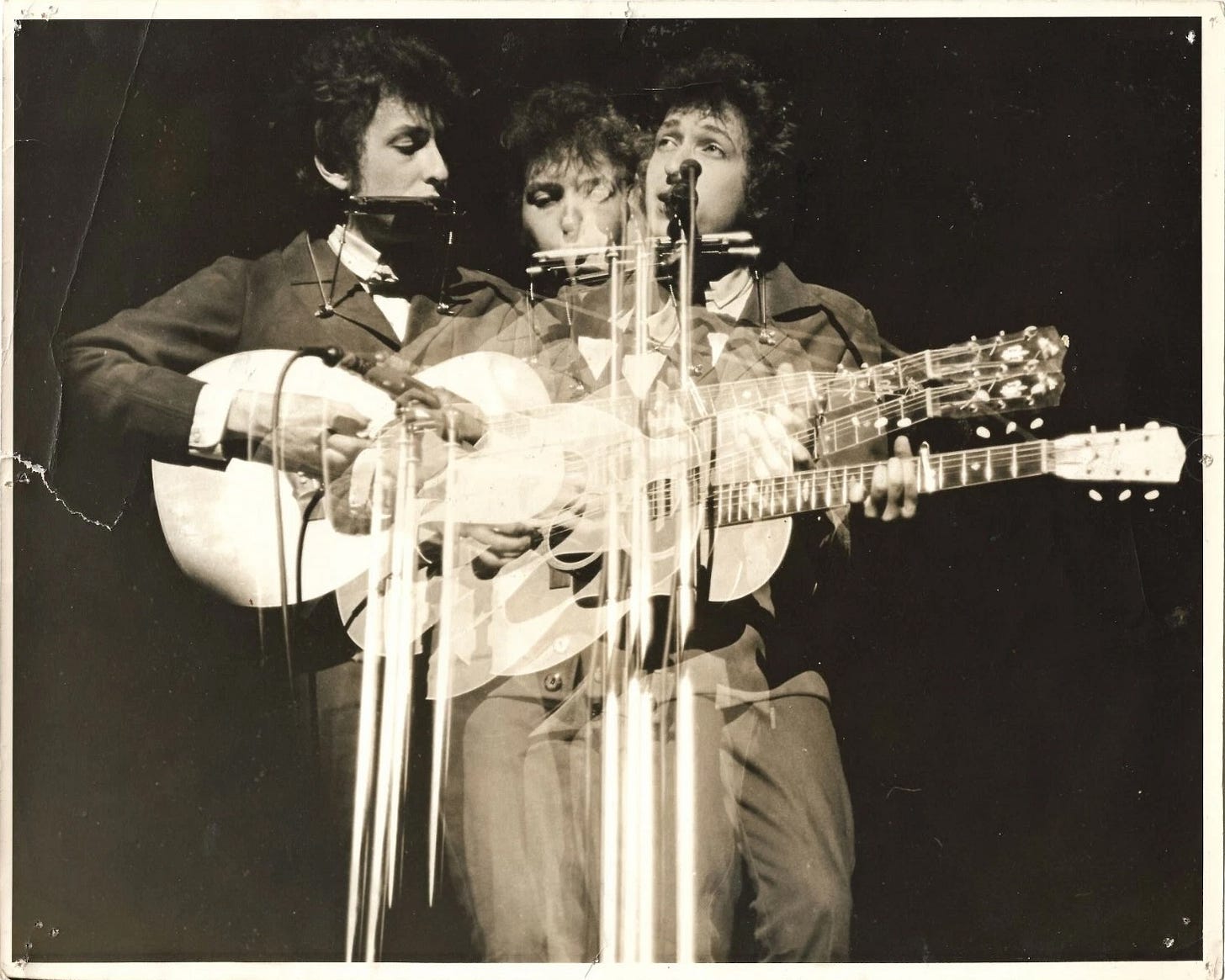

These four tapes capture such an interesting window. It’s ’64, ’65 so it’s like the transition they just made an entire movie about. A couple with Joan, and then by the end he’s electric, just in the year and change your dad captured.

I’m so thankful that my dad taped it, and I’m so glad I went to the Center. It was like, “What am I going to do with them?”

How long was he doing this taping? Was this a few years in the sixties and then he stopped?

The sixties, that’s it. There was that moment in time where he had his trusty tape recorder and recorded everything. And then the light show kind of took over. That was his new hobby.

So was he doing the light shows in ’64 when he taped the first stuff?

No, that was like ’66, I think he started doing that.

How about The Matrix? Would he have been working there?

I think that opened in ’65.

So what would he have been up to in 1964 when he taped this stuff?

I think in 1964, he was not really involved in anything yet. I think he was working at Macy’s. He was a stock boy at Macy’s for a bit.

This one year, Dylan has this huge transition, and it sounds like your dad does, too. From a Macy’s stock boy to in the counter-culture music biz.

Yep. He just got the Matrix gig from a friend of his who owned the club.

At this point, how much stuff are you still sitting on trying to offload?

There’s a lot of tapes I still need to listen to, ‘cause I don’t know what’s on them. My dad’s handwriting wasn’t very good. There’s a lot of cryptic handwriting. The Lenny Bruce stuff, we’re looking to hopefully get that into the right hands.

You think there might be more Dylan in that cryptic handwriting?

I doubt it. The Dylan things were grouped together. A lot of things, I kind of knew, this is the collection of that. Like, this is all the Matrix tapes. These are the Acid Tests. He also taped those. There’s some crazy tapes of Neil Cassidy going on these like weird tangents, all the Merry Pranksters. Another snippet of time.

You said he got a lot of Dead stuff too, and it must have been very early Dead stuff.

One of the things that we have is the earliest Grateful Dead footage ever to be recorded.

What’s going to happen to that?

I don’t know. I was talking to somebody about it being used in a movie. Some of my dad’s other footage that he took of the Dead recording Aoxomoxoa has been used in some documentaries. It’s him in the studio with the Dead and Owsley and they’re all doing nitrous. It’s a crazy tape.

He did some video stuff. He directed two Creedence Clearwater Revival videos that we end up selling to their management company. We found all the original footage. He was all over the map. But I like finding these things. I feel like it’s my calling now. I just have to make sure everything gets to the right place.

Did he meet Dylan back then?

He never had any interactions with Bob Dylan at all. Of the musicians he really admired, he met everybody else. So it’s interesting that he never met Dylan, but still that painting of Grooves, having that touchpoint is poetic and beautiful. That his store was honored in that way by somebody who he admired so much.

Thanks Sunny! Bonus thanks to Mark at the Archives, and to Scott Warmuth for providing info on the painting. In a few days, I’ll send out the second installment, where I go into detail about what I heard on these four never-circulated live Dylan tapes. UPDATE: It’s here.

Personally this was a fantastic article for me to read. I am old school lightshow person and the first lightshows I ever saw were at the Fillmore in San Francisco in the summer of 1966. It must have been Ray Anderson , or now I'd like to think so! Me and my lightshow tribe went on to travel the world with rock bands for 5 years. And the way Ray connects to Bob, it's just gives me goosebumps! We're about to fly to Paris and then on to Amsterdam to see Bob. How lucky can one old hippie get?

The fantastic deep-dive investigation that you have made your signature. What a great read. I must admit to some frustration that this kind of thing (and no doubt a lot more) is tucked away at Tulsa ... and only available to "researchers" ... but I'll take this as a great substitute until Amazon delivers my pitchfork.