Dylan's Forgotten Gaslight Gig

1963-03-31 (?), Gaslight Cafe, New York, NY

Today’s newsletter is a guest entry from Adam Selzer. Adam’s popped up here a couple times, writing about shows in 1984, 1999, and 2001, but today he goes way further back to explore a forgotten 1963 Gaslight Café show he found buried in the Village Voice archives. Over to Adam…

It’s strange, but finding a Dylan setlist from a long-lost gig in 1963 seems like it would be infinitely harder than finding one from, say, 1974. It seems as though ’63 was a whole lot further in the past. Maybe it always did; when American Graffiti came out plenty of critics noted that 1962 seemed like far, far longer than twelve years ago. And the same is true for me, even though I wasn’t there in ‘62 or ‘74 at all. Sometimes history gets weird like that.

Twenty years or so ago, I bought a Blind Willie McTell CD that reproduced the liner notes from a vinyl edition that had come out in the ‘60s or ‘70s. In it, that gave a brief biography of McTell, then noted that they weren’t really sure, but it “seemed likely” that he was now dead.

I found it terribly amusing that they’d put out an album without knowing if the artist was dead or not. I also enjoyed knowing what they didn’t: that he’d passed away in the late ‘50s. At the time, I was delivering pizza in Milledgeville, Georgia, and the hospital where he’d breathed his last was part of my route. Now and then someone at the hospital would put in an order without giving a phone number or specifying which building they were in, which led to some adventures in a grim complex of cheerless, largely abandoned buildings once known as the Georgia Lunatic Asylum. The place seemed like a relic from another time – from the “Old, Weird America.” Only it was still here.

When those liner notes were written, guys like McTell and all the people on the Anthology of American Folk Music probably seemed like they came from another century, and I’ve heard it said that most of the people hanging around the Folklore Center in the early 1960s never stopped to think that any of them, let alone most of them, might still be alive.

The same can seem true to me of those people from the old Greenwich Village folk world. I may have seen Dylan dozens of times, and others from those days a handful, but sometimes it seems like a jolt to me to think how many are still around. They’re not even really that old. I meet and hang out with people from the fringes of that world now and then. But even when they tell me their stories, it can still seem like a whole other world from the distant past, all trace of which should have vanished by now (And, yes, I imagine my teenage stepson feels the same when I talk about the 80s, even though he listens to hair bands all the time).

I spend a lot of time dwelling in the past – as a tour guide and historian, I do a great deal of work in the microfilm room at the library. Plenty of old papers are digitized now, but if I’m researching some old Chicago story, I could miss out on something critical if I don’t also check the Chicago American, the Democrat, the Post, the Press, the Journal, the Times, the Record-Herald, the Chronicle or the Mail. And scrolling through those reels is like time traveling. As the pages scroll by, you immerse yourself in lost society. You see who was appearing in the night clubs, what movies were playing in long-lost theaters, scandals that never became movies, and all the other ephemera that makes the world in the background of the big news.

One day, after looking up whatever antique murderer I was covering that day, I noticed that the filing cabinets contained a couple of reels of The Village Voice from the early ‘60s and decided to give them a look, just for fun. The articles were surprisingly dull – mostly neighborhood politics and drama that now seem as distant and unimportant as the high society blatherings that fill the society columns of Gilded Age papers.

But the ads were something else. The sheer number of great artists you could see at any given time in the Village in those days was astounding. On one night alone, the Café Wha? featured Josh White, Shel Silverstein, and Judy Henske. The same night, you could see Zoot Sims at the Half Note. Over the course of a few weeks, there were ads for Ramblin’ Jack Elliot at the Gaslight with Dave Van Ronk, Nina Simone at Carnegie Hall, Dylan at Town Hall, Rev. Gary Davis at Folk City, Barbara Streisand and Phyllis Diller at the Blue Angel. On various nights the Village Gate had Stan Getz, Lightnin’ Hopkins, John Coltrane, and/or the Modern Jazz Quartet.

