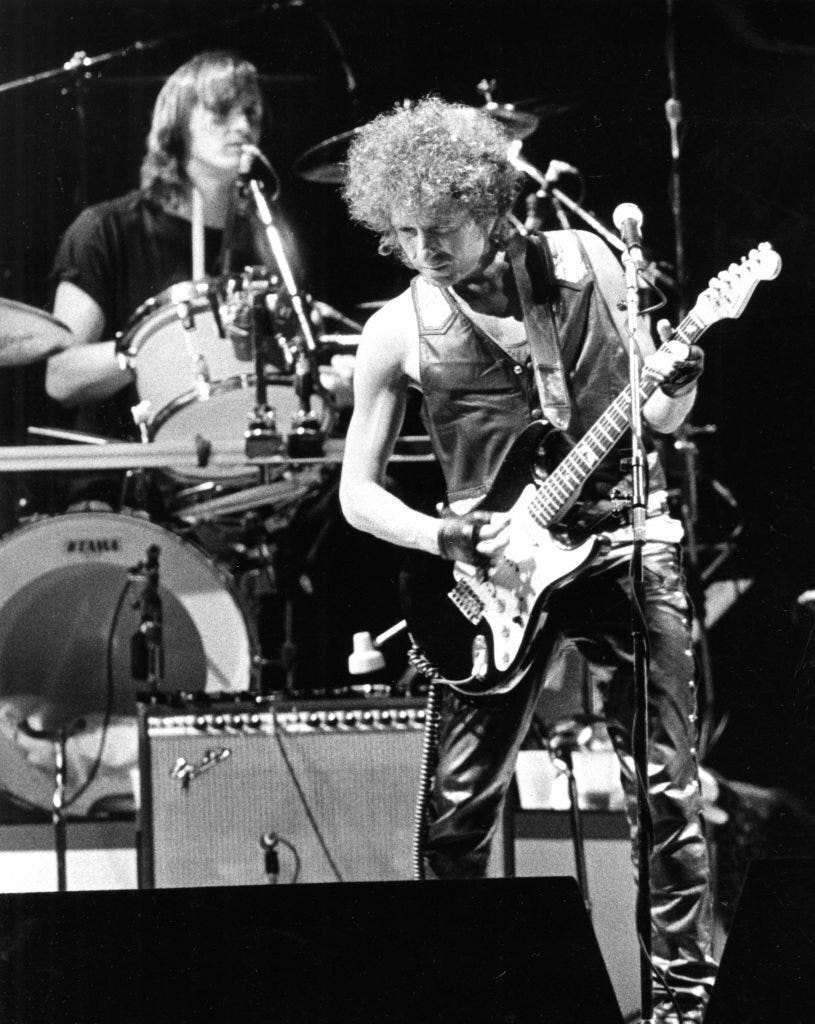

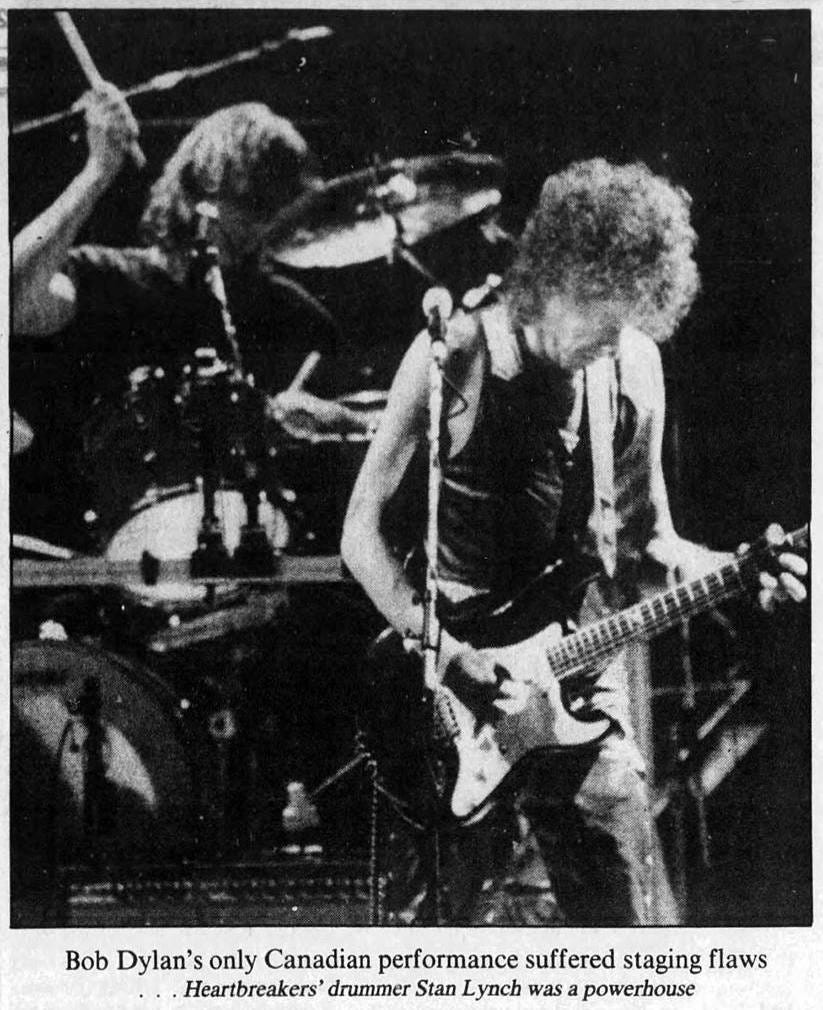

Heartbreakers Drummer Stan Lynch Talks Touring with Bob Dylan in the '80s

1986-06-09, Sports Arena, San Diego, CA

Flagging Down the Double E’s is an email newsletter exploring Bob Dylan concerts throughout history. Some installments are free, some for paid subscribers only. Sign up here:

Update June 2023: This interview us included along with 40+ others in my new book ‘Pledging My Time: Conversations with Bob Dylan Band Members.’ Buy it now in hardcover, paperback, or ebook!

To celebrate February’s anniversary of the first date of the first tour Bob Dylan did backed by Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, I ran an interview with Heartbreakers keyboardist Benmont Tench. And today, on the anniversary of the first date of their second tour together, I am happy to present an in-depth conversation with the band’s drummer, Stan Lynch.

Dylan hired the Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers to back him for much of 1986 and then, following a few summer dates with the Dead, 1987 too. He later wrote in Chronicles, “Tom was at the top of his game and I was at the bottom of mine.” But Stan disagrees with the second half of that statement — and I do too. Those ‘86 shows in particular are about as fun as it gets, a joyful mix of hits and deep cuts and old-time-rock-and-roll covers, all backed by as a whitehot band as well as the Queens of Rhythm backing singers. As I’ve written before, it’s a personal favorite era of mine, and I was thrilled to talk with someone else who was on that stage.

To avoid too much overlap, I tried to ask Stan different things than I did Benmont. And, as Stan says, he brings a pretty different perspective than his longtime bandmate. He notes at one point, “I would love one day to be interviewed en masse and go around the room. Because then you'd get the truth. It takes everybody there to give you the truth. I don't know the truth. I just know what I think I saw.”

So when you’re done with this, read my equally long conversation with Benmont Tench, if you haven’t already, to get another perspective (and then, for a third take, my interview with former Petty and Dylan road manager Richard Fernandez). But, right now, here’s my conversation with Stan Lynch:

When I first emailed you, you said your experience was totally different from Benmont’s. Was there anything specific you were referring to?

There was a lot of pain in Ben's interview for me. That's how five guys can be such good friends and never know each other. Ben was very private, and I didn't realize he was struggling and how much personal pain he was going through.

I wasn't experiencing any of that. It was joy. The whole time, I was flying. My life was great, my body had never been stronger, no one ever to told me what to do or what not to do.

There was never a playbook. My joke was, I'm going to count four and then Bob is going to just start playing and, in about a minute or so, we'll know what song it is. It was glorious. I found the whole thing close to jazz. The front man is John Coltrane. I felt like Philly Joe Jones in those three hours. Everybody was just masters of improv.

Do you play?

Some guitar.

Do you know when you're having the best jam session of your life? One of those where you just go, "My God, I don't know where we're going, but this is really cool." It was like getting to jam, but the skeleton of the jam was “Like a Rolling Stone”! As long as you stick to the intentionality of that song, and you stick to the passion of the lyric, there was nothing you could do wrong from the drummer's seat. I just listened to Bob and did what he did. It was like serve and volley, punch and counterpunch. It was aggressive and exciting when it needed to be; it was beautiful when it needed to be.

The only time I knew I'd stepped out of line—there’s a great scene in Hard to Handle when I think I’m supposed to kick in, so I play this big drum fill announcing the band. And Bob just simply puts his hand up behind his back, without stopping the harmonica, and just shows me his palm. Which says to me, "Not now, kiddo. Back off. Save your rattlesnake bite for a later moment."

We'd probably done it a million times the other way, but I loved that you couldn't close your eyes and do anything by rote, ever. I found that to be so exhilarating. I never slept better in my life, because you were on your toes physically, emotionally. It was almost sensory overload to play with Bob.

Did you feel prepared for that, from your work either with The Heartbreakers or elsewhere?

Chaos is my middle name. I was born for anarchy and it's like, that's Bob! He's just a natural at it.

We're playing a big gig [one night]. I think three songs into it, Bob turns to me he says, ''Hey, Stan, what do you want to play tonight?" I'm thinking, "Uh, loaded question?" But I took it right at face value and, I went, "Well, how about ‘Lay Lady Lay’?” Because we'd never done it. I wanted to do that cool beat that's on the record, that beautiful mandolin swing. It just feels like mandolins are bashing into the wall. I really wanted to try that rhythm live.

That's how fearless you are. It didn't even occur to me that that might not be a good idea [to pick a song we’d never played before]. He says, "What key?" You never ask a drummer what key! I see Mike [Campbell] in the corner going, "A! A! A!" I go, "How about A?" Everybody has a big sigh of relief. Then Bob walks up to the microphone and proceeds to play a song I can't even recognize. Like, if this is “Lay Lady Lay,” I have no fucking idea, but it was fun as shit. It was the Ramones doing “Lay Lady Lay.”

The band was a little horrified maybe, but I was only horrified for about a second. I realized, "Well, we're really going with this!” We went with four minutes of “Lay Lady Lay” as a punk song, replete with the Queens of Rhythm all trying to find their way in. It was fantastic, but it was absolute anarchy.

Obviously by that point, you've got quite a comfort level together, but let's rewind back to Farm Aid 1985. First time in the room together rehearsing, what does that look like?

Fantastic. Interesting story, I think it was the first rehearsal. We were supposed to start at two and Bob showed up at five maybe. I already had tickets to see Frank Sinatra and Sammy Davis at the Greek. I'm a big fan. I remember saying around six o'clock, "I got to go." I just figured, fuck it.

Bob walked right up to me. He said, "Where are you going?” Like, what the fuck’s wrong with you? I said, "I got to go see Frank and Sammy."

The whole band backed away from me as if I had radioactive dust coming out of my ass. Bob took a big beat, and, God as my witness, he said, "Frank Sinatra? Sammy Davis? I love those guys!" So I took Bob as my date to go see Frank and Sammy.

What was your date like?

I was scared shitless. Like, he's in my car. Do I turn on the radio? What if Bob Dylan comes on? I think we just sat in silence.

We went to the Greek. Bob had the hooded sweatshirt on. Nobody really knows [he’s there]. I did somewhere between buddy and security, and we watched the show.