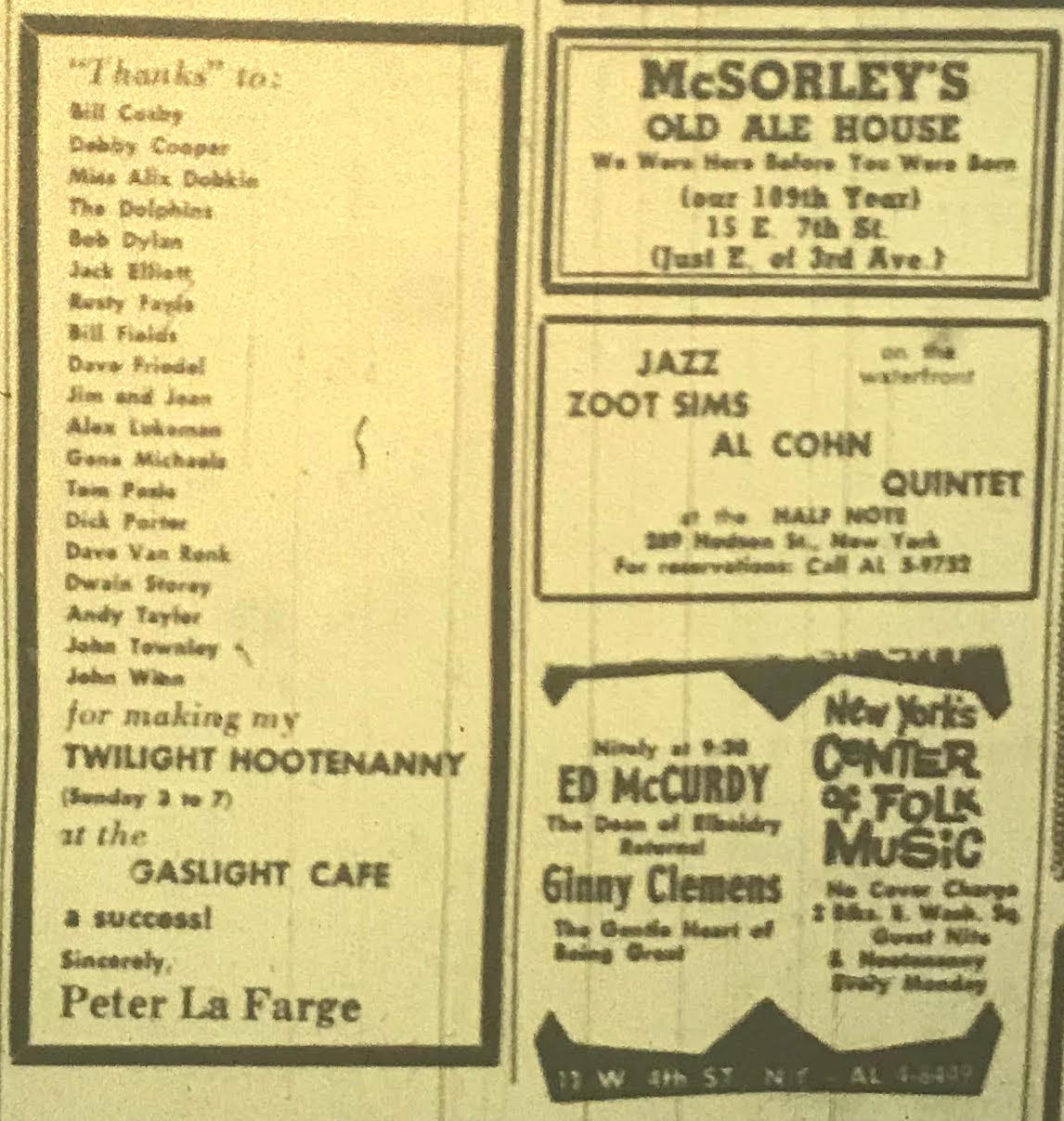

One particular ad caught my eye – an all-text posting from early April, 1963:

Dylan at the Gaslight in 1963? Like most Dylan completists, I’ve had the “Gaslight Tapes” from 1961 and 1962 for years, and spent considerable effort trying to figure out the correct order and which songs were from which night, but I’d never heard of him playing there in 1963.