I think Sammy came out first, and it was fun as hell. I was probably stoned and just digging the show. Sammy ended and everybody stood up. Bob went to leave. He thought the show was over. I grabbed him by the back of the sweatshirt and went, "No, Frank's next!" "Oh, right."

I remember during intermission thinking to myself, "Gosh, I guess we should talk. That's what guys do.” And so we talked. He's just a guy. I figured, “Well, guys like to talk about motorcycles and girls.” So we did.

Then Frank came out. I'm watching Frank, and I'm watching Bob watching Frank. I'm just going, "Wow, this is a Fellini moment." We make it through the whole show, and somebody backstage figures out it's Bob. Somebody comes out and goes, "Frank says come by the dressing room after the show and say hello." I'm thinking, "Fuck, yes, this is going to be great!" I had a long-term love affair with the Rat Pack my whole life. It's been a thing for me.

So we go by the dressing room. I go, "Bob, over here. Let's go in and say hi to Frank." He goes, "Nah. Let's go."

So close.

It was so perfectly Bob. Like, "Nah, fuck it. I'm outta here." [laughs]

Love it.

Every time he was in the room, there was this energy. Talk about a guy who can read the room all wrong, that's me, but what I read was Bob was ready to have fun, play some music, don't stress, no posturing. Can we just make a joyful noise unto the lord? Every time he turned around, he would rock with me. If I was catching a groove, Bob did all the things that you want your frontman to do. Hips are swaying, shoulders are moving, he's looking at you and he's pointing. I loved every inch of it.

Did that come from day one, the band and him gelling like that?

Yes. I felt energy from him and freedom from him like I couldn’t even imagine.

The only fear I had was, I didn't want to disappoint Bob Dylan. I don't want to play something that he just thinks is offensive. But I figured he'd tell me. He was just that kind of guy. He'd walk up to you and go, "That’s a pile of dog shit." Fortunately, I never heard it. Matter of fact, I actually got some really nice “atta boy”s from him, that really, I didn't get that often.

Like what?

I remember one day he walked up right to the drum riser. I thought, "Oh, shit, I'm about to get it now. This is the moment I'm fired." I think all he said was, "Man, you're playing great right now. I love this." Part of me was wondering, "Is this a joke?” Maybe that's his way of saying you suck so hard I can't believe it. I figured I might get the call the next day from Elliot [Roberts, manager] and he'd say, "Hey, Bob thinks you suck.” I never got that call.

I loved what he did to the chemistry to the band. It just changed the dynamic. You add a sixth member on anything— oh, and that other guy is Bob? Like, "Well, this is dynamite in the baby carriage right here. Carry it carefully." We were all very reverent. I saw it immediately in the other guys too. It was like, "Oh, shit, we're in the presence of somebody who can really do this!" We thought we were seasoned vets, and we realized, "This had been pre-cooked way before us. He's been good a long, long, long time."

What do you remember about that first actual show, the Farm Aid one months before the tour?

I don't remember much except I think we did “Maggie's Farm.” It was funny as shit, because none of us really knew what was going to happen.

I think Willie Nelson came out for that too.

I was probably shitting my pants. I was probably going, "Wow, this is a Wayne's World moment for me. I'm playing with Bob Dylan and Willie Nelson and Tom Petty and The Heartbreakers!" You just go, "Pinch me. This is the kind of shit I dream about, and it's happening." I was pretty much in that mode for my entire rock career. I never could believe it. I was just going, "Holy shit!"

I found him to be very likable. I hope you can convey in this interview the big grin on my face when I think of Bob Dylan. That's why I said Ben and I had very different memories. I was experiencing zero pain — physically, emotionally, spiritually. I was only experiencing joy. I'm getting to play amazing songs with amazing musicians in amazing places all over the freaking world. It wasn't like, “Oh, yeah, you're playing Spank, Idaho." You're going to go to New Zealand, you're going to go to Australia, you’ll be playing in East Berlin and all over Italy. It’s like, "Oh, fuck!" He's universal. Bob speaks the universal language of brilliance.

You mentioned Australia. One of the things you did there was record the first Heartbreakers/Dylan song, “Band of the Hand.” Do you remember anything about that?

It was quick. I think we learned it in the studio. You can hear me trying way too hard, because I'm still in live mode. I'm like, "I'm not making a record, I'm making a live document of our aggressive fabulousness.” I probably came in, beat the shit out of my drums for a couple of hours, and they said, "Get outta here." [laughs]

You’ve got The Queens of Rhythm singing backup too. Dylan had been doing stuff like that in the gospel years, but was that new for you and The Heartbreakers?

I'd never experienced anything of that caliber. They were fabulous. They also played rhythm, tambourines and shakers. They were bringing the church to this shit.

What a show for me, because I got the best seat in the house. I'm looking to my left and there's those wonderful women just physically involved with the music. I look to my right and it's Benmont and [Heartbreakers guitarist] Mike Campbell, and I looked to the front and it's Bob Dylan and Tom Petty. It's like, shit, everywhere I look, it's great.

What does it look like when you're not on stage? Are people hanging out together during the off-hours or keeping to themselves?

The camps were pretty established. There were nights in the bar you'd see everybody. You never knew who would be there. The people that Bob attracted, and the people that were coming to me with stories about, “Oh, I was Bob's masseuse. You have to tell Bob that Joe said—." I'm getting like five of those an hour.

There was one show we did where it finally hit me. I wasn't the sharpest tool in the shed with music back then. I was very self-absorbed, as many young musicians are. Then when we were in Italy one night, I remember I really heard Bob Dylan. I heard him.

Usually when he did his solo stuff, I was like, "Well, if I'm not involved, I'll leave." But I was sitting there at the drums still. I sat behind the kit and I smoked a cigarette and I watched this man. It's one guy, one guitar, and he's singing “Blowin' in the Wind.” I melted. I cried. I started to actually weep because it hit me in that one moment finally. Like, this guy wrote all this stuff and he’s doing it tonight. It's pouring out of him like sweat. It feels effortless, but it's killing me. Every line ripped me to shreds. He did a song, I wish I could remember it. It was about a young man who volunteers to go to war and he comes home with the medals.

“John Brown”

Yes. He puts the medal in her hands. Just thinking about it now can choke me up. That was the moment I was never the same on the tour again. I was never the same. I remember walking up to Bob at the end of that show while we were all still sweaty. I put my hands on his shoulders and said something like, "You really fucked me up tonight." He looked at me with that billion-dollar look and he said, in that voice, "Stan…are you all right?" Like he didn't understand what I was saying to him. What should have come out of my mouth was nothing, but, of course, being me, I had to say something. What came out of his was like, "No, no, not you!"

It was strange. I don't know if the relationship— I'm not saying we had a relationship, but I looked forward to seeing Bob. I loved talking to him. Everything you say to him, whatever came back was not what you expected. I remember once saying something like, "Wow, I love that outfit." He said, "Yeah, what do you like about it?" It wasn't what I expected. You’d expect like "Thanks man" or whatever.

Bob was fantastic at keeping you on your left foot all the time. I did not find that uncomfortable, I found it growth-inspiring, exotic, enticing. Challenging, in a good way. Like, "Bring it."

Did you have any favorite songs to play, either ones you did every night or something you did once or twice?

“Positively 4th Street” used to blow my mind. “Like a Rolling Stone” blew my mind. “Knockin' on Heaven's Door” blew my mind. I'd have to look at the song list because probably every freaking song I go, "What??" For me it was hard not to just be excited to be there every second. How amazing to know that I'm going to play three hours of songs that are etched in my soul. At one point Roger McGuinn comes up and sings “Mr. Tambourine Man” in front of hundreds of thousands of people in East Berlin. The place looks like a sea that's going to erupt. Even at the time, “This is going to be an apex moment. This is a zenith.” I felt it. “From here on out, it's going to be a letdown.”