I hustled home and started checking all the usual sources – Olof’s Files didn’t list any Dylan appearances at the Gaslight that year. Peter Stone Brown had never heard about it. The closest I could find to what Dylan was doing at the time (based on the reference to “Sunday,” it would have been March 31) was an appearance on Bob Fass’s radio show a few days earlier. Two weeks later he’d play his concert at Town Hall, and shortly thereafter would resume recording Freewheelin’. The month before, he’d posed for the iconic cover photo. But the day-to-day details of late March, a hugely important period in his development as an artist, a writer, and a star, were largely blank.

Had I found a Dylan Gaslight appearance from 1963 that everyone had forgotten?

That Dylan played at the Gaslight at other times than what we have on the tapes is a given; that he was still playing there later than is generally assumed is entirely possible. In the latest issue of Mojo, John Sebastian talks about being stunned when Bob premiered “Chimes of Freedom” there one night, which would have probably been several months after this “Twilight Hoot,” (though I suspect that Sebastian meant to say “A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall.”)

So, with no tapes, and no published reports, the only thing to do was try to track down the people who’d been there.

Naturally, I wasn’t going to be able to ask Dylan himself - or Bill Cosby - about that night in Spring of 63. But many of the people on Peter La Farge’s thank-you list had easy-to-find contact info. A few even responded.

I suppose it’s a measure of just how much was going on in the Village at the time that you could get a lineup like that in the same room and no one would think it was notable enough that it would stick in their memory, but no one recalled much about it. John Townley wrote, “I don’t remember that day, except I do faintly recall Peter trying to organize it as an opportunity to expand the Gaslight’s hours but basically an attempt to promote himself.” That was as close as anyone came to ringing a bell for anyone. “There were a lot of events then,” said Alix Dobkin. “63 was a good year. Hoots of one kind or another were popular and common.”

Most of what I heard back was juicy gossip about the Village folk scene circa March of 63. No one took the opportunity to say anything call Dylan a toad or anything, but other names on the list seemed to inspire passions even after all these years.

“Gene Michaels,” said one respondent, “was a Dylan would-be, but devolved into drugs (and) moved up to RI to work in a shoe factory… he remains in my memory with his perfect mainlining quote, ‘There is no problem a good solution cannot cure.”

Most of the dirt was about Pete La Farge himself, about whom opinions differed. Some called him “a good friend” or “the real deal,” others called him “spoiled” “narcissistic,” and “A Josh White imitator.” His daily drug intake was apparently so impressive as to still amaze people sixty years on (he died in October, 1965 of a Thorazine overdose).

Dwain Storey I actually knew slightly; he hung around at the same bar in Chicago that I did – the Gallery Cabaret - which had a number of regulars with stories of Greenwich Village in the 60s and 70s, and even a few O.G. beatniks now and then, though I think the last of the resident beats passed away a couple of years ago. Unfortunately, when I found the ad Dwain had recently moved into a nursing home, and passed away before I managed to connect with him.

But even if I’d spoken to him, I doubt he would have remembered that night any better than anyone else seemed to.

So, what happened that evening at the Gaslight? Did the people on the list get up and perform, or was La Farge just giving a shout-out to everyone who swung by to say hello, whether they actually got onstage or not? The latter is probably more likely. However, it’s not impossible that Dylan played a bit, maybe trying out one of the many new songs he was working on at the time.

It’s still in the realm of possibility that someone out there will remember that night in more detail, but in all likelihood it’s one those old events that are now lost to history, leaving not even a setlist in its wake. If La Farge hadn’t been so determined to promote himself, there might be no trace at all. That probably couldn’t happen today – with that many known people in the room, we’d probably have tweets and videos. Pete La Farge would have been sharing clips like crazy.

And I wish we did have things like that. I wish there was a collection of selfies people took that night, and some recordings. But it’s also nice to know that, even though ’63 wasn’t as long ago as it might seem, it really was another era, and that some parts of the past get the privilege of remaining a mystery.

An author and historian, Adam Selzer has been hosting virtual tours of Chicago for the last year; his next book is about Chicago’s Graceland Cemetery. Find out more about his work, and the free daily “mini tours," at mysteriouschicago.com.

Interesting stuff, thanks. This is one of those times and places I am sad to have missed.

Great article - thanks