I miss it. If there was ever a part of my life I could relive, that might be it. The rest of it, I'm cool. I'm glad I did it. That's one I would like to do again.

You did some shows with the Grateful Dead, big stadium shows in the US. Do you remember anything about touring with those guys?

Once again, I had a completely opposite experience as Ben. I was not a fan, so I didn't care. The guy you're talking to now knows what a stupid thing that is to say. The man you're talking to now, 30 plus years later, knows what an idiot that kid was.

You didn't know me then, but I was more of a hedonist. I was like, "I'm in a rock and roll band and all of that implies. Take no prisoners. I want it all." That was me. I was not really a session guy or a guy that wanted to be taken lightly or not noticed. I had a big mouth and I played a lot of drum fills and probably made way too much noise coming out of my mouth and my drums. Fortunately, everyone was tolerant.

To me, what's so special about these tours, and I think I said this to Benmont, it's like the most pure fun you can hear at a Dylan show. Even the great Dylan shows, sometimes “fun” isn't the key word. A big part of that is you driving it forward, hard and loud and having a blast. I think it comes across even if you're just listening to a bootleg.

I played those gigs as ferocious as I was capable of. Most drummers will tell you, "Never go to 10." If you go to 10, you blew your wad. But I did. I went all the way. Benmont went with me too. Everybody did. Everybody was fully willing to engage. When it was time to throttle up, it was all the way.

You mentioned McGuinn. I was looking through the setlists, you had so many people sitting in. Stevie Nicks, Mark Knopfler, John Lee Hooker, Ron Wood, Harrison. Any good stories about anyone else?

Where was John Lee Hooker? Was that in San Francisco, with Al Kooper there too?

Yeah

It's a story. It's not a good story. Maybe I'll hold onto that one. That was a bad night for Tom and I. Tom and I had a very, very bad night. We argued terribly. John Lee Hooker and Al Kooper came out and saved us from being assholes. That's about as nice as I can put it.

The presence of outsiders got you back on your best behavior?

Actually, it was probably a turning point for Tom and I. We never recovered from it, but the evening was saved by the presence of greatness. I love Al Kooper. He's essential. He's just essential in so many careers, including mine. He's a loadstone and he doesn't even know it.

It's funny you mention him, because Ben told me that he knew the Al Kooper parts on stuff like “Like A Rolling Stone” and was playing off of those. Did you have an equivalent? Were you thinking about the “Positively 4th Street” drum part or Sam Lay or—?

No. That's what's so pathetic! That shows you the absolute arrogance and profound stupidity. It wasn't until after the tour that I started hearing what the records really were like. I don't think there's one thing I ever did with Bob Dylan that was ever from the record, except maybe…let me think… No, I fucked up everything. [laughs]

I had no clue what anybody did. Never studied a record in my life. I probably actually thought that's what the record sounded like. I'm not sure if idiot is the word. Ill-informed. The fact that that guy was tolerated is extraordinary.

Obviously you knew the hits at least. Did you know the deeper cuts?

No, I didn’t. I owned a few Bob Dylan records. I loved them, but I never studied them. All I knew was, I loved the way he sounds. When everybody would tell me like, "Bob Dylan can't sing," I'm going, "No, he sounds cool as shit." I loved the way he looked, I loved what he wore, I loved his record covers.

He was a cult figure to me that you could never know, so I didn't really bother trying. I didn't really think about his life, or the depth of it. I was young and dumb, man. A rock and roll fan. I loved what I loved and Bob was part of it. I loved Steppenwolf too. I was more like, "I wonder what kind of chicks Bob gets. I wonder what he drives."

I've got a few couple specific shows in the later stages of your two-year run to ask you about. One was the opening of your final tour in Israel. It was a big deal at the time, him playing there. What do you remember about that?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Flagging Down the Double E's to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